(…) from the overwhelming restrictions in Tehran to the growing freedom of artistic expression in Kenya, Bolouri has found a small platform in Nairobi, where she can express the senselessness of certain norms that persist in society. Subtly expressing the thoughts that many of us think but don’t dare voice, this bold, observant artist doesn’t care if she has to dance alone.

Zihan Kassam on the work of Maral Bolouri.

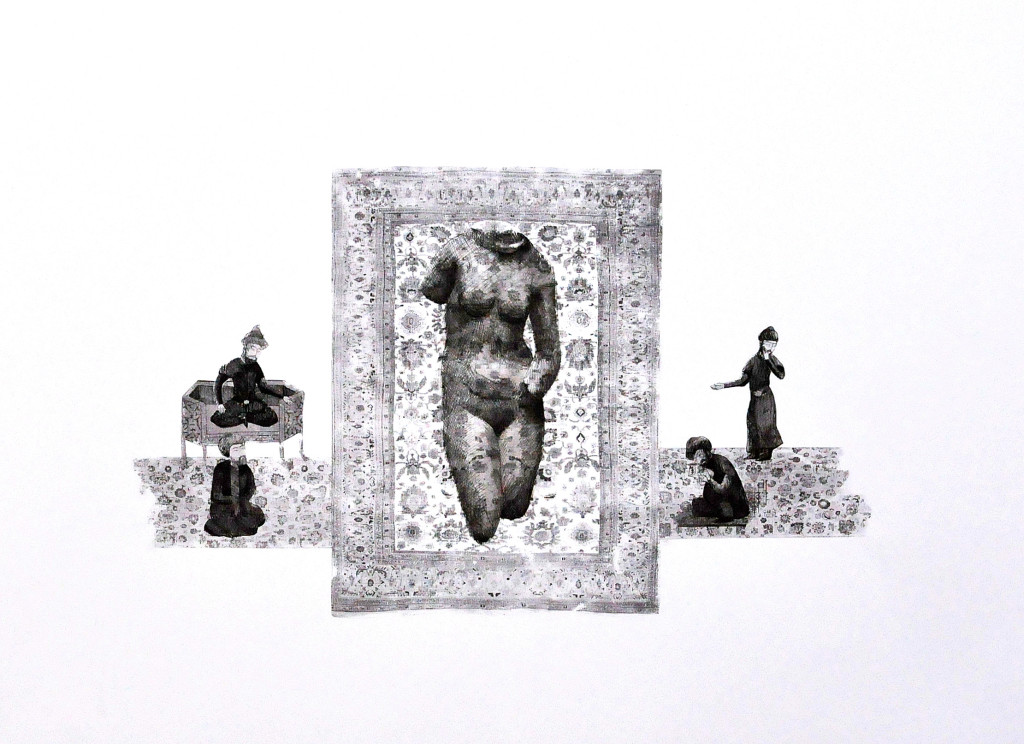

The Holy Women, 2015.

RESERVED FOR THE BRAVE

MARAL BOLOURI

The world is a carnival and we are all in fancy dress. We talk a good game. Parading our vacuous thoughts with acumen, we can have extensive conversations about nothing. In a world where wisdom has surrendered to trivia, it is increasingly difficult to meet people who are modest, unassuming; those who don’t waste words.

But once in a blue moon, in rooms full of hot air, you find someone who engages you in meaningful discourse. These are the people who don’t care as much about how successful they appear as they do about engaging in issues that make life for more tolerable for everyone. In a world where nothing feels sacred anymore, these are the individuals who have made the difficult decision to engage in issues that are not easy to handle.

In her discourse and all through her artwork, Maral Bolouri is a bona-fide minimalist, a refreshing, careful, introspective creature who will win you over with just a few choice statements and image placements.

