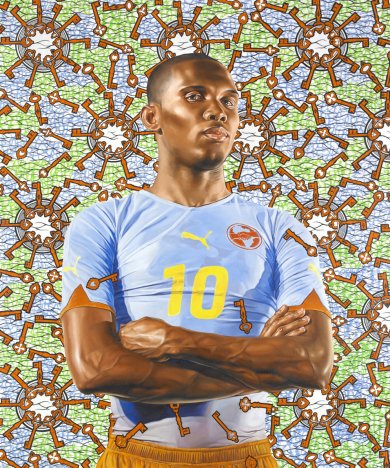

Like other black artists – Robert Colescott is an early example – he tries to put black people into the overly white, male, Western art history. He starts from known ‘masterpieces’ in which saints, kings, generals or dandies are portrayed. He replaces the ‘models’ and puts young, beautiful, trendy black guys in it. His paintings are often big, always painted in an almost painfully realistic style, but they don’t have anything to do with reality. They portray an ideal reality, a lavishly decorated reality, a golden reality, a kitschy reality, the reality of a gay man who likes to go over the top, who likes to pose as the creator of a dream.

Rob Perrée on Kehinde Wiley in his ‘New York Diary’.

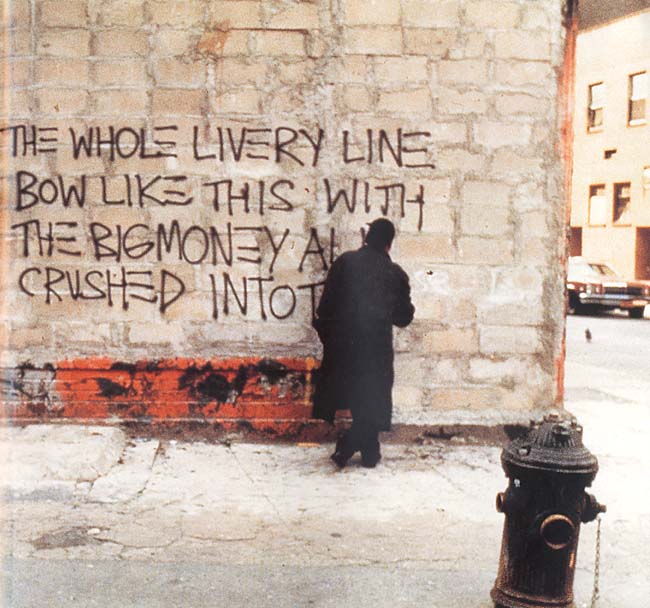

Wangechi Mutu, from the ‘A Fantastic Journey’ exhibition.

NEW YORK DIARY

Ten days of wandering around wondering

Day 1

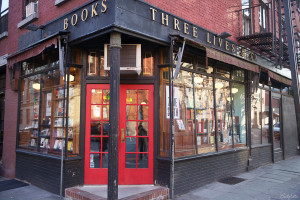

It doesn’t change. Every time I come back in New York, my first appointment is with the bookshop. THE bookshop is ‘Three Lives’ of course, a small living room kind of bookshop in the Village. Barnes and Nobles has a lot, but I never find what I like, in ‘Three Lives’ they have a limited amount of books but the selection is made by people who like to read, not by people who want to sell. That makes a big difference. Michael Cunningham – author of ‘The Hours’ – calls it “one of the greatest bookshops on the face of earth”. And he is right. Customers talk about books there, writers go in and out, every month there is some type of reading. You end up buying books that you didn’t even know were published.

With a memoir of writer Brad Googh and a little book with short stories of Tennessee Williams I leave the shop smiling. I am ready for New York again.

Courtesy, the artist.

Courtesy, the artist.

Day 2

From the first day on the Kehinde Wiley exhibition in the Brooklyn Museum is talk of the town. You either love his work or you hate it, but everybody has to have an opinion about it. He has been working as an artist for at least 20 years, but the last couple of years he is becoming vey successful. Like other black artists – Robert Colescott is an early example – he tries to put black people into the overly white, male, Western art history. He starts from known ‘masterpieces’ in which saints, kings, generals or dandies are portrayed. He replaces the ‘models’ and puts young, beautiful, trendy black guys in it. His paintings are often big, always painted in an almost painfully realistic style, but they don’t have anything to do with reality. They portray an ideal reality, a lavishly decorated reality, a golden reality, a kitschy reality, the reality of a gay man who likes to go over the top, who likes to pose as the creator of a dream. I forgive him. He dares to be grotesque, he dares to be outrageous, he dares to be controversial. A rare quality in the arts.

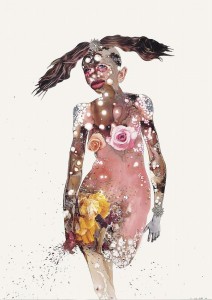

What a contrast with the other exhibition in the same museum that also drew my attention: ‘Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks’. A collection of pieces of paper with notes on it, remarks, just words, references etc. dressed up with a couple of his famous word paintings and painted objects. Of course, one could criticize the curators for trying to make everything that Basquiat made or wrote into an art work. Not every shopping list is a masterpiece, there is nothing wrong with painting over a casual doodle on the wall of a bathroom, but strangely enough the notes that are shown in this exhibition give you a better understanding of his work, of the references he used in his paintings and drawings. And, then it becomes all the more clear, his words have a high image quality. He paints words, which is more than just writing words.

