The historical memory underpinning ‘The Matter of Memory’ is that of British colonialism in Kenya. The story of the Mau Mau insurrection in 1952, its brutal suppression, and the subsequent state of emergency which lasted until 1962, is a site of complex and contested narratives beyond the scope of this text. But the Mau Mau is an inescapable, traumatic presence in the very fabric of Boswell’s installation.

Yvette Greslé on the installation ‘The Matter of Memory’ by Phoebe Boswell

The Matter of Memory, 2013-2014, installation.

Phoebe Boswell: The Matter of Memory

Phoebe Boswell. ‘The Matter of Memory’, 2013-14. Installation view at Carroll/Fletcher [detail]. Courtesy the artist and Carroll/Fletcher.

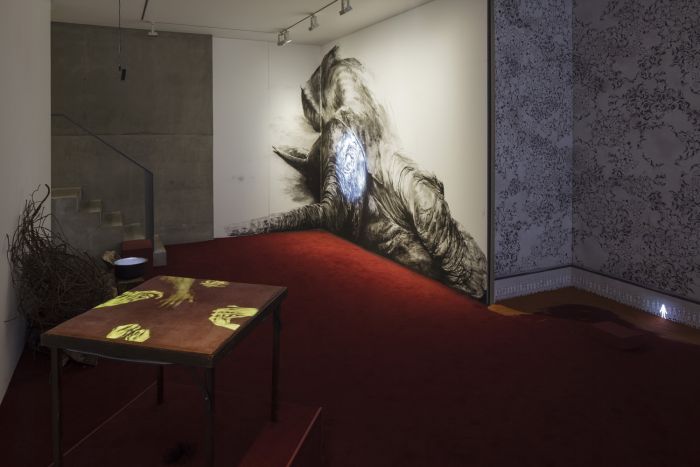

Phoebe Boswell. ‘The Matter of Memory’, 2013-14. Installation view at Carroll/Fletcher [detail]. Courtesy the artist and Carroll/Fletcher.

I settle into an armchair and am surprised by voices audible from a mechanism buried in the fabric. I hear the voice of the artist, Phoebe Boswell, but also simultaneously, the voice of another. I discover that the chair on the right hand side (as I face the screen) transmits the voice of Boswell’s mother; and the other that of her father. Each parent narrates their memories of life in Kenya, where both were born, raised and married. As they narrate, their child (the artist) repeats their words. This device of multiple, simultaneous narration, does not obscure the speech of each. When the father pauses, the daughter pauses, when the mother sings, the daughter sings. This is a work of memory, a deliberate, staged act of remembering, but it is also a work of familial intimacy. The daughter appears to cherish the memories of the parents, repeating them so as not to forget. This gesture is poignant, it resists erasure and forgetting, and anticipates the inevitability of loss.

*

The armchairs, with their audio, are titled ‘When I Hear My Own Voice, I Can Hear Kenya’ (2013/14). These sound-objects are an important component in what is an immense spatial installation occupying the whole of the basement level of the Carroll/Fletcher Gallery. Titled ‘The Matter of Memory’ the work encompasses sound, looped projections, animations, objects, and drawings. It embodies the existence of multiple, simultaneous narratives functioning strategically to oppose assumptions about the world in which we live. Deeply sedimented racial prejudices that still hold the world in their thrall are potently countered and resisted. Boswell’s ‘The Matter of Memory’ draws attention to the continued critical significance of human subjectivity, and memory-work, as a counterpoint to the tyranny of singular, overarching narratives.

