Toni Morrison (1931-2019) was one of the most important American writers. She inspired many fellow authors and also artists. She won the Nobel Prize for Literature and emphatically made her voice heard in discussions about race, feminism and Black Lives Matter. She was a novelist of the black experience.

Sarah Ladipo Manyika had the chance to meet her. In this article she gives an extensive, personal report of her meeting.

On Meeting Toni Morrison

I.

“Here is the house.”

Toni Morrison, The Bluest Eye, 1970.

The house commands a view. Square and solid, it sits on an embankment rising from the Hudson River. Meticulously maintained, its clapboard sidings and balcony railings are painted in shades of tan and river grey, with an ivory picket fence around the perimeter. The entrance is on the side of the house, hidden from public view. The door opens and a woman who says she is Nadine lets us in. I’ve come with Mario Kaiser, friend and writer, who has arranged this interview with a German magazine. Nadine leads the way downstairs to the study and announces us.

Ms. Morrison is dressed in black—trousers, caftan, woolen cap—and seated opposite a woman whose back is towards us. This other woman is a journalist and asks us if we can give her more time. We look to Ms. Morrison, who seems to sense our concern. “I’ll give you all the time you need,” she says. “Just make yourself at home.”

Back upstairs, Nadine is frying onions and peppers which sends out a comforting smell of any number of cuisines that I love. The aroma from the kitchen has me thinking of food in Ms. Morrison’s novels and how she often uses food to hint at what simmers beneath the surface. There’s the smoke curling from the soft white insides of biscuits in Beloved (1987), the terrible crash of Mrs. Breedlove’s berry cobbler in The Bluest Eye, the hastily abandoned vegetable chopping in Paradise (1997). In God Help the Child (2015), her most recent novel, Queen prepares a “united nations” soup which tastes like “manna.” I imagine the soup smelling like Nadine’s cooking. “Something healthy for Mrs. Morrison,” says Nadine, who is from Jamaica.

Ms. Morrison has said make yourself at home. I glance at Mario, whose look of concentration is befitting of the award-winning writer that he is. Meticulously, he writes in a reporter’s notepad, while my gaze darts from kitchen to living room to the deck jutting out over the Hudson. A flock of seagulls transports me to the opening pages of Jazz (1992), then to Ms. Morrison’s Nobel Prize Lecture and her parable of an old blind woman. In this parable, several children have come to visit the blind woman, thinking they can test the limits of her wisdom. One asks, “Old woman, I hold in my hand a bird. Tell me whether it is living or dead.” The woman is silent for a long time before she finally speaks:

“I don’t know,” she says. “I don’t know whether the bird you are holding is dead or alive, but what I do know is that it is in your hands.”

*

The bird becomes a metaphor for language and the story, a profound meditation on the complex truths surrounding narrative—its dangers and its power. Have we thought hard enough, deeply enough, about the questions we are about to ask this 86-year-old writer? Will we be able to go beyond the limits of questions and answers and gain wisdom?

*

As we wait for Ms. Morrison to receive us, and I’m trying to take in what surrounds me, I reach for a photograph album. Such albums were ubiquitous in my Lagos-Jos-Nairobi childhood, so I smile at the familiarity of posed, family shots, flicking through wedding photographs of Ms. Morrison’s eldest son, Ford. Later, I will wish that I had breathed more deeply, more slowly, had taken in more details of the home, the books on tables, and the memories in the pictures.

What I do remember is that the ceiling, walls, and carpet of the living room are all subtle variations of the dove-grey Hudson river they overlook; that light pours through the windows on all sides; not a bright light, but enough to give the room an airy feel. The warmth comes from the kitchen. Someone has thought carefully about the home’s furnishings—understated, modern, and contemplative, with accents from Africa. A Dogon figure, an Akuaba fertility doll, and a small Shona sculpture are all on display. And on the wall above the Shaker-inspired stairs leading to the top floor hangs a prayer board, reminding me of one of Victor Ekpuk’s decorative pieces which are fast becoming collectors items. I smile, feeling at home; this is simultaneously Kingston, Accra, Lagos, Harare and New York. I wonder if Ms. Morrison has ever visited the African continent. Nan in Beloved arrived in America “from the sea,” speaking a language that was not English. Would Ms. Morrison ever write a story set in Africa? And if so, what century would she set her story in? What would she say about slavery on the motherland?