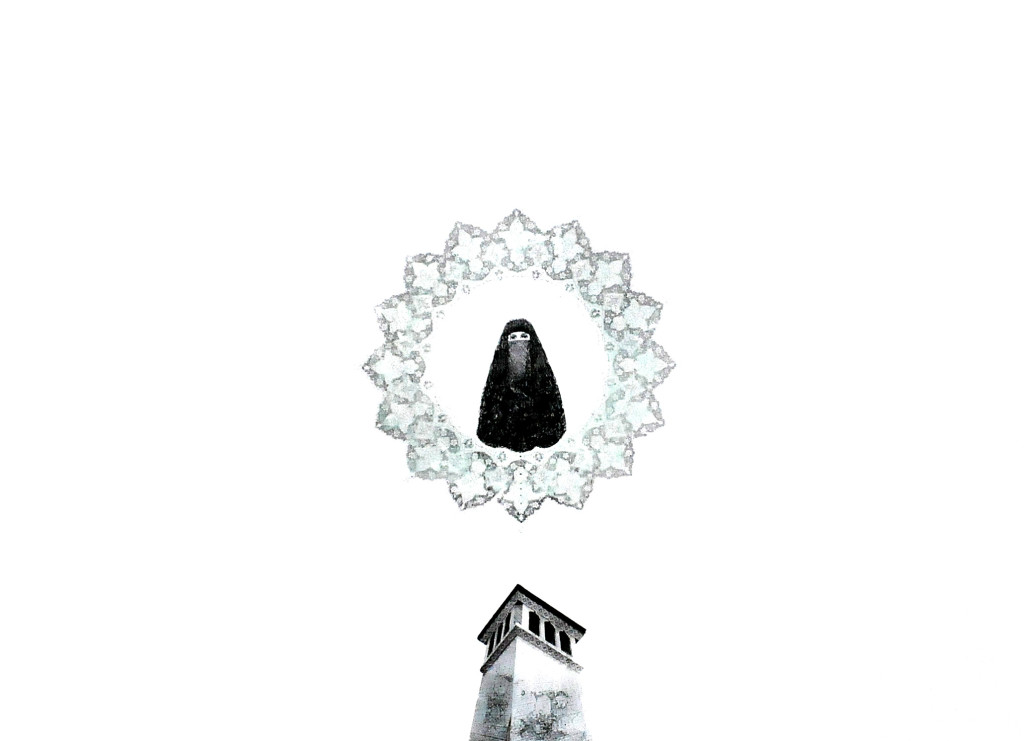

Untitled, photocopy transfer and-pen on paper, 2015.

From the word for ‘fate’ in Farsi, Bolouri brought us Sarnevesht, her solo exhibition at Kuona Trust Arts Centre in Nairobi last month. The exhibition was curated by Danda Jaroljmek from Circle, the Kenyan art agency making waves on the East African scene. Earlier this year, Bolouri’s artwork was featured at Concerning the Internal, the group exhibition that marked the launch of Circle Art Gallery in April 2015. Since moving to Kenya in December 2012, Bolouri has exhibited in several exhibitions including the Barclays L’atelier Competition, Finalists Exhibition at The National Museum of Kenya in April 2015. Inspired by her past, by history, and by current affairs in Kenya, she delves into provocative subject matter. Taking risks with her message, it is an occupation reserved strictly for the brave.

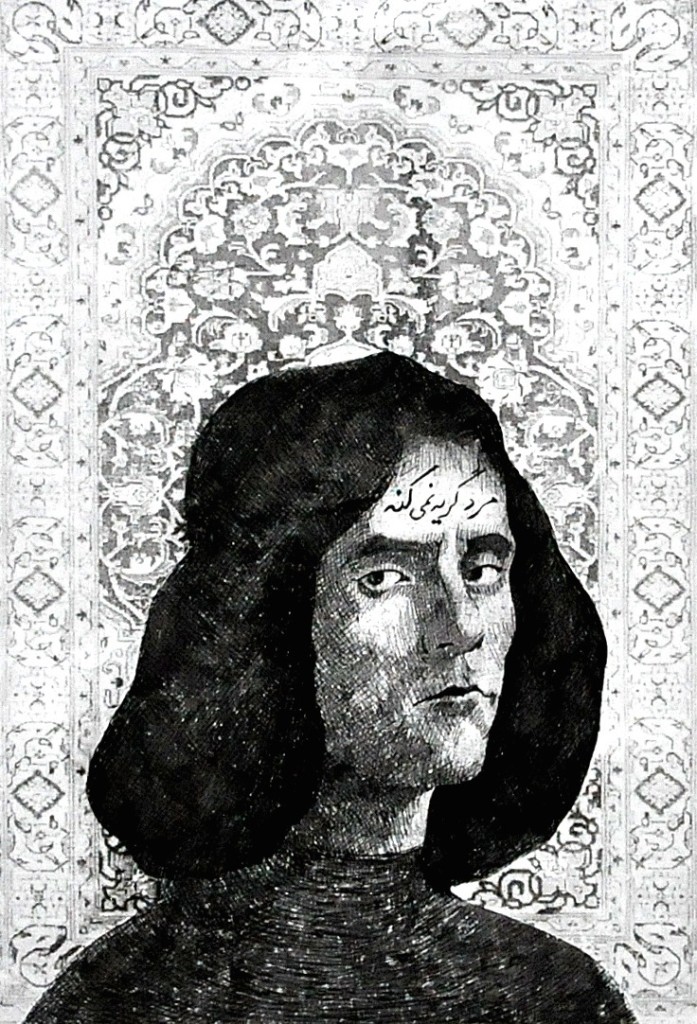

Untitled, photocopy transfer and-pen on paper, 2015.

