Being able to express oneself without words is a powerful tool in making wellbeing accessible for those without the confidence to voice how they feel. Experiencing emotions vicariously through other’s work, whether they are your own emotions reflected or new ways to empathise with others, is a priceless gift. And in the economics of health, art is a valuable currency which has an international value.

Christabel Johanson on Mental Health in Black Art

Tsoku Maela, redifining mental illness

Mental Health in Black Art

During these uncertain times it is easy to feel the stress of the world mount up. 2020 has been a particularly charged year with the COVID-19 scare, protests and tumultuous weather. Lockdowns have forced the world to stay indoors and as such rates of depression, anxiety and suicides have increased.

When our worlds get that bit smaller, we are sometimes confronted with the demons of mental health. If this is something forced upon us rather than by choice, it is easy to fall into unhelpful thought patterns or worse. For certain cultures in the BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) communities mental health is still a taboo topic. Individuals do not feel able to share their issues or even acknowledge its existence.

This is why it is so important for society to explore these topics, not only intellectually but also through the arts. For artists, their work becomes a platform of expression for themselves and others seeking refuge and healing.

Art for wellbeing is more than just a fad. According to the Mental Health Foundation, ill mental health accounts for more than 20% of the public health challenges in the UK. Imagine this across the world. Not only is making art a therapeutic process for the artist, but viewing it is just as beneficial for the audience. Gathering together – whether physically or virtually – also creates a space for social interaction, discussions and builds a community of support. During lockdown many people turned to a creative outlet to vent their fears and frustrations. Colour therapy, mindfulness plus the joy of having an instant piece of art in your living room promotes the healing power of creativity.

For those in BAME communities the awareness and visibility becomes even more important. Below are three artists from these backgrounds who tackle mental health themes within their body of work.

Heather Agyepong

Agyepong uses powerful imagery to document mental health concerns as a black woman. “My art practice is concerned with mental health and wellbeing, invisibility, the diaspora and the archive”. By using herself as the central subject she reconstructs imagery for the audience to engage, work through and experience their catharsis.

As wellbeing is at the heart of her art, as a black performer Agyepong is aware of the setbacks and obstructions within the community in embracing a different perspective on mental health issues. “I think mental health is particularly relevant for the black community because in the UK we are more likely to suffer from a serious mental health condition than our white counterparts. A lot of us have a distrust of the health care system from past failings and there is a general taboo around the subject. I wanted to contribute to the conversation as I don’t want the future generation having any blocks to these conversations and seeking help”.

Le Cake-Walk: The Body Remembers (#4), 2020, (Commissioned by The Hyman Collection)

The work focuses on her own imagery through self-portraits, for Agyepong her culture and race are inseparable components from her art. “It feels like anything a black woman does is political and I’m interested in taking back the gaze and curating my own story, my own narrative, and my own power. What can I say with my body that can empower myself and others? Maybe I’m a romantic but I truly believe art can affect change so I try to make my personal experiences and give them a voice/a frame to speak truth to my experience be it as a woman, a black person, a young adult or whatever other lens people wish to see me through”.

Untitled, From “Too Many Blackamoors”, 2015

Her Too Many Blackamoors series features her exploring the narratives of the19th century as the central subject. This time travelling perhaps offers a comparison on how antiquated contemporary society’s attitudes and offerings are towards the Other, including Other mental states. After experiencing her own challenges from her mid-teens to early twenties, Agyepong connected with photography as a means of capturing emotions – even the uncertain feelings.

Uncertainty is something which characterises 2020. With so much left to be seen, plus the long stretch of lockdowns, mental health issues are at the forefront of our collective consciousness. For Agyepong and others in the black community George Floyd’s death, which happened during that period, was a huge catalyst. “It felt like an earthquake had happened worldwide and for black people we were in the aftershock for weeks (still are). A lot of us were collectively disorientated, disordered, things rose to the surface”.

“For me there was a lot of anger, shame, frustration but a beautiful sense of entitlement. Although we mourned for this man we didn’t know we also mourned for times we never spoke up, or allowed institutions/friends to be vague or perform ‘wokeness’. So much self-reflection and a deep longing to gather. We really need more spaces to gather, to be held, to cry, to be real. Vulnerability is a devastatingly powerful thing that doesn’t always need to be on display for others”.