In both exhibitions a lot of young black people were crowding the rooms. That’s rare too.

Day 3

It took 7 years but this week the new Whitney Museum of American Art, designed by Renzo Piano (78) – he is the creator of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, to mention one of his controversial buildings – opened its doors. It is a wonderful building, not so much in the sense of beautiful but it is highly functional, very user-friendly, very art-friendly, in a first class location – in the meat packing district near the Hudson – with amazing views. The rooms are spacious and on three of the floors go into an outside terrace. The building is not intimidating like many museums can be. I felt comfortable from the first moment on. It is a place where you want to go even if there is nothing of interest to see.

‘America is hard to see’ is the inaugural exhibition. An interesting and clever selection from the collection. Many female artists were chosen – a huge and stunning Lee Krasner for instance – and the amount of African American artists looked almost like a statement. Romare Bearden, Glenn Ligon, Kara Walker, Mark Bradford, Jean-Michel Basquiat, David Hammons, Jacob Lawrence, Dread Scott, to name a few.

The meat packing district turned into a very luxurious part of New York. It is not an area where you can go for a quick bite after your museum visit. Unless you are loaded. That’s the only disadvantage I can come up with for now. My hamburger + drink was $40,-. Without tip. With regret.

Eye Spy (Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York).

Eye Spy (Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York).

Wangechi Mutu gave a lecture at the New School in the afternoon. She is originally from Kenya, but she moved to New York about 20 years ago. I first met her and her work in New Orleans, just after Katrina, in ‘Prospect 1’. She presented a touching installation in the 9th Ward, which was the part of Orleans that suffered the most of Katrina. Many people died there or lost everything they owned. She had built the steel frame of a house with a rocking chair in the middle. Nothing else. The sober installation referred to the story of an old black woman who had survived the disaster but had lost her house. Because the insurance company did not want to pay anything she was forced to leave the city after all. Mutu erected a monument to her. More than a year later I had a long interview with her in her Brooklyn studio. So, attending her lecture was a logical step for me.

She gave an interesting overview of her work, of all the references and the problems she faced when she moved to the US to become an artist, leaving her family and friends behind and taking her different culture with her. Most of the room was filled with admirers, mainly young women. She is, obviously, not only a great artist but also a excellent role model.

Day 4.

I am preparing my lecture for the ‘Black Portraiture’ conference at the end of May in Florence. In the evening I have a dinner with friends in Harlem. No art today, a lot of art talk though.

1921 (Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery New York).

1921 (Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery New York).

Day 5

Hank Willis Thomas shows his latest project at Jack Shainman Gallery in Chelsea. ‘Unbranded: a century of white woman, 1915-2015’ is the title. He has reproduced 100 printed advertisements and unmoored them from their commercial context. No brand names, no slogans. It becomes an intriguing and sometimes hilarious history of white women’s stereotyping, of interpretations of desire, of commercial strategies, of racial bias, of the rise and decline of printed advertising, of kooky worldviews and of photography as a medium. Because the photos have different seizes it looks as if Willis Thomas has put his visual history on music. Elevator music, to be precise. A great show. (see also article of Shelley Rice and interview of Deborah Willis in this edition of Africanah.org)

After my visit to Chelsea I meet with Emmanuel Iduma in a French restaurant in the Village (New York has many restaurants, but hardly any (grand) cafés). He is one of the writers for Africanah.org. It feels uncomfortable for me to work with colleagues without meeting them. I like to know who is ‘behind’ the text. Since we both happened to be in New York we could work out that ‘problem’. Iduma is from Nigeria but moved to the US a couple of years ago to follow the MFA program in Art Criticism & Writing at SVA (School for Visual Arts). He writes fiction and art criticism. He published the novel ‘Farad’ and was co-editor of ‘Gambit: Newer African Writing’. He is a member of the group ‘Invisible Borders’. They won a Prince Claus Award in 2014 and are participating in the Venice Biennial 2015.

The website of ‘Invisible Borders’ explains what the group is about: “Since 2009, Invisible Borders Trans-African Organization has organized road trips from Lagos to other parts of the African continent. It forms a central premise in the Organization’s attempt to promote an idea of trans-African exchange, within and on the margins of the contemporary art world. For each iteration up to 10 artists are invited to participate, artists who work in different mediums. Beginning as a photography initiative, the project has embraced other disciplines, notably literature, film, and performance art. While on the road, the participating artists and the organization make a point of sharing real-time photographs, factual and reflective blog posts, as well as video diaries.”

His experience as an immigrant is similar to the experience Wangechi Mutu was talking about this week. All in all an inspiring conversation with a talented and committed writer.

He will continue submitting personal texts to Africanah.org.

Copyright New York Times.

Copyright New York Times.