Featuring elements of Persian miniature painting including Persian motifs, Persian architecture and illustrations set within rectangular booths, the twenty-two images at Sarnevehst were well-groomed black and whites with a heavy reliance on negative space. All of them photocopy transfers with ink-work and drawing, Bolouri worked on a series that explored culture-based gender discrimination. She concentrated on the effects that religious texts have on the roles and treatment of women. Looking at the effects of tradition and law in different societies, the artwork explored the unreasonable demands made of women, the inequality in freedom between the sexes and the details of our irrational gender socialisation process. It raised questions about the collective constructs we blindly accept and sustain.

The six portraits at Sarnevehst each had a different Persian carpet motif as background. With their sombre stares, each countenance was desperate. In ‘Farsi’, Bolouri penned a gender stereotype across their foreheads, a decree that limits their freedoms and constrains their behaviour. A woman should be decent, A woman should be compliant, A woman should be a housekeeper, A man doesn’t cry: every tenet, as prescribed by customary laws, confined the men and women to a solemn reality, one of limited prospects. Each character appeared frozen in time, inert, eternally shackled by these dire expectations. The most potent title read: A man should have Ghirat: a man is allowed to act in a jealous or possessive manner.

Untitled, photocopy transfer and pen on paper, 2015.

The woman in a black hijab, referred to as the “holy” or “respectful woman” in Bolouri’s titles, is a motif that runs throughout Sarnevehst. Other Sarnevehst insignia include nude statues akin to first century Roman sculpture, like the famous torsos of Aphrodite or Apollo. These photocopy transfers were placed at the centre of several of Bolouri’s compositions, where their state of undress was contemplated by men and women from an indistinct religious sect. With a quasi-temple icon somewhere in the image, the message is that the convictions of certain religions have led their believers to be offended by the human body – the very body they believe was created by a higher power.

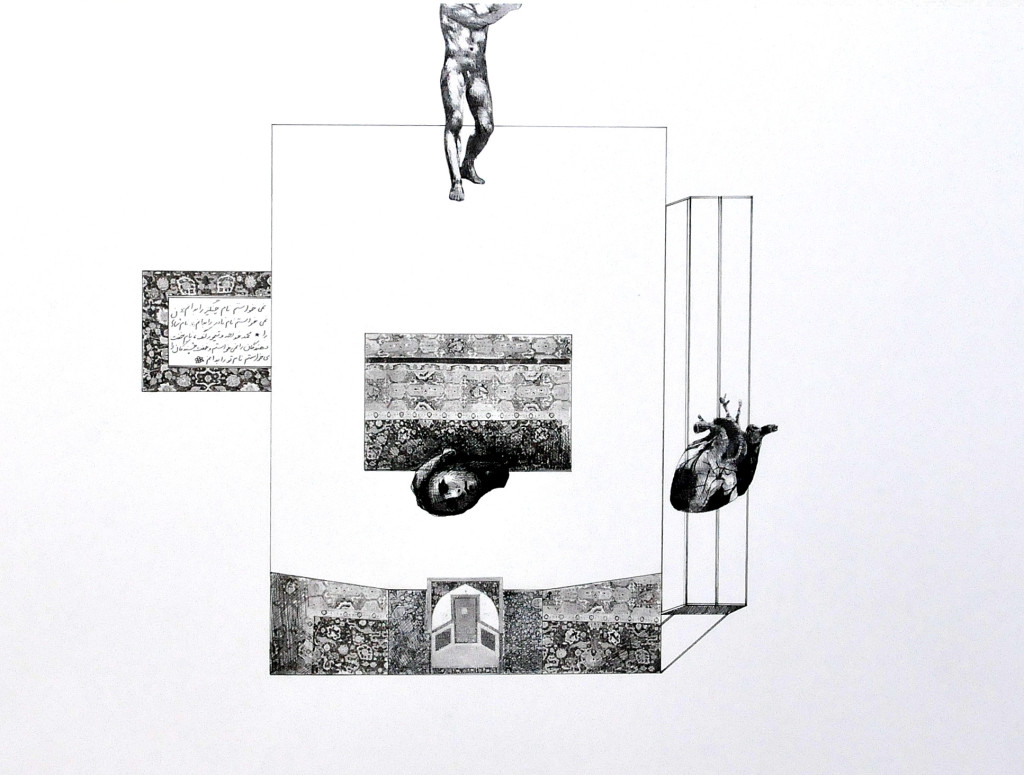

Untitled, photocopy transfer and pen on paper,2015.