*

Ms. Morrison’s other interview has finished; I hurry to use the guest bathroom. Even though I know I must be quick, I linger in the bathroom adorned with photographs of Ms. Morrison and other writers that I’ve long admired—Soyinka, Marquez, Baldwin. In the spot above the sink, where I’d hoped for a mirror, hangs the letter from the Nobel Prize Committee announcing its decision to award Professor Toni Morrison its highest honor. On the opposite wall hangs a “Publication Denial Notification” outlining why Ms. Morrison’s novel Paradise was banned from Texas correctional facilities for fears of “inmate disruption such as strikes or riots.” I smile at where the letter hangs, just above the toilet, thinking I might do the same with the copy of a recent school letter that has deemed my first novel “morally distasteful” and called for it to be banned from Nigeria’s school syllabus. Ms. Morrison’s letter is placed above the toilet’s April Fresh air freshener, under a photograph of Muhammad Ali. Ali famously boasted of wrestling with alligators, handcuffing lightning, and throwing thunder in jail. Ms. Morrison was once his editor; I hear she wrestled him to the page.

*

Of the downstairs area where we return to talk to Ms. Morrison and where she tells us she writes, I remember almost nothing except that on the table between us, next to our water glasses, lay a copy of Mohsin Hamid’s, Exit West (2017) which she had yet to read and I had just read. At first, I was conscious of the house noises that interrupted the flow of our interview, especially the shrill pinging sound each time the front door was opened. There was also the intermittent clatter of Nadine’s pots and pans and her footsteps overhead, but in the presence of Ms. Morrison, these noises soon fade. For the two hours that she generously grants us, my attention is fixed on her, the softness in her gaze, the light freckles on her hand, but above all, on the sound of her voice, that voice.

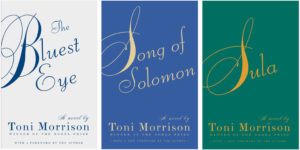

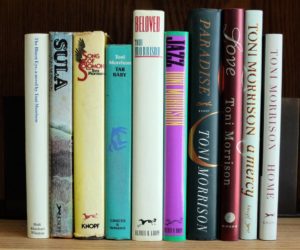

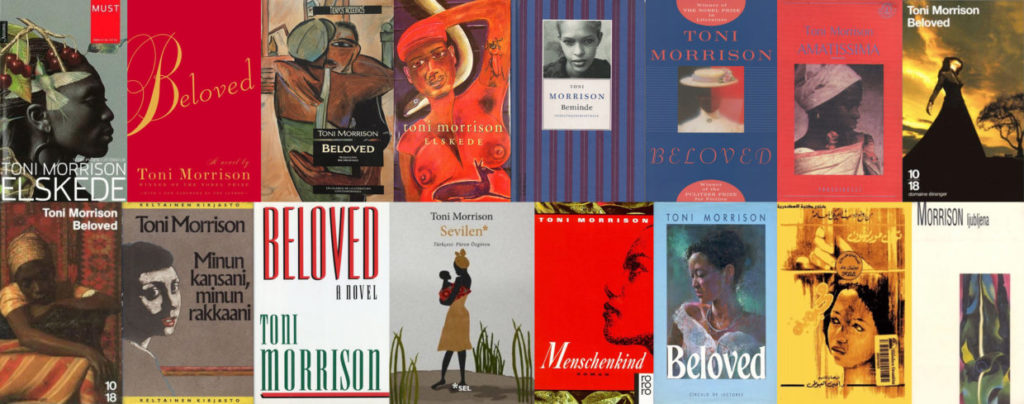

These first editions of Morrison’s novels are among the Toni Morrison Papers, housed in the Manuscripts Division, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library. (Photo by Don Skemer, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections)

II.

“Once upon a time there was an old woman. … Her reputation for wisdom is without peer and without question.”

Toni Morrison, Nobel Lecture

For weeks, I had been wondering what she would be like. It was one thing to have encountered Toni Morrison through her writing and to have watched her lectures and interviews but another to meet her in person. Having just written a book about a 74-year-old woman, I am curious to see what Ms. Morrison reveals about her experience of older age. I had heard that she is wheelchair-bound and often in pain. I hope she won’t be in too much pain (any pain) on this day.

