Beyond capturing the ultra stylish hipness of his post-colonial cohorts, Sidibé joyfully affirms the lives, identities and aspirations of a generation reaching for freedom and asserting their modernity into the world. Beyond that, his photographic images have become part of a visual lexicon that resonates and extends to communities worldwide.

Eve Sandler on the late Malick Sidibé.

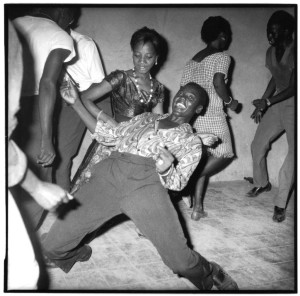

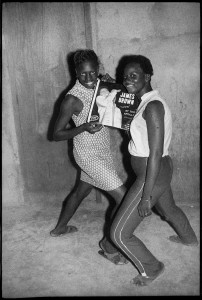

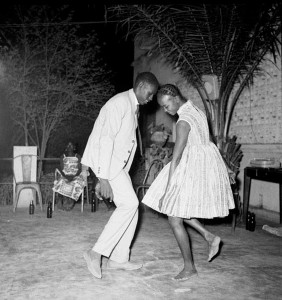

Nuit de Noël, 1963.

Malick Sidibé: The Transformative Gaze

With the passing of Malick Sidibé last month at 80 years of age, Mali has lost a native son and national treasure. The world has lost a seminal artist, one of the great photographers of his generation. Sidibé is renowned for his black and white photographs that joyfully document Mali’s ebullient youth culture, which emerged following the post-colonial era of the 1960s and ‘70s. It was a time of great transformation, and Sidibé played an important role. Through the medium of photography he not only recorded––he aided and abetted a cultural and social revolution.

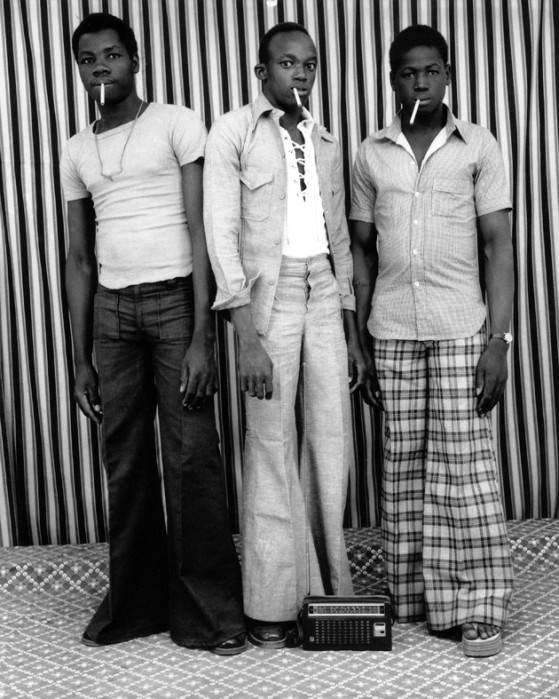

Untitled, circa 1970.

Malick Sidibé was born in Soloba, a rural village where, from the age of five, he herded family goats. In an interview in The Guardian, he recalls that his mother decorated huts in the village with simple designs of lines and circles––perhaps that was the genesis of his early interest in art. At the of age ten, he was the first child chosen to attend the white school. He excelled in drawing skills and took pride in his ability to imitate nature. His abilities were quickly recognized and he was rewarded with art books, one of them about the artist Delacroix. He also excelled in high school, and then was selected to further his art and design education in Bamako, at the École des Artisans Soudanais, where he graduated from in 1955.

In 1956 the French expatriate photographer, Gérard Guillat-Guignard hired him initially to decorate his studio and later to man the cash register, deliver photos, handle cash and sell equipment. Guillat-Guignard did not teach Sidibé how to take photographs. Sidibé knew that he wanted to be a photographer and he already had a developed knowledge of light and shadow from his years of drawing and painting. He also carefully observed Guillat-Guignard. “I was used to working with pictures. I found that the camera was a lot faster than a paintbrush. So I threw myself into photography and that’s how I became a photographer,”

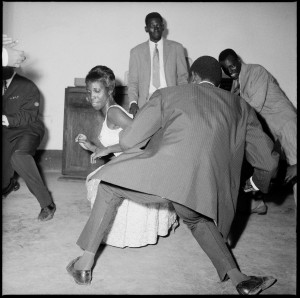

Untitled, circa 1960’s.

