During the last few years discussions have been going on in The Netherlands, addressing colonialism and its complex influence in the present. This discussion is most present in the field of arts, where exhibitions show artists who counter eurocentrism while reflecting upon their own identities, upon humanity and inhumanity. Pinas’ art works resonate with this discussion, as he is already rather entangled in the fabric of the art world, in Surinam as well as in The Netherlands.

Machtel Leij on the recent exhibition Tembe Afaka of the Surinamese artist Marcel Pinas.

Marcel Pinas: Tembe Afaka

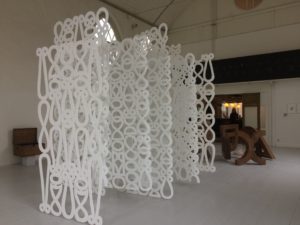

All color seems to have drained from Marcel Pinas’ art works. Black and white shapes stand out in the exhibition ‘Tembe Afaka’, at the Hotel Mariakapel, Hoorn, The Netherlands. From the ceiling, in the middle of the former chapel, hang layers of white, wooden boards. In this installation, the color white acts as a counterbalance to the crayon lines that fly from the floor to the walls, on huge sheets of paper. This work looks as if the artist maniacally drew his lines and shapes, turning parts of the white of the paper into a deep black. A stub of crayon is left behind as definitive proof of the actions that have taken place.

When encountering Pinas’ installations, it is as if one enters a three-dimensional world that essentially started out as two-dimensional, as the basis are written and drawn lines. All shapes spring from Afaka: a syllabic writing dating from the beginning of the twentieth century, expressing the N’dyuka language. This creole language was spoken by Maroons in parts of Surinam, once a Dutch colony that became independent in 1975. Pinas was born in 1971, in Marrowijne, Suriname, near the town of Moengo where he still lives. The N’dyuka language, on the verge of disappearing, comes to life in the hands of Pinas’ tumbling and swirling line drawings and shapes, which, not incidentally, are based in the wood craft tradition of the N’dyuke, called Tembe.

Inherent playfulness is countered by the weight and the shape of huge metal symbols that cluster together near the entrance in Hotel Mariakapel. Shapes out of the Afaka alphabet are translated into sturdy and rusty metal. Scattered over their surfaces are scarce markings, scratches and fingerprints, left behind by the hands that handled the objects. These fingerprints aren’t those of the artist per se, as the iron objects are produced by a company. But these signs of human activity fit this exhibition. By leaving his crayon mid-action on the paper he drew on, Pinas shows how his work came into being, wanting to make clear how this art work is produced by his own hands.

The result of his actions is a quiet and stylistic exhibition. High up the wall, glass signs form a sentence in N’dyuka, written in Afaka. It is, he explains to me on the phone, a sentence that stresses the importance of being attentive to how we deal with the natural resources of the earth, taking future generations into consideration. ‘The Maroons live in the jungle. They only take what they need and nothing more. There is a lesson to be learned from this, especially for Europeans who looked down upon Maroons, questioning their intelligence, in part because of how they lived. However, a people that has developed its own language and writing is unmistakably intelligent’, Pinas stresses. At the same time Pinas wants to create something new, adding to the language that is on the verge of extinction, thus reviving it. During a residency in Jamaica in the nineties, he decided to draw inspiration from his own back ground and culture.(1)

Pinas: ‘I react to the exhibition space itself, while working at the spot.’ In Hotel Mariakapel Hoorn, it evokes an introspective feel, especially in comparison to his previous installations, that ooze life and color. He paints, sometimes adding the characteristic cloth with geometrical patterns produced and worn by Maroons on his canvasses and in his installations that he forms out of materials that outline the modern life of Maroon people: bags, shoes, bottles wrapped in Maroon fabric. The dancing linear shapes of Tembe and Afaka symbols appear in color, painted onto canvas, and onto objects connected to the everyday life and history of N’dyuka.

*

Pinas began the Kibii Foundation in 2009 that organises art manifestations as well as the Moengo Triennial. This recurrent exhibition is meant to invigorate cultural and social life in Moengo and surroundings. (2) There he founded in 2010 Tembe Art Studio, an artist-in-residency. Local artists and artists from abroad meet there and influence one another; also the youth of Moengo takes part in workshops. Every participating artist is asked to contribute a work of art to the ever growing Marrowijne Art Park that was founded, near Moengo, also by Pinas. The artist has extended the sphere of influence of his art to the realm of the social. All Pinas does, he does under the motto Kibri a Kulturu, protect the future as he calls it. (3)

Hotel Maria Kapel, Hoorn

During the last few years discussions have been going on in The Netherlands, addressing colonialism and its complex influence in the present. This discussion is most present in the field of arts, where exhibitions show artists who counter eurocentrism while reflecting upon their own identities, upon humanity and inhumanity. Pinas’ art works resonate with this discussion, as he is already rather entangled in the fabric of the art world, in Surinam as well as in The Netherlands (he attended the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam and is shown regularly in Dutch art institutions). (4) Pinas guides his public via the present to a possible future, fiercely underlining the importance of embracing cultural heritance.