*

The first thing that strikes me when I meet her is that she looks like one of my friends. You know that feeling when you see someone and think, “Wow, this person is just like so-and-so!” Ms. Morrison has the same light complexion, wide-set eyes, and thick hair as my friend, the documentary filmmaker, Xoliswa Sithole. All but one of Ms. Morrison’s silver-grey locks are hidden beneath her beret. The lone lock pokes out, resting on the nape of her neck. But it’s her presence, more than the physical resemblances, that most reminds me of my friend, making her feel familiar. She exudes confidence from an erect and still posture, from her large stature. She is regal even when, as she occasionally does, dabbing at a watering eye.

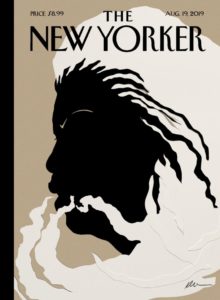

KaraWalker, Quiet as It’s Ket, 2019. courtesy The New Yorker

I begin by asking how should we address her. Does she prefer Professor, Doctor, Mrs., or Ms.? “I like Toni,” she says, smiling. Her smile portends a playfulness and openness that will remain one of my lasting memories of our conversation. Twice during the interview, we are interrupted by friends or family, and on each occasion she will introduce us as “friends.”

*

I’ve known of Toni’s sense of humor both from her books and from watching interviews, but I’m surprised by how much she will make us laugh. She frequently jokes about herself and sometimes about others. Occasionally, she does both simultaneously such as when a friend drops by with Easter flowers and has to squeeze past us to give her a hug. “You’re too fat, you’re like me!” she exclaims. This ability to joke with others and laugh at herself not only reminds me of people I’m most fond of, but it’s a trait that I most associate with Nigerians. Toni is also prone to laughing at moments that are sometimes the opposite of funny, and this too feels familiar, as a mechanism for enduring what is otherwise traumatic. I claim Toni as an honorary Nigerian and she may well be, originally—Igbo, Yoruba, or any of the many ethnicities that make up Nigeria. Like a true Nigerian, she is also fond of exaggerations. She talks of publishers who “beat you up” over titles and boasts of a great-grandmother, Millicent who, she says, is probably “still alive.” Toni is not bitter in her old age, which was something I’d wondered about while reading God Help the Child and sensing cynicism or, like the old woman in her parable, just keeping her distance from younger generations. On this day, at least, she’s not bitter.

*

Toni’s humor and playfulness are magnified by her love of theatre. As an undergraduate at Howard University she belonged to a traveling theatre group. She speaks fondly of this time, telling us that if she could, she’d like to return to those days. As she talks, she becomes like an actor on stage. She uses silence, shouts, songs, cursing, recitation, and fake-crying, all to great dramatic effect. At one point, she takes a long pause before launching into the retelling of a ghost story told to her as a child. Half cooing, half singing, she begins: “Gonna whop, gonna chop my wife’s head off! … Tam-tam, tam-tam, tam-tam-gonna cut my wife’s HEAD OFF!” Toni is such a thespian that I find myself ineluctably drawn in with “umh’s” and “ahh’s” as if in call and response, as if in church, as if I’m in Nigeria where respect and appreciation for an elder is vocalized in variations of “ehe-ehe,” “oo,” and “yes, ma.” Her theatricality also causes me, without realizing it at times, to mimic the cadence of her voice and her accents.

When I ask what President Obama whispered to her after presenting her with the Presidential Medal of Honor, I play the role of co-conspirator adopting her American accent in anticipation of what she’ll say next, only to be surprised when she says she doesn’t remember. “I knew then!” she explains, “But soon as I left, I thought: What did he say? I was so embarrassed!” Trying to make her feel better, I joke that she can make it up. Little do I know that the story is only just beginning. Masterfully, she weaves a longer story, revealing only at the end that her son later asked Obama if he remembered what he whispered to his mother. Obama said, “Yeah, sure I remember. I said, “I love you.” Toni knew all along.