After a year, Sibidé bought himself a cheap Kodak Brownie with a flash. While Guillat-Guignard photographed dignitaries and colonial events, Sidibé shot weddings and other events in his own community. Soon he was in demand, invited to document dances and social clubs that were beginning to happen in Bamako. “You are called. You are recommended in advance, so you go to someone’s wedding, someone’s christening… We were recommended, and I was lucky enough at that time to be the intellectual young photographer with a small camera who could move around.”

Untitled, circa 1960’s.

Sidibé was sociable by nature and attuned to the aspirations of the Bamakois youth. He followed them but was also a co-conspirator as they performed for his camera. When rock and roll music and the youth quake culture that swept England and the U.S.A. arrived with a rebellious rumble in Mali in the late 1950’s, Sidibé proclaimed that music was the real revolution. The youth of Bamako immediately embraced the musical revolution as their own. They were enamored with the Rolling Stones, Aretha Franklin, The Beatles, Jimi Hendrix and James Brown, but also the twist and the bugaloo. The young Bamakois were fantastically stylish and used their finery of bell-bottoms and paisley to assert their modernity.

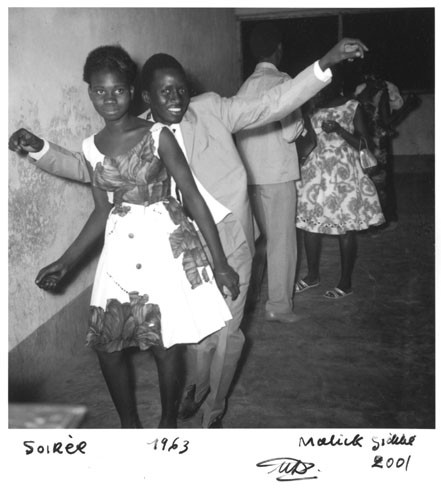

The new music broke down social restrictions between the sexes. Sidibé said, “Music liberated African youth from the taboo of being with a woman. They were able to get close to each other, which is why I was always invited to these parties. I had to go in order to record these moments, when a young man could dance with a young woman close up. We were not used to it.”

Untitled, circa 1960’s.

Sidibé’s images taken at the clubs are wonderfully composed, capturing the action of the dancers as motion and energy in space. In these photographs, freedom and joy are palpable and music is made visible.

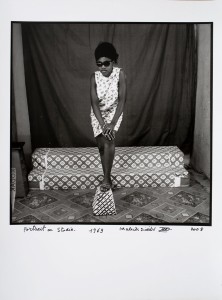

In 1958 he opened Studio Malick in Bamako. “It was like a place of make-believe… People would pretend to be riding motorbikes, racing against each other… As a rule, when I was working in the studio, I did a lot of the positioning. I didn’t want my subjects to look like mummies. I would give them positions that brought something alive in them.”

Dancer le Twist, 1965.

Bamako already had an established and important photographer, the great Seydou Keita who had opened his studio in 1948. His elegant, carefully composed portraiture reveals an intimate connection to his clients and contain a dignified formality. Carefully staged, with subjects often posed in front of beautifully patterned fabrics, Keita worked with a large format camera. His studio photos render in detail, jewels, clothing and props to portray an elevated social status.

Sidibé and Seydou rarely saw each other, although Seydou did bring his camera to Sidibé’s studio for repair. Though from different generations, they did have some common approaches to their work. They both provided a range of props and clothing to help their clientele express their aspirations, and both of them directed client poses to achieve optimal results. Both men were masters in working with light. Each of them produced massive amounts of negatives and was meticulous in maintaining their archives. Both were unknown in the West until the early 1990’s, after which both achieved international acclaim and fame.

Soirée, 1963.

Sidibé’s young clients rejected Kieta’s formal studio approach as too conservative for their generational revolution. They needed a new photography for their new visions. “When you look at my photos, you are seeing a photo that seems to move before your eyes. Those are the sort of poses I gave them. Not poses that were inert or lifeless. No. People who have life need to be positioned that way.”

Manthia Diawara, the noted scholar and filmmaker was a teenager in Bamako during the 1960’s and a part of the youth movement. In his essay ‘The Sixties in Bamako: Malick Sidibé and James Brown’, he wrote “To say that Bamako’s youth is on the same page as the youth in London and Paris in the 1960s and 1970s is also to acknowledge Malick Sidibé’s role in shaping and expanding that culture… To the youth in Bamako, Malick Sidibé was the James Brown of photography: the godfather whose clichés described the total energy of the time.”

Fan de James Brown, 1964.

