This is the 5th article in a series of articles on the friendship between ‘two’ African American artists, a “friendship beyond understanding”. In every article The Harlem Renaissance is the context of the story. This article is about the friendship between the poet Langston Hughes and the opera singer Gilbert Price.

Rob Perrée tries to answer the questions the friendship evokes.

First published September 2020

Langston Hughes (photographer unknown)

PORTRAIT OF A FRIENDSHIP 5: LANGSTON HUGHES AND GILBERT PRICE

In the late 1980s, at a party hosted by a friend, I met the British artist Isaac Julien in New York. At the time he was not well known. Despite this, many guests gathered as groupies around the sofa he had settled on with his then-boyfriend. He said he was allowed to work in New York for a year on his next project. A generous artist in residence program made that possible. He stayed temporarily in an apartment in the West Village. On Christopher Street, at the time the mecca of gay New York. A location I dreamed of when wandering through The Village. Despite the urgent questions from his fans, he did not want to say anything about the content and form of that project. It would have to do with Harlem and it would be controversial.

Isaac Julien | Pas de Deux 2 (Looking for Langston Vintage Series), 1989/2016, courtesy Ron Mandos Gallery, Amsterdam

Looking for Langston was released in 1989. A work that moves on the boundary of a revealing documentary and a poetic feature film. Shot in black and white. The title refers to the Harlem Renaissance poet and writer Langston Hughes. Julien places him in the decadent world of the Harlem speakeasies of the 1920s, which can be compared to the London nightclubs of the 1980s. Most notably in terms of the ambiguous sexual subtexts of the period. Looking for Langston is also a quest for the poet’s homosexual identity. Julien completes his quest in a convincing way: Hughes is gay, according to Julien.

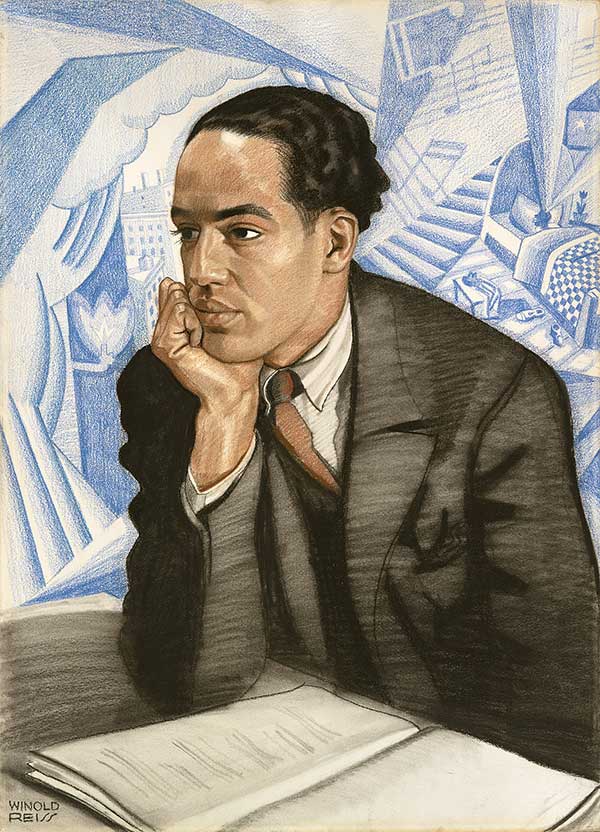

Langston Hughes (1902–1967) by Winold Reiss (1886–1953) National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of W. Tjark Reiss, in memory of his father, Winold Reiss

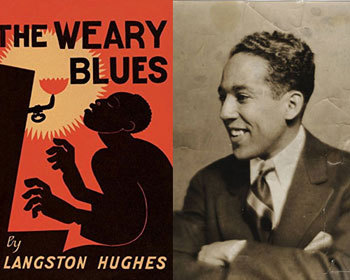

On Sunday, January 31, 1926, Langston Hughes presents his first collection of poetry, The Weary Blues, at the Shipwreck Inn, 107 Claremont Avenue in Harlem, a then well-known but now disappeared catering establishment near Columbia University. According to his biographer Arnold Rampersad (1), it attracts nearly two hundred visitors. That may seem like a lot for a young black poet, but Hughes has already published a number of poems in, among others, “Crisis”, the magazine of the activist historian W.E.B. Du Bois, author of the collection of essays “The Souls of Black Folk” (1903); in “Opportunity”, “a Journal of Negro Life”; in the socialist “Messenger” and in “Vanity Fair”. In addition, he has received prizes for his poems from the first two magazines. His name is established in