As a writer, I’m particularly drawn to Toni’s choice of words. She is fond of interjections, exclamations, repetition, and made-up words. Toni-isms, I shall call them. “Pank,” she says mimicking the sound and action of switching off the T.V. whenever President Trump appears (a man she never calls by name but as “this so-called president”) and “Google-shot” when referring to the use of Google Earth to view a location. Sometimes she speaks in a childlike voice, sometimes in a stern voice, sometimes she trails off at the end of a sentence on the cusp or middle of thought, poised before diving into deeper thought. What is particularly fascinating for me is recognizing in her speech many of the same rhythms and phrases that she uses in her writing. She sounds like Frank Money in Home (2012) when she says: “I want you to know,” “You have no idea,” “Think about it,” and in that voice.

*

I’ve read that writing and being a mother are the two things that matter the most to Toni. As a mother of a son, I’m curious to know about her experience of motherhood and how she balances the two things. A large, glass-framed photograph of her youngest son, Slade, hangs by the front door. This is the son who died of cancer, and when we ask if there are things she would like to bring back from her past, it is Slade she mentions first. I feel pain for her. How does any parent cope with the death of a child? I wonder how it has affected Toni’s relationship with her remaining son, Ford, whom we are lucky to meet. The interaction between mother and son is warm and playful. Toni takes great pride in Ford, and he in her. “Whadya bring me?” she asks as soon as he arrives, “a sam-wich?”—to which he responds that he’s brought her books. She is writing a new book and is especially excited by a book about Richard Nixon that he’s brought for her new project. Ford is polite and kind and takes no umbrage when his mum bosses him around. “Take that book from here!” she play-shouts, instructing him not to clutter the area where we’re sitting. Our laughter, like in Tar Baby (1981) is “sprawling like a quilt over the command.”

This is Toni. Mother. Nobel Laureate.

III.

“Berries that tasted like church.”

Toni Morrison, Beloved

Toni Morrison begins her first novel The Bluest Eye with several paragraphs worth of lines written in the style of the best-selling “Dick and Jane” children’s books:

Here is the house. It is green and white. It has a red door. It is very pretty. Here is the family. Mother, Father, Dick, and Jane live in the green-and-white house. They are happy.

*

In Nigeria, where I learned to read, the equivalent primers (courtesy of Nigeria’s former colonial masters) were the “Peter and Jane” Ladybird books with the same stock white characters and no black characters. Both Janes were blond. So, even before reading Toni Morrison’s work, or knowing about the society she was writing about, I understood what it meant not to find reflections of oneself in literature. When Toni says at the beginning of our interview that she is “writing to, about, and for other black people,” and that she writes about black people because she finds us “interesting,” I cannot help but respond with a resounding “Yes!” F.U.B.U. as Solange sings—For us by us. This is why I often quote Toni Morrison who has said that if there’s a book you want to read but cannot find, then you must write it. This is what compels me to write.

*

The first Toni Morrison book that I bought was Jazz. At the time, I knew little about the author or her standing in the literary canon, but I was drawn to the book’s title. It sounded “real cool” to me in my “Jazz June” days, as Gwendolyn Brooks puts it. I was twenty-something, with little exposure to literary fiction and only superficial knowledge of the history of black people in America. I knew about the history of West Africa and had some textbook knowledge of the Atlantic slave trade, but no deep understanding of the scale or lived horror of slavery, and virtually nothing of the legacy of racism in America. The images I saw of America on T.V. were ones that made America look happy and prosperous. African Americans, I assumed, led lives like the Huxtables from The Cosby Show. Reading Toni Morrison was the beginning of my education on America then and now, black and white.

*

As soon as I started to read Jazz, I knew that the sound of Toni Morrison’s stories mattered. Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., renown literary critic and historian, refers to her novels as “talking books,” and just a few days before our interview, he encouraged me to ask her about this. I love the phrase “talking books” which harkens back to the talking drums of my childhood. And even before we ask her about the oral tradition in her work, Toni tells us: “I like the act of reading my works because I measure their value in terms of how they sound.” I’m elated to hear this as the sound of stories has always been very important to me as reader and writer. I also prefer listening to Toni narrate her own audio books before I read them. Never before have I heard a writer state the importance of a book’s sound so explicitly, and certainly never a Nobel Laureate. It makes me question why the literary establishment continues to privilege text on the page over the orality of read-aloud prose.

