In her Flowers Series, Gabonese artist Owanto reminds us of how the colonial lens could sometimes go as far as invading vulnerable moments during a female initiate ceremony. One imagines a stranger looking on, into an age-old ritual and capturing private moments created to define womanhood. One wonders if that gaze leaves its own kind of mark, a scar that deeply diminishes the girls’ dignity.

Tandazani Dhlakama on the Flowers Series of the Gabonese artist Owano

Flowers that Mask and Heal

A Look at Owanto’s Flowers Series

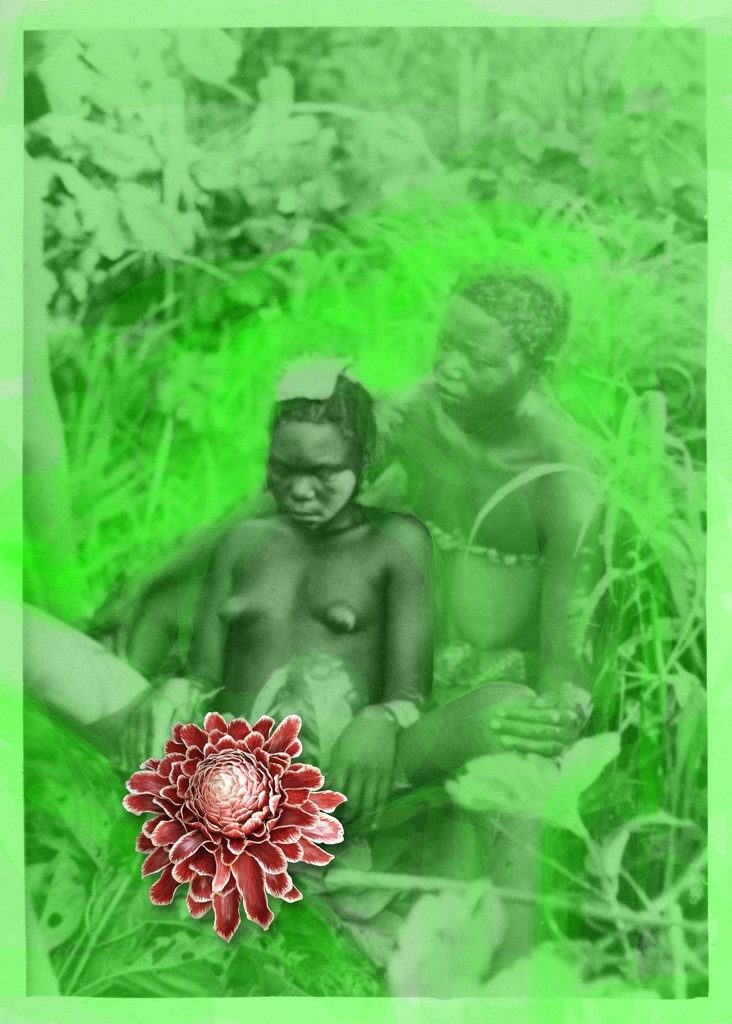

Two somber adolescents sit somewhere in an unknown forest. We cannot tell if the other is comforting her companion by gently holding her, or if she had been forcing the other’s knee up during the procedure. Perhaps she has been doing both. The artist has veiled the girls in opaque green paint and shielded viewers from the affliction caused by the cutting. She has done this by positioning a large porcelain flower over the wound that lies between the thighs.

Flowwers IV, 2015, courtesy the artist

In a myriad archive around the world lie photographs of African bodies laboring, performing rituals, posing as instructed and starring back. These photographic archives represent a time when images were unapologetically used to justify expansion, commercial enterprise and discriminatory discourse.

Susan Sontag was correct when she likened the camera to something that intrudes. (1) From these archives, one learns that the colonial lens often degraded and dehumanized, observing royal clans and dynasties and reducing them to mere specimen. This lens was infatuated by ceremony that it deemed exotic and mysterious. It scrutinized how the subjects danced for rain, for harvest, for love and for war. It brazenly disregarded spiritual sacraments by gawking on as the bodies honored ancestors through trance and offerings. It captured initiation processes that formulated the chore of identity. It documented sacred rites which signified passage from boy to man, girl to woman, woman to mother, commoner to chief and single to betrothed. It examined how the bodies moved to the rhythm of life’s seasons.