*

As I listen to the voices of artist and parents many other sounds are audible and drive the experience of the work as a whole. I listen to the repetitive gasping of a looping animation of a miniature of a girl who dives in and out of a pool of milk. The sound is unsettling, and detached from the idiosyncratic figure to which it refers, it produces sensations of anxiety, claustrophobia and suffocation. Another animation (so small and innocuous it might remain invisible) is projected onto the teapot laid amongst the tea things on an antique table. The printed, white crockery is pretty: on the teapot is a tree, delicately drawn, its branches reach up onto its lid. A man, grasping a red whip, beats a figure, its form obscured and huddled against the tree trunk. The animation is visible not from the chair inhabited by the mother’s voice but from that of the artist’s father. At one point, he speaks of a childhood memory: his witnessing of the brutal beating of an old Kikuyu man, stripped, wrapped in a blanket, and shackled to a tree. The animations which are ephemeral, and often hidden in places we may not necessarily think to look, enters into a poetic dialogue with the fragile matter of memory. Sometimes we imagine that it is possible to bury what is too painful to think of. Traumatic memory is often described in terms of insistent repetition and return, of the surfacing of memories we would rather suppress: in Boswell’s work it is registered in the looping of sound and image. Sounds such as the repetitive gasping of the swimming animation; and the insistent drip-drip-drip of water on a card table (onto which disembodied, ghostly hands are projected) haunt the space of this work and inflect how it is I look.

Phoebe Boswell. ‘The Matter of Memory’, 2013-14. Installation view at Carroll/Fletcher [detail]. Courtesy the artist and Carroll/Fletcher.

Phoebe Boswell. ‘The Matter of Memory’, 2013-14. Installation view at Carroll/Fletcher [detail]. Courtesy the artist and Carroll/Fletcher.

Narratives of multiple-heritage and displacement are ones that many twenty-first century subjects, emerging out of historical conditions of travel and migration, can relate to. Boswell’s British-born, Kenyan father, is a fourth generation Kenyan settler and her mother is Kikuyu Kenyan. Visual significations of colonial settler life into which the artist’s father was born, and the Kikuyu Kenyan heritage of her mother is present throughout the installation. The story of this family is one wound up in migration: Boswell who moved to London in 2000, was born in Kenya but grew up in the Middle-East. She now lives and works in London having studied painting at the Slade School of Art and 2D Character Animation at Central St Martins. ‘The Matter of Memory’ invites us into the most intimate spaces of Boswell’s family history. It speaks about the presence of love despite the borders dreamed up by the historical obsession with racial difference. But this work is certainly no idealistic account of the transcendent capacities of love in conditions of trauma and social and political violence. Kenya inhabits the memories and the emotional life of mother, father and daughter who negotiate belonging, displacement, and ideas of ‘Home’.

*

The historical memory underpinning ‘The Matter of Memory’ is that of British colonialism in Kenya. The story of the Mau Mau insurrection in 1952, its brutal suppression, and the subsequent state of emergency which lasted until 1962, is a site of complex and contested narratives beyond the scope of this text. But the Mau Mau is an inescapable, traumatic presence in the very fabric of Boswell’s installation. The Mau Mau is present in the images and sounds that recall the significance of Kikuyu Kenyan relationships to land; and the related violence of British colonial rule. Boswell’s projection ‘Land’ (which I viewed from the armchairs) is a work of monumental scale. It incorporates found photographs collaged onto hand-drawings produced on a computer; footage filmed by the artist, and animation. The landscapes that emerge in the viewing of ‘Land’ inhabit the space of an imagined colonial living room with its upholstered armchairs and table laid for tea. The view from the armchairs invoke the power relations embedded in vision, the surveying of land possessed from the colonial verandah. Figures cut from photographs signifying British colonial power – armed, uniformed soldiers – appear and disappear amongst densely massed, hand-drawn human subjects. Lightning and thunder sound ominously in the exhibition space as these dense graphite figures darken: eyes, animated by the artist, flicker disconcertingly as they open and shut. The figures fade and are replaced with a photograph of Kikuyu people forced, by the colonial administration, to live in apartheid-style reserves cordoned off by wire fencing and rigidly policed. Boswell says of a young girl she filmed and then digitally placed in a hand-drawn field (in ‘Land’): ‘that is a memory that my mom told of running through a wheat field’. A yearning to return to Kenya is unmistakable in the narratives of mother and father, situated in the temporal collapse of past and present (and a future still only imagined). ‘Land’ closes with the figure of an aged woman who appears and disappears from multiple points within a landscape of trees (a church building in the background). She builds a fire, echoed in an animation within the exhibition space itself, and suggested in the piles of wood incongruous on the thick red carpeted floor. Fire provides nurturing warmth and sustenance but it can also be dangerous and all-consuming. ‘Land’ closes with this figure as she looks back at us, her expression is one of an unbearable anguish we can see but cannot hear.

