With the gaining of independence of several African countries, Africans in photographs began to have more and more of a say in how they were photographed. This agency, this power to dictate how they wished to be seen became entrenched in the practices of African photographers after the colonial era.

What does any of it have to do with painting?

Joseph Omoh Ndukwu on personhood in the paintings of contemporary Nigerian artists.

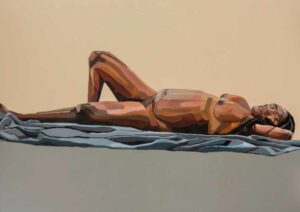

Tonia Nneji Far from Here, 2020

Personhood in the Paintings of Contemporary Nigerian Artists

In old family portraits, there is a certain gravitas. A certain awareness of the heft of the moment, the moment of the photograph. Family members sit with dignity, their comportement carefully attended, their gaze directed at the camera with admirable singularity. These portraits, of Nigerian families—at least the several family photos I have in mind as I write—were usually taken between the late years of colonialism and early post independence.

The camera was recognized for what it is, a maker of images in both the literal and metaphorical sense. The camera made images, the physical picture, and in a sense made the image of the one or the thing photographed. It determined how he would be seen for as long as that photo is looked at. The sitters in family portraits recognized this. It was no matter to be trifled with, this business of having your photograph taken, or to put it in the right context, to have your image made.

As Barthes relates in Camera Lucida, photography is a deep contract and relationship between the photographer, the subject, and the image. With the gaining of independence of several African countries, Africans in photographs began to have more and more of a say in how they were photographed. This agency, this power to dictate how they wished to be seen became entrenched in the practices of African photographers after the colonial era. Photographers like Seydou Keïta, Malick Sidibé, J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, James Barnor, and Oumar Ly realized there was something wrong, something denigrating, about the ethnographic photographs taken of Africans by White Europeans. So, they made it a focal point of their practice to privilege the agency of the subject. In their photos, the subjects clearly evinced the air of people who were active participants in the making of their own image.

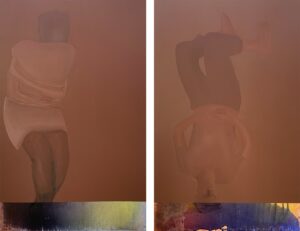

Joy Labinjo, Terra Firma, 2022, courtesy Tiwani Contemporary

This is all related to photography. What does any of it have to do with painting? For all their differences, there is the obvious idiom connecting them: the making of images, the creation of a visual experience. There is also—and I think this is more important—the matter of reflexivity: the complex negotiation of looking at oneself and projecting the result of this looking at the world.

The artist, in making a portrait, sometimes works from a model, sometimes from a photograph. He is creating a picture, but unlike a photographer, he is not simply selecting the most pertinent frame out of countless possible others from the stream of time. Rather, the painter, even when he is working from a model or photograph, is creating the frame; he is deciding, entirely, the look of the moment and the subject. The ability of photography to make an image as it captures a moment throws into sharp relief a similar, if not greater, power shared with painting.

In an essay on Derek Walcott, Jamaican poet Kei Miller recounts an event in which the writer Earl Lovelace says to him, with genuine concern: ‘What do you guys have? You know – we had Independence, Nationalism, Black Power. We had anthems to write, histories to record. You see what I mean? But your generation… I’m not sure I know what it is you have? I’m not sure what you stand for?’ Kei Miller, later in the essay, trying to answer the question, writes: ‘I simply repeat the old Rastafari saying – the full of the story has never been told. At other times I try for a metaphor. I tell him that his generation of writers, they had created a house. And always with a house there is an inside and an outside. We are interested in the outside—in the people […] left out…. There was always an outside—a dark and unwritten place.’

This, I think, is what contemporary Nigerian artists are doing in their paintings. They are reaching for the dark, unwritten (or in this case “unpainted“) place. When I use the word “unpainted,“ it is not to be understood in the absolute sense. For nothing, really, has been unpainted. But I am referring to how increasingly more attention is given to the intimate, the personal, and the individual in the work of these artists. While they almost always engage with society, this engagement is done more from an inward place, from a place that privileges the individual.

