Mncedi Madolo’s work has so much room for growth and so much incredible potential to explore the mediums, subject matters, and materials in ways that will truly enrich his work. If one has time, please do visit his studio at Ellis House Art Building or search for his work online to make your own judgment.

Athi Mongezeleli Joja on the South African artist Mncedi Madolo

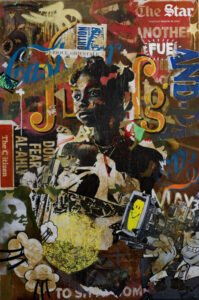

Jungle IIV

Mncedi Madolo

It’s a Sunday afternoon in Johannesburg. The wintry chills have many walking like they holding babies whilst tiptoeing through a landmine. Shuffling crowds come in and out of the entrance of Ellis House Art Building, exchanging mumbles behind their masks. I cut through the restless crowds like a hot knife, with the eagerness of avoiding the typical exhibition small talk. Because the Covid-19 pandemic has normalised itself through time and space, I cannot really recall when last I visited Ellis House open studios. The justifiable paranoia that treats human interaction as if it were itself the virus, has been the more than perfect excuse to stay far from certain people. “A very cold and distant nod would suffice for this one” I tell myself. After all, it is cold.

From around the corner, the pleasant sound of legendary double bassist Herbie Tsoaeli’s 2012 album, African Time, permeates the industrial passageways through the miasma of masked talk, small talk, drunk talk, foot steps, and other sounds crisply circulating about. I finally arrive at Mncedi Madolo’s studio. The first encounter is neither the art nor the crowds dizzied by Madolo’s artistry, but a young black couple with a toddler waltzing to Tsoaeli’s Afrika Entsha (new Africa). The co-presence of multiple eras (embodied by the dancing family) is precisely what Tsoaeli’s song attempts to capture by imagining the possibilities of a “new Africa,” as it were, as opposed to the cynicism that sought to confine it to an atemporal zone of unflinching stillness. Here, Tsoaeli demonstrates an optimistic, if not celebratory, comportment of African temporality instead of complying with the schedule of the world. A befitting welcome!

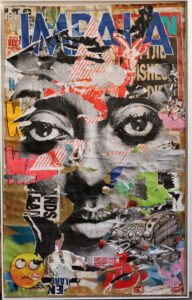

Impala

Ellis House Art Building is amongst the prestigious and spacious studio spaces in Johannesburg, that has primarily housed a considerable number of notable figures in our local art scene. Mncedi Madolo finds himself in this maze of recent history, creative buzz, and he too is eager to make the opportunity count. The studio is significantly large in size, and the artist has subdivided it into working and living areas. As already mentioned, the studio was slightly congested, with a considerable number of people absorbed and fascinated by the presentation. Madolo reconstructs popular motifs and imagery to not necessarily, as it was initially intended with collage work, to temper with our sense of seeing but rather to project to us how our worlds constantly make and remake themselves. I will explain this just now. The notion of the open studio which has been popularised in recent years, is meant to expose all kinds of publics to the catalogues of works artists do, be it finished, unfinished, or even at preparatory stage. Indeed, from finished oil paintings (portraits, groups and landscapes) to his noticeably familiar selection of his collage works (finished and still in preparation stage). The audience not only gets to see the vast array of skill and range of the artist, but also bear witness to the space where all “the magic” happens.

Contemporary studios have taken advantage of a rather old practice of studio visits whereby hybrid contexts are constructed such that artists don’t only demonstrate their skills in real time or collaborate with an interested public in a kind of workshop context as was the case of open studios before. In other words, current open studios platforms apply the technology of display typical to galleries and museum spaces as well as expose the audience to the behind-the-scenes i.e. to the artist’s entire range and the mediums they use. What is left for the artist to do is mingle with their public on a one-on-one basis.

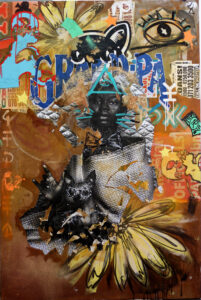

Grand-Pa III

This, of course, is how Madolo engaged his visitors, who ranged from potential buyers, art enthusiasts, other artists, journalists, ordinary folk and so on. He’d shuffle from one corner to another, attending to a curious visitor’s inquiry about anything related to his work, be it his large collage images lined up along the main wall with their assortment of collage cut-outs laying on the floor or his makeshift photographic area, complete with all the photographic props (backdrop, umbrellas, lights, tripods). A couple of books and articles also lay strewn around the studio table, and I notice in particular, two texts linked to the Black radical tradition, namely Zoe Whitley and Mark Godfrey’s Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963–1983 and a seminal article by Julian Mayfield, If you Touch my Black Aesthetic and I’ll Touch Yours. Alongside it also lay a couple sketches and drawings, and I recall being particularly drawn to Madolo’s cartoon imagery. It appears, the artist dabbles on occasion, in the comic arts and has enjoyed a feature or two in a couple of local newspapers.

My attempt here is not to write an expose on Madolo’s art but rather to offer an introduction to the work through a series of general descriptions. I am, however, uncertain that such an approach will pass muster in the field of art writing. If anything, it might even come across as presumptuous. To appease the sensitive, let me briefly state why this is crucial for me. In a context where representation, institutional representation in particular, is the means by which knowability and justice is achieved, we cannot easily assume that people who are not represented can be guaranteed an equal experience to those who are. Consider how, for example, in our criminal legal systems, an alleged felon without legal representation runs the risk of spending an incredible amount of time in remand detention, waiting for their day in court. Basically, the primacy awarded representation or the represented in the democratic paradigm crowds out the self-represented and unrepresented into the margins.