*

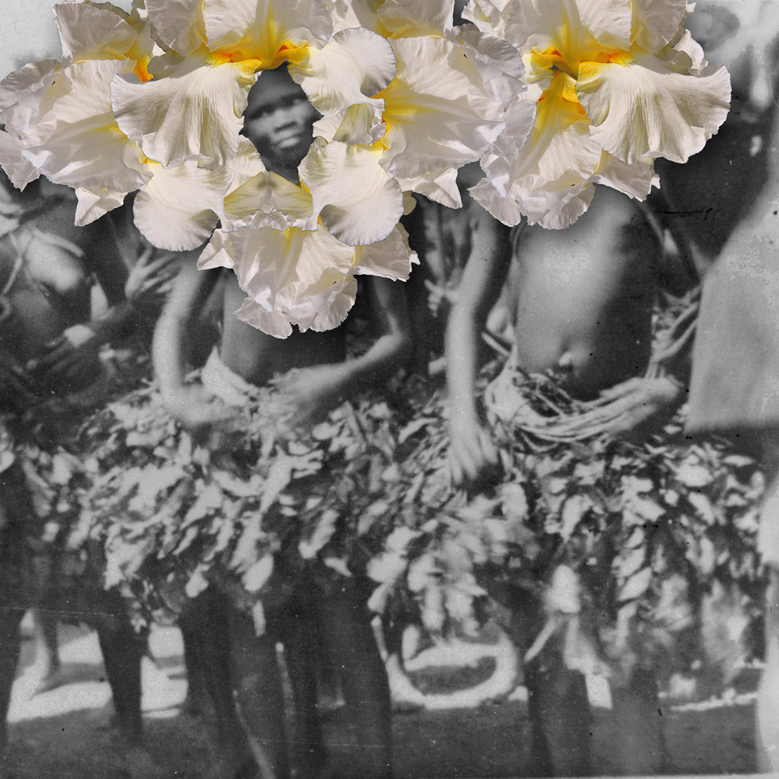

In her Flowers Series, Gabonese artist Owanto reminds us of how the colonial lens could sometimes go as far as invading vulnerable moments during a female initiate ceremony. One imagines a stranger looking on, into an age-old ritual and capturing private moments created to define womanhood. One wonders if that gaze leaves its own kind of mark, a scar that deeply diminishes the girls’ dignity.

Owanto uses small found photographs and enlarges them to two meters high. In some of the most shocking pieces, the camera has shot the girls, legs splayed open, to reveal the part that has been circumcised. Owanto first came across the small celluloid images amongst her late father’s belongings. She was deeply disturbed by them and put the stack in a place where they could be forgotten. However, they had an unyielding hold on her which led her to explore the issues around FGM/C and thus began the Flowers Series. For whom were these photographs taken for? Once washed in a darkroom, who was the intended viewer and why was this necessary? Other photographs from this series let us know that the people who were documented in her work were part of a community whose ceremonies were captured in a place formerly known as Afrique Équatoriale Française, most likely in the 1940s.

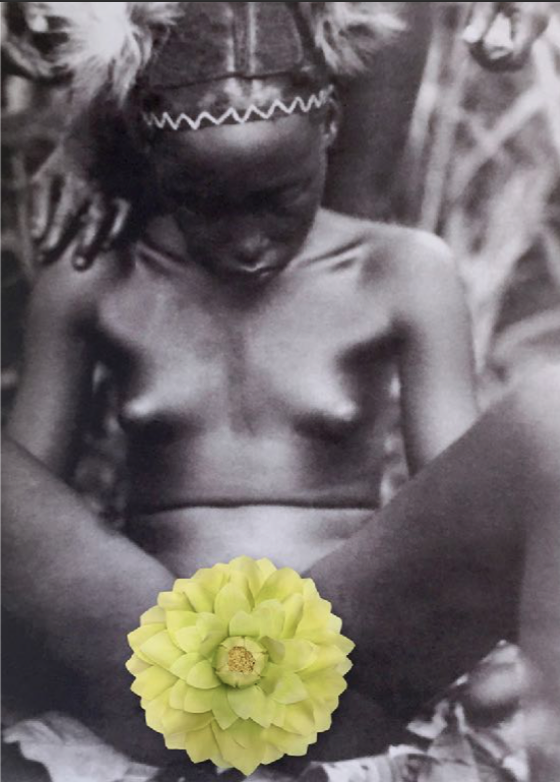

Flowers III, 2015.