Personhood runs as a theme through several of the paintings of these Nigerian artists. In Joy Labinjo’s exhibition Full Ground at Tiwani Contemporary, Lagos (until 7 May, 2022), for example, we see a body presented as a political force, as a counterweight to objectification. The paintings are self-portraits of the artist in the nude. It is interesting to see what the artist does here. She puts the body as a counter to what it has been named. In a seemingly counterintuitive fashion, she challenges the gaze that objectifies. In her hands, nudity, to borrow from John Berger, becomes a kind of dress. In the paintings, the artist strikes different poses: in some, she stands erect; in others, she is recumbent; in yet others, she is on the move. All of this forces the viewer to see the subject, first, as a full human being, and then, to contend with that.

Wilson Imini, Girl with the Shasta Daisy, 2021

In his studio in Dei-dei, Abuja, Wilson Imini, a young dedicated artist, told me, as we stood looking at one of his paintings, that he wanted to paint the side of the subject that people had not seen. The painting is titled Girl with the Shasta Daisy (2021). In the painting a girl in a beige dress and green checked pinafore stands against a blue background. She looks out with a sad yet intense gaze. There is a daisy in her hair, with a row of them behind her. She is beautiful, but not in the conventional sense popularized in media and advertisement. ‘She is the kind of person you’d say is ugly,’ Imini said. ‘But I wanted to show her beauty, so I painted her a bit differently, although she would still recognize herself when she looks at the painting.’

The portraits in his œuvre, he related to me, are made as gifts to the people he depicts, some of whom include Kanye West, Barack Obama, and Malcom X. The portraits celebrate their accomplishments and strength of character. In a few of the paintings, he portrays his subjects with halos, a symbol of saintliness, on their heads. Some of them are young people with dreadlocks, people who may have been called miscreants.

This aesthetic is important now more than ever when the individual has been devalued by the oppressive powers that govern society. Against the backdrop of a world that incited the #EndSARS protests of 2020, the Black Lives Matter movement in the USA, and many other demonstrations against the increase of state-sanctioned violence against civilians across the globe, against this backdrop, it becomes urgent to re-examine how we look at the ‘person’.

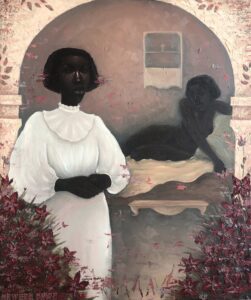

Odeyemi Oluwaseun’s Home Boy (2022)

The field for exploration with regard to this is large. It cuts across resistance, mourning, identity, beauty, intimacy, agency, introspection, and collective progress. A look at Odeyemi Oluwaseun’s Home Boy (2022), currently showing in the group show Serenity at Mitochondria Gallery, Texas instills in the viewer the conviction that an exploration of personhood in painting is elastic enough to hold all of these concerns.

Sometime in early January 2022, while viewing the exhibition It’s a wRAP at Rele Gallery, Onikan, Lagos, I was taken by the paintings of Michael Igwe. His works were hanging on the ground-floor, sharing the space with several other paintings, for it was a group show, but they commanded their own quiet. His Sleeping Anguished Boy (2021) now that I look at it again impresses me with its self-possession and vulnerability, its dreamlike atmosphere and mystery. A figure lies in a foetal pose to the left of the canvas. Both the figure and the canvas are painted a dusty mauve, except for a small strip of transparent indigo at the base of the painting, covering the feet. It is a most affecting evocation of quiet and vulnerability.

Left: Michael Igwe, Sleeping Anguished Boy, 2021

Looking at this painting brings to mind the thoughts of Kevin E. Quashie, author of the Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture. He speaks and writes of a balance between resistance and intimacy, a balance between an express political message and a recognition of inwardness in discourses surrounding Blackness. There must be room for quiet in our understanding of Black people. It is this balance, this wholesome view, that enables us to see Black people at their most beautiful.

Chinma Nnoli, A Poetry of Discarded Feelings things ii, 2022

The strength of this current—if not a movement—in contemporary Nigerian art is its reflexivity. It is both outward and inward-looking. It is a widening gyre and artists too many to mention: Tonia Nneji, Chidinma Nnoli, Wilson Imini, Joy Labinjo, Michael Igwe, Chinaza Agbor, Odeyemi Oluwaseun, and others are looking to their study of the ‘person’ to get at the root of matters pertaining to identity, self-reclamation, individual autonomy, human dignity, power and resistance, concerns that have always remained with us all through the ages. Their approach to them is worthy of our attention.