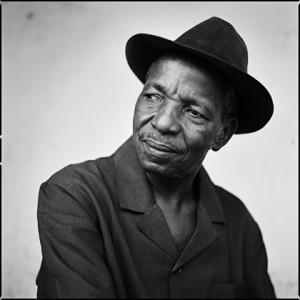

Malick Sidibé was part of the fabric of his community. His clients were his community and he captured them with their yearnings and dreams. In all their hipness and beauty, they are full of life. His portraits challenge pervasive stereotypes of the primitive other, living unhappy lives in poverty-ridden misery.

Sidibé is complicit in their performances; the images are created in collaboration with his community. He directs them; posing them and providing the props that they need to perform and assert their identities in the mirror of his images. Their wish is to be modern; they identify as free people, and have hope for lives unhampered by colonialism or the nation state. They reach for more. Sidibé’s images support the aspirations they strive to attain. They dream of liberation and freedom. Sidibé’s photographs prove that the dream can be real. His images intimately connect the viewer to the dreams of the people of Bamako.

Portrait au Studio, 1969.

In the late 1900’s after Sidibé had become famous and European and American collectors flocked to his studio, clamoring for his work, Sidibé began to sell his vast archives of negatives. He even gave many away. One can only imagine what treasures the world has lost. Sidibé’s generous and joyful spirit may be what made him such an effective conduit for Bamako’s youth cultural revolution.

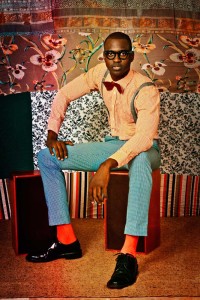

Omar Victor Diop, Thierno, 2012, courtesy Magnin-A.

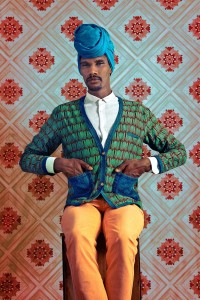

Omar Victor Diop, Joël, 2011, courtesy Magnin-A.

Malick Sidibé’s photographs have inspired and influenced many artists, including Omar Victor Diop, an important young artist from Dakar, Senegal. His photography includes staged portraiture and self-portraitures and fashion. In his studio portrait series entitled ‘The Studio of Vanities’, Diop has photographed artists from his creative circle of friends in Dakar. These portraits, like those of Sidibé’s, were created in collaboration with the people of Diop’s own community. They mirror what’s happening in his modern generation.

Earlier this year in Paris, Diop showed his portraits with those of Sidibé’s. Diop remarked in ID Magazine, “It’s like showing with Cartier-Bresson or Avedon. He’s had a tremendous influence on photographers of my generation––not only African.”

Inna Modja, Tombouctou.

Another notable artist Sidibé influenced is the Bamakois singer and songwriter Inna Modja, who is a protégé of Salif Kieta, known as the “golden voice of Mali”. She bravely asserts her right to be an overt change agent. An advocate for anti-violence and women’s rights, she sings out against female genital mutilation. She calls for freedom at a time when that is an exceedingly dangerous thing to do.

In her music video, ‘Tombouctou’, Modja stakes her claim as an heir to Bamako’s cultural capital and Sidibé’s legacy, choosing to film her powerful, anti-violence, anti-war woman empowerment protest song in his studio. She pays tribute to him with layered visual imagery, framing and performance gestures that reference the Sidibé aesthetic.

Janet Jackson, Go till it’s gone, 1997.

Sidibé’s influence has impacted every aspect of the fashion world including textiles, clothing designers, stylists, and magazines, from layout to photography. In addition, his work is frequently referenced in popular culture. Janet Jackson won a Grammy Award in 1997 for her ‘Got Till its Gone’ music video, a Sidibéan visual inspiration.

Malick Sidibé leaves an indelible imprint on contemporary photography. His iconic work counters persistent stereotypes and racist representations of Africa and Africans. Beyond capturing the ultra stylish hipness of his post-colonial cohorts, Sidibé joyfully affirms the lives, identities and aspirations of a generation reaching for freedom and asserting their modernity into the world. Beyond that, his photographic images have become part of a visual lexicon that resonates and extends to communities worldwide. Because of his transformative mirror gaze, Malick Sidibe’s photographs will continue to be catalysts for joy, hope, strength– reminders of what real freedom can be – reminders that a new generation can create a joyful freedom revolution. That is a legacy the world can use for generations to come.

Unless noted otherwise the original source for all Malick Sidibé quotations used in this essay are taken from a translated transcription from a video interview recorded in Rouen, 2008 and produced by Jerome Sother for www.gwinzegal.com. The full interview in English appears in Lens Culture: www.lensculture.com/articles/malick-sidibe-interview-with-malick-sidibe