*

As Toni expands upon America’s legacy of racism and skin privileges, I am struck, as I was when looking around her home, by the interconnectedness of history. There are many similarities between America’s civil-rights era and apartheid Southern Africa. When she mentions Hecht’s, the only department store in Washington D.C. where colored girls of her generation were allowed to use the restroom, I remember my husband’s stories of not being able to try on clothes in Rhodesia’s department stores, not being able to use white-only restrooms, not even being able to use the main elevators. Black people either took the stairs or, for the tallest buildings, used the service elevator in then apartheid Rhodesia.

Toni’s discussion of the importance of names and naming in her work also resonates. Names and nicknames matter within the African American community just as they continue to matter within the African continent. I have recently been reminded of this through exchanges with students in Nigeria who study my novel In Dependence (2008) for the university entrance exam; students with names such as Favour, Happiness, Precious, Marvelous, and Godswill. Toni has these wonderful names too, each of which signifies, often ironically, something essential about the character. In her family, nicknames, she tells us, were “usually about your weakness. Whatever your weakness is, that’s what they call you. So you can get that out of the way right away.” In God Help the Child, she names her characters Bride, Brooklyn, Queen, Booker, and Sweetness. Bride is no Bride and Sweetness is not sweet. In her forthcoming book, Justice, Toni tells us about a “horrible slave owner” called “Goodmaster” who insists that his slaves take his name as theirs. I wonder if Toni has read NoViolet Bulawayo’s novel We Need New Names (2014). which celebrates names with characters such as Darling, Bastard, and Godknows. Morayo, the adventure-loving protagonist of my most recent novel, means “I see joy” in Yoruba. In each case, the naming captures something essential about the character, sometimes opening the door to irony, but always making them memorable.

Then we get to sex. “Can we talk about sex?” I ask. “Yeah,” she smiles, “I’m in a good position to talk about it, since it’s been like a thousand years. What do you want to know?” Writing about sex is notoriously difficult. There’s even a well-known prize—The Bad Sex in Fiction Award—that ridicules how badly it can be done. How then does Toni do it so well? She tells us that it’s not the clinical descriptions that make for good writing about sex (or indeed sex itself); rather, it’s how to associate sex with something else, something surprising that makes the writing about sex more interesting and more compelling. A linguistic agility with metaphor is a hallmark of Toni’s language. One of my favorite lines comes from Beloved, from the scene in which the ferryman, Stamp Paid, having helped Sethe cross to freedom, goes to the river’s edge in search of blackberries. These berries, we are told, “tasted so good and happy that to eat them was like being in church. Just one of the berries and you felt anointed.” Much is conveyed in the startling juxtaposition of berries with church—much that speaks not only to the storyline but to the history of slavery, to America’s history, to salvation, exaltation, and ecstasy.

*

The history of slavery and its legacy is so horrific that I wonder how Toni manages to write about slavery and persistent racism without the heavy weight of this history collapsing her stories. How does she remain sane when writing about horrors that have not ended? How is she able to write about racism in America while, as James Baldwin put it, keeping her heart free of hatred and despair? How does she hold on to hope? I ask her how she strikes the delicate balance in her writing between memory and forgetting—forgetting in the sense of needing to heal, which is a sentiment frequently voiced by characters in her novels. Toni’s response to my question, as with many of her responses, goes beyond what is asked, to what, like the children in the parable, I’ve dared not ask. What’s required, she replies, “in order to get to a happy place—what I call happy, even though people are dropping dead all over my books—is the acquisition of knowledge. And if you know something at the end, or toward the end, that you didn’t know before, it’s almost wisdom. And if I can hit that chord, then everything else was worth it. Knowing something you didn’t know before. (…) It’s not the battles,” she adds, “A lot of books are about winning something. I’m not interested in that so much as the way the intellectual life and the emotional life should be.” Hearing this is one of the many moments when I feel grateful that we are recording our conversation so that I can return to it to re-listen and learn something new each time I listen. For now it’s this, that what matters both in life and in stories, is wisdom. The emphasis, thoughtfully illustrated in her Nobel lecture in her parable of the old woman, is on how hard we must try and how hard language must work. “Language can never ‘pin down’ slavery, genocide, war. Nor should it yearn for the arrogance to be able to do so. Its force, its felicity, is in its reach toward the ineffable.”

*

Before we leave, I ask Toni if she will sign my son’s copy of The Bluest Eye. It’s his favorite book, and he’s asked me to ask how she finds the language in which she writes. “Tell him I’m a genius,” she replies, smiling. And we laugh and laugh.