Kirsty Latoya

Latoya is known by her handle “KirzArt” and specialises in digital realism. Her modern style (created on an iPad) focuses on different emotions. She is passionate about “translating modern issues” about mental health into meaningful illustrations.

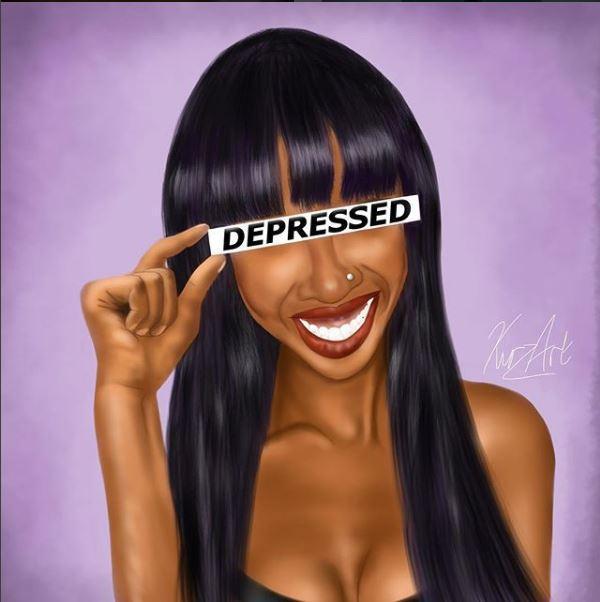

For her Emotions series (2016-2019) Latoya captures situations that are relatable to contemporary black youth. For example The Face Behind Depression shows a young woman (perhaps a selfie of Latoya) seemingly happy with a big smile. Yet her eyes are obscured with the caption “Depressed”. One reading is that whilst many seem happy, their true feelings are different. This piece makes depression particularly relevant for young people who have to create the perfect imagery for social media.

The Face Behind Depression

Black men are also a demographic who have been difficult to engage when opening up about mental health problems. The piece below portrays the patriarchal reaction towards depression; the idea that one needs to “man up” and overcome a space which is notoriously disempowering. Perhaps by highlighting the lack of empathy or support between the men of the picture, Latoya asks her audience what they could do different if they were in that situation.

The artist herself had dealt with depression in her early teens due to a genetic condition that had a deep impact on her youth. It was also the same genetic condition that cost her mother’s life. After overcoming these tragic setbacks early in life Latoya found a purpose for her art.

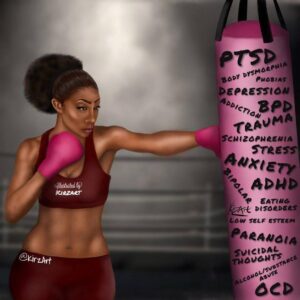

Echoes of this spirit can be found in Fighter below. We see a woman punching a boxing bag with mental health conditions and disorders scrawled on such as “PTSD”, “Bipolar”, and “Anxiety”. Behind the strong physique of the figure lies our own vulnerabilities but also the ability to resist and fight back.

Fighter

Latoya has gained the attention of the BBC and other media outlets for her mental health work which all help to raise awareness for the cause. She published her book Reflections of Me in 2018 which further explores mental health and identity through her visual work and poetry.

Tsoku Maela

Through his photography, this Cape Town native brings another approach towards documenting mental health challenges. Abstract Pieces is Maela’s series of pictures forming a visual diary of someone at different stages of depression and anxiety. “Mental illness in black communities is often misunderstood, misdiagnosed or completely ignored. Depression isn’t all doom and gloom, it’s an opportunity to face oneself and this is a result of going to places you hate the most about yourself and finding beauty”.

A brief reminder of solitude

South Africa’s history of racial polarisation has seen mental health issues as a “white problem”, which has spread a lot of misunderstanding and fear around those issues. Destigamatisation is often achieved through exposure and education. Maela’s work is still settling into South Africa. It is mostly Europeans who appreciate the conceptual nature of the photographs more than the African community. However as with most things, time will tell.

Social commentators are quick to point at poverty, racism, marginalisation and other social problems as major contributors towards the mental health of black communities. Yet understanding this does little to offer a solution for the struggles of Afro-Caribbeans.

Here is where art steps in. Being able to express oneself without words is a powerful tool in making wellbeing accessible for those without the confidence to voice how they feel. Experiencing emotions vicariously through other’s work, whether they are your own emotions reflected or new ways to empathise with others, is a priceless gift. And in the economics of health, art is a valuable currency which has an international value.