When looking at the Flowers Series, at first, it may seem like further violation to enlarge these photographs and place them in a museum. Indeed, it may on the surface seem like a profound othering or yet another exploitation of the black female form. One wonders if this enlargement reinforces xenophobic or Eurocentric undertones that can still be heard in many places today. Whispers still describing a dark or magical Africa laden with backward practices. Does this enforce a voyeuristic gaze on unknown subjects whose image bears no real provenance? Or does this create a form of empathy?

Perhaps, how the image is manipulated, and by whom it is presented reframes the matters at hand. Here the photograph is repurposed to communicate a new narrative where the colonial gaze is appropriated to recant the story from a different angle. There is a reclamation. The space which had been previously captured by an outsider is repossessed by one positioned from post-colonial space. The one who now wields authority is herself a woman with African ancestry. Perhaps this is enough of an enabler that lets her provoke further questions regarding the politics of the colored body. Blown up, the photograph becomes a dominant object that boldly displays a shift in authorship.

*

Owanto, uses these old photographs to highlight the complexities of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C) which is still prevalent today. Owanto first came across the small celluloid images that she uses in her work amongst her late father’s belongings. She was deeply disturbed by them and put the stack in a place where they could be forgotten. However, they had an unyielding hold on her which prompted her Flowers Series. She uses the contentious depiction of an age old ceremony in order to bring discussion around what is largely deemed a harmful custom. However, there is a risk in that she too, like the colonial voyeur, could be accused of speaking on behalf of another and portraying a singular story. She may not be from the communities for whom this type of initiation reaffirms ideas of identity and belonging. After all, circumcision and initiation have long been seen as positive markers of maturity. Who then has the right to stigmatize a practice that is not one’s own?

Flowers II, La Jeune Fille à la Fleur, 2015, courtesy the artist.

Yet at the same time, there can be a danger in silence. FGM/C is today widely seen as a violation of human rights, a practice which is in many ways entrenched in misogyny. Female circumcision has no proven health benefits. This procedure is often carried out on children who cannot consent. Over 200 million women and girls are affected by FGM/C today. (2) This wounding has long taken place in specific parts of the Middle East, Africa and Asia, as well as in small communities in North America and Europe. The urgency in this issue is what compels Owanto to bring this to light.

*

Yet, to name a body of work that speaks to uncomfortable histories and ugly present day truths, Flowers Series might seem ironic. Even the titles of some of the individual works, Flowers IV or La Jeune Fille À La Fleur do not out rightly convey the controversy of female circumcision. Rather they convey light and innocence that has connotations of growth and beauty. However, this is how the artist has chosen to bring healing to the subjects in the photographs and the matters that they now represent. In each work, Owanto inserts porcelain flowers over the cutting. In the pieces where the wounding is not displayed, flowers are set over sullen expressions. These floral protrusions are synonymously masks, crowns and shields. They mask several violations, violations that are as a result of both the cutting and the camera. The flowers protect the girls from onlookers. Perhaps having more eyes prodding at this pain would be problematic, therefore a large hole is cut out of the photograph and a void is replaced by a flower. Now the flower conceals the injury. The artist has also protected viewers from trauma. If FGM/C is the epitome of discrimination against women, then the flowers make processing the suffering a degree less confounding. The handmade petals are delicate and intricate yet hard and secure. No matter the edition, no one flower is the same, each one is distinctively designed. By adding this floral intervention, Owanto bestows on all individuals who have undergone the cutting a medallion of recompense.

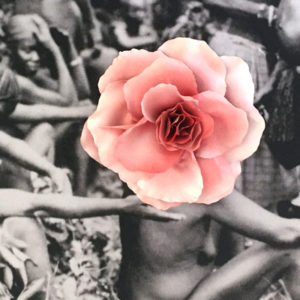

Flowers, 2015, courtesy the artist.

Yet to some, the term deflowering maybe laden with negative prejudiced innuendos. A deflowered girl is someone who has suffered a loss or has had part of her plucked away forever. Deflowering has connotations of labels carried only by women. However, just as Owanto appropriates the colonial photograph, she challenges classifications that are based on anatomical insinuations. In some ways, she reinstates all women’s identity by naming the work Flowers Series. For the woman, there is now an affirmation allowing her to thrive regardless of being circumcised or uncircumcised, virgin and non-virgin, assaulted or unharmed.