Day 6

There was a time, not even long ago, that you really had to carry the Sunday New York Times home. About 2 kilo’s of reading. Enough to spend a whole rainy or otherwise boring Sunday. That is not the case anymore. Like other quality newspapers – The Wall Street Journal and The Guardian – the New York Times is trying to survive. It fired many good journalists and it reduced the budget for research journalism dramatically.

However, in this weeks NY Magazine was an interesting report from a project of the French artist JR (his identity is unconfirmed). Commissioned by the NYT he has photographed recent immigrants. The larger than life portraits he printed on stock paper. Then he photographed each subject again outside, on the street, “holding up that magnified self”. He walks with the paper immigrant through the city. “To be an immigrant is to have moved”, he said, “to be a New Yorker is to keep moving.”

In 2002 Robert de Niro and a few of his friends, living in TriBeCa, Lower Manhattan, started the TriBeCa Filmfestival. As a response to September 11, to give back vitality to that part of the city and to turn New York into a filmmaking center. From the beginning on I have tried to get tickets for documentaries on artists or art topics. This year there was not much of a choice. One documentary stood out: ‘Peggy Guggenheim. Art Addict’, directed by Lisa Immordino Vreeland. It proved to be a great documentary. Peggy Guggenheim was the black sheep of the wealthy Guggenheim family. Her life was full of turbulence, but also full of art. She collected in a very early stage works from Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Max Ernst, Salvador Dali, Mark Rothko, Giacometti and many others. She slept with a lot of these artists. “If you sleep with him first, the price of the work will be lower” she says in an interview that was used as the leading thread of the film. In her collecting, but also in her emancipated behavior, she was ahead of her time. Her uncle, who took the initiative for the founding of the Guggenheim Museum, did not want her collection in it. He called it trash. That trash is now worth billions. The combination of unique footage – film fragments of for instance Picasso, Cocteau, Brancusi – and her lively voice (taped one year before she died) made the documentary funny as well as sad, in many ways special. It will be internationally distributed.

The Great Migration.

The Great Migration.

Day 7

In 1940 Jacob Lawrence painted ‘The Great Migration’, the mass movement of African Americans from the rural South to the urban North. It took him a year. Sixty small panels tell the story. Every panel you can consider a scene in that amazing story. An additional text explains every scene. Lawrence style is figurative in a bold, elementary way. He does not paint in detail, his people don’t have clear features let alone their own character, his environments don’t have an identity. ‘The Great Migration’ is more important as a historical project, a story that had to be told, more so for the ‘actors’ in it, than an artistic performance (Lawrence was a starting artist. He was only 23 when he finished ‘The Great Migration’). Lawrence called the 60 paintings “a portrait of myself, a portrait of my family, a portrait of my peers”.

Strangely enough, the series was in the collection of 2 museums: the MoMA and the Philips collection. I don’t know why Philips only got the odd numbers and the MoMA the rest. Was it money? Was it Lawrence struggling with loyalty? In this MoMA exhibition they are reunited. It struck me that the paintings are so small. I only knew them from reproductions in books. The modest size added intimacy to the story though.

More and more I realize that this diary is dominated by the topics of migration and immigration.

Photo/Copyright Paul Fusco

Photo/Copyright Paul Fusco

Day 8

I meet artist and activist Eve Sandler in the Upper Westside. We talk about the killings of black men by the police. “It is not new, it is only because of the social media that it looks as if it did not happen before. It is good that the social media bring it to the attention of white people. Many of them did not realize what is going on.” Eve Sandler formed the group ‘Women in Mourning and Outrage’ in 1999. The reason was the killing of a young Muslim Guinean immigrant in the Bronx. Four white policemen fired 41 bullets at him, 19 hit their mark. The women appeared as a group at rallies. They dressed in black, wearing veils. They performed in silence, with dignity. They held photos of Darrio, the victim. Because they operated as a group avoiding violence, the police did not know what to do with them. They more or less disarmed the police. For two years the ‘Women in Mourning and Outrage’ repeated their performance on locations where it was necessary. “It was sometimes very scary. It happened that we were in between the police and the protesters knowing that police snipers were on the roofs surrounding us.”

Eve Sandler was one of the artists in my exhibition ‘Postcards from Black America. Contemporary African American Art’ (1998-1999). She showed ‘The Wash’, a touching multi media installation. The work was about the shocking experiences of her grandmother. Parts of the narrative were projected on laundry, hanging from the ceiling.

Born in Ghana, moved to London, lives in Paris.

Born in Ghana, moved to London, lives in Paris.

Day 9

My stay ends with a musical performance in Brooklyn. Benjamin Clementine, a singer from Paris of African descent visits the US for two performances in New York. He was a street musician. You could hear him in subway stations and on street corners in the French capital. There he was discovered by a clever producer. The rest is history. He got the chance to make a compact and made his entrance, almost overnight, into the European hall of fame. It sounds like an all American success story.

The concert was great. A mix of Satie, opera and pop. He has a voice that can go all the way up and down. One moment he screams, the next moment he whispers. The songs are unpredictable, as if he is improvising all the time. The lyrics are close to poetry. His performance is made up shy. I don’t know if America is ready for him, the audience in Brooklyn was.

Day 10

I fly back to Amsterdam.