The same could be said about how we come to know and interact with our visual artists, particularly black artists, who are not on the catalogue of cultural institutions. Representation is often what determines one’s fate; whether one achieves obscurity or celebrity. Many artists like Mncedi Madolo find themselves having to navigate the concrete jungle of the art world without representation. By this, I don’t necessarily place institutional representation above self-representation and independence, but what I want to underscore is the normalised monopolisation of administrative capacities by institutions. These capacities include not only exhibitions, studios, and access to buyers, but also exposure to the media, research, and publications. In a way, I am claiming that institutional representation is systemically consistent with the inconsistencies of civil society.

You will ask what does this have to do with Madolo specifically but this observation, however irrelevant it may seem definitely needs more exploration into how artists who have largely existed on the margins of institutional representations have faired in the post-apartheid condition. What sort of improvisatory practices and innovative strategies have come up because of the constraints that have been engendered by institutional under-representation? Do these impact on the morphology of work artists explore?

Madolo studied at Walter Sisulu University, where he graduated with a National Diploma in Fine Arts. Though born and raised in the small rural town of Alice, Eastern Cape, the urban space has become the running theme in Madolo’s work. Madolo seems to be now primarily vacillating between his collage works and oil paintings. The paintings exhibited in his studio are largely figurative and portraits—both individual and group portraits, with some of them commissioned work. In these works, Madolo seems to take a more studious approach that is exploratory but also keeping with the style of figurative accuracy. The kind of staccato laying and texturing of paint he’s developing in these works is certainly still naive but nevertheless honest and eager to push the materials without losing his brief. Considering the type of clientele that would commission these portraits, it seems, one has to keep the exploratory path consistently in check.

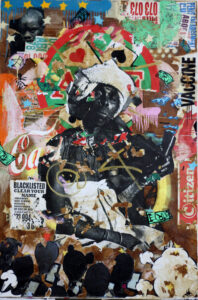

Ace II

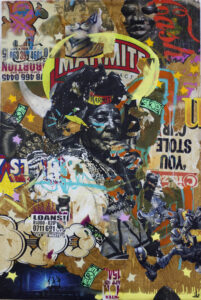

Then there are the collages. It is with the collage work that Madolo is increasingly making his mark in the contemporary art scene. In fact, beyond his two-toned scattered works on cityscapes, it is these collages that truly depict his fascination with the city. As alluded before, the history of collage is tied to the history of the industrialisation that reconfigured the city and our modes of seeing. By its use of non-traditional visual materials such as pieces of paper, photos, texts, and other related visual media, the art of collaging (or montage rather) constructs a singular image by juxtaposing different pictures. Visually, the montage breaks the illusion of reality and perspective by reconstructing our ways of bearing witness and engaging with the physical world. Madolo’s takes on the city, particularly the lower-income parts of the city’s walls, as sites of witnessing what it has to offer, visualises, and testifies to. These would range from small business advertisements, to posters, to random inscriptions that are haphazardly arranged, pulled off and new ones superimposed over the older ones.

Formally, Madolo uses the technique of montage to not necessarily reproduce but reorient the city wall’s visual template and constitution. In certain instances, he would prime his background with coffee to help bring the chromatic illusion to gesture to the unhygienic nature of these neighbourhoods. These montages all have a similar serial pictorial structure, that is, they use photographic portraits of black people’s faces or figures at the centre of the piece as a kind of totemic presence. It is not very clear what the conceptual purchase of this centrality is, at least not now, but one can certainly go out on a limb and say that this might be an attempt for us to differently reckon with a presence that ordinarily enters the frame as alterity. He then builds around this face or figure, by pasting, painting, spraying, annotating, taring and so forth, through different pieces of paper, typically advertising popular brands and imagery to give a visual impression of the walls and their signifying properties. The importance of how brands exploit and over familiarise themselves as standards in low-income communities is another issue that informs or forms part of the works’ general commentary.

Marmite IIV

The totemic centrality of these largely unknown figures, both iconises them as well as inverts the logic of iconicity. If the icon is generally a figure worthy of veneration through which photographic over-representation establishes its importance, Madolo’s work cuts through this. His figure of “racial iconicity,” to use Nicole Fleetwood’s work, takes seriously the ordinary black (poor) people and their worlds. According to Fleetwood, racial iconicity hinges on the tension between the veneration and denigration that have been critical anchors in the development of a black culture. In certain instances, for example, with Marmite, the icon is a rural Xhosa woman in her traditional garb smoking her pipe. The relationality between the African female and the Marmite (dark savoury paste) aren’t exactly clear, but we know that historically the African female was quintessentially regarded as a figure of the undesirable. Interestingly Madolo has maintained in one of his interviews that at the base of his work, is what he calls “classism.” By classicism, he means racial discrimination as a form of classificatory practice.

Nevertheless, the kind of work that is coming out of the contemporary scene in South Africa, though at times it does not necessarily have an immediately political and explicatory narrative and yet the overall gestures remain, can be thought-provoking and generative at the level of its formal quality and commentary. The role of art writing, it seems to me, now more often than not, is to try and cull these indirect innuendos and suggestions out of these works. Mncedi Madolo’s work has so much room for growth and so much incredible potential to explore the mediums, subject matters, and materials in ways that will truly enrich his work. If one has time, please do visit his studio at Ellis House Art Building or search for his work online to make your own judgment.