There is nothing more disruptive to flattened out political-historical narratives then the voices of individual human subjects whose choices and lives embody a critique of the various kinds of authoritarianism and compromised citizenships that continue into the present-day. Histories of colonialism were violent in the sense of brute force and legislation that enforced colonial power and the secondary status of colonised subjects. But they were also arguably violent in the sense of an insidious and controlling presence occupying the private and intimate sphere of the settler home. This presence was not necessarily always tangible or visible (although this was contingent on who looked and how).

*

The intimate sphere of sexual life, desire, love, marriage and the birth of children (across pre-determined racial divides) was tightly policed within colonial social structures. Mixed-race subjects threatened to render defunct the power relations and myths founded on difference, separation, and deeply cherished hierarchies. Boswell’s wallpaper print ‘Ciana ni Ciakwa (The Children are Mine)’ depicts dense groupings of human subjects amongst molecular structures. Of the construction of this extraordinarily detailed work Boswell says: ‘I drew all the figures by hand using graphite on paper. I then scanned all the drawing into the computer [….] Both my parents talk about people as the most important thing. My mother emphasizes the links between people, and I wanted to have these connecting figures. My dad talks a lot about DNA and genes and genetics and how race has absolutely nothing to do with anything.’

Phoebe Boswell. ‘The Matter of Memory’, 2013-14. Installation view at Carroll/Fletcher [detail]. Courtesy the artist and Carroll/Fletcher.

Phoebe Boswell. ‘The Matter of Memory’, 2013-14. Installation view at Carroll/Fletcher [detail]. Courtesy the artist and Carroll/Fletcher.

‘The Matter of Memory’ obscures many borders: lines between interior and exterior space are obscured, and domestic space is brought into a relationship with the natural world. Piles of chopped wood ready for the building of fires, with which to cook, sit incongruously on the carpeting; and fine, ochre colored dust lines the sides of the room. Dust suggests a relationship to place but also mortality and the ephemeral nature of memory. The title of the exhibition is taken from the novel Dust by Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor. Boswell also obfuscates borders between mediums. Photographic documents, animations and drawings share spaces and surfaces. Animations are projected onto substances such as milk. Drawings of landscapes are animated by shifting graphite clouds and trees that propagate and grow in front of our eyes. Flies dance around the eyes of a slain charcoal and carbon elephant. Birdlife appears in sound and image: Marabou Storks embellish tea cups and are the subjects of framed drawings. Boswell speaks of her own childhood memories of birds in Kenya. Sound, sourced from various places, and heard in the space of the gallery, collapse place and time: ‘there is audio of Nairobi Cathedral. I wanted a muffled sound. I didn’t want it to be incredibly jubilant. I wanted it to be difficult to listen to but also reminiscent of going to church. Both my parents talk about religion very differently’.

As I inhabit the world of Boswell’s work, I consider one of Griselda Pollock’s opening questions to her book After-affects/After-images: ‘can aesthetic practices, the creation of after-images, bring about transformation – this does not imply cure or resolution – of the traces, the after-affects of trauma, personal or historical, inhabiting the world that artists also process as participants in and sensors for our life-worlds and troubled histories?’ Those who were once colonial subjects are still living today, and the residues of their memories will live on in those of their descendants. In the field of scholarship, memory is a vast and complex subject. The vocabulary of memory ranges from nostalgia to trauma. Boswell’s ‘The Matter of Memory’ has significance to Kenya, and its specific history. But its mobilization of multiple, multivalent images, sounds and objects (simultaneously experienced) speaks, more broadly, to the question of how art objects enter history. Boswell’s work pushes me to think about what might be drawn from the embodied experience of affect, memory and subjectivity in art (conceived of here as Pollock’s after-image). What happens as affect, memory and subjectivity converge with the politics and history of colonialism (and its aftermath)?

References:

Extracts of the words of the artist, Phoebe Boswell, are drawn from an interview conducted at Carroll/Fletcher, 6 March 2014.

Pollock, G. After-affects/After-images: Trauma and aesthetic transformation in the virtual feminist museum, Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2013 (from the opening of the Preface).

Some of the ideas that appear in this text are drawn from my PhD research, in progress, on South African video art, history and memory.