The satire in Bolouri’s work is readily perceived by those who have ventured out of the realm of blind faith. Delicately contrasting eastern and western values, her ingenious pictures play tricks on us, triggering questions about our belief systems. The Venus, for example, Roman goddess of love, beauty, sex, fertility and prosperity, adored by most of Europe, is offensive, even blasphemous to people of certain religious denominations. Bolouri incorporates pseudo-religious iconography, and for the intuitive folk, some subtle phallic symbolism. Using provocative titles like ‘Shut up and keep your hajab’ and ‘This is what happens when you don’t listen’, she alludes to the adverse repercussions of certain doctrinal teachings.

In her Sarnevehst video, volunteers from different cultural backgrounds were asked to come up with a gender stereotype that they have been pegged with. In the first half of the clip, each participant has one of these stereotypes, not necessarily the one associated with them, scribed on their forehead. In the second segment, each person ties a bandana with the same label on to his or her own forehead. The performance is an abstract oeuvre, hinting at the human tendency to assimilate the labels that others brand us with. A self-fulfilling prophecy, people seem to mould themselves to fit the roles that our culture and larger society expect of us. This is driven by a need to be accepted, to feel a part of something but also the fear of rejection and fear of the law.

Bolouri tells us about the objects in the glass cabinet at the Sarnevehst exhibition at Kuona trust, which included an ornate pen-case, a pill-box and a fancy book of poems. “I wanted the viewer to interact with something other than the photocopy transfers. Danda Jaroljmek came up with the idea to exhibit some items from Iran, because the Kenyan viewer might not be familiar with Iranian culture and history. We included a selection of ancient and contemporary Iranian poetry, mostly about love and humanity.”

Untitled, photocopy transfer and pen on paper, 2015.

Born in Teheran in 1982, Maral Bolouri grew up with a collection of art books at home. “With limited access to television, I would flip through the images in books but I couldn’t understand the English. In school things were very strict then,” she says, “Post-war Tehran didn’t have many activities for kids and you couldn’t really be a kid. People treated you like a grown up all the time. But at home, my brother and I had access to crayons, watercolours and art pads and we were encouraged to experiment with drawing and painting. That is how it all started.” Bolouri’s father, a civil engineer, and mother, an interior architect, were both interested in art and music. Their home in Tehran was filled with paintings, photographs, and a large vinyl collection. Bolouri enjoyed drawing more than painting, “from the start.”

Untitled, photocopy transfer and pen on paper, 2015.

Maral Bolouri met her grandfather, a political refugee, when he was pardoned after the war and returned to Iran from Greece. “He would spend his time reading and drawing. He was an amateur artist and I would always admire his artwork. He was a great inspiration to me.” She came from close-knit family and she tells us that when she lost her grandfather, her grandmother and aunt suddenly, all within a short span of time, her grief ran deep. And like many artists out there, without the words to communicate her pain, she learned to express herself through drawing. Carrying her sorrow and also, the distress from the tensions in Iran, Bolouri had witnessed the injustices of the world and was sharing them using her artwork.

In her last year of high school, Bolouri attended private art classes under the mentorship of award-winning Iranian graphic designer and illustrator Hafez Miraftabi whom she says, “opened her eyes to a world of drawing, poetry, art history and drama.” In 2001, she enrolled at the Soureh University of Fine Art followed by a BA at the Art University of Tehran.

She graduated in 2008 and later pursued a Master’s program in Malaysia at the Limkokwing University of Creative Technology, where she completed a research-based course in International Contemporary Art and Design Practice. Bolouri met Andrew Mwini at Limkokwing, an artist studying Graphic Design. The two fell in love and Bolouri moved to Kenya, where they currently share a studio at Kuona Trust Arts Centre in Nairobi.

Photo: Anthony Wachira

And so, from the overwhelming restrictions in Tehran to the growing freedom of artistic expression in Kenya, Bolouri has found a small platform in Nairobi, where she can express the senselessness of certain norms that persist in society. Subtly expressing the thoughts that many of us think but don’t dare voice, this bold, observant artist doesn’t care if she has to dance alone. In the deafening spaces, where the rampant chatter hurts your sensibilities, Bolouri remains cool, consistent and down to earth. Never afraid to hit you with a reality-check, to speak about the callousness that permeates our world, or to expose the hypocrisy in society through her artwork, she rarely loses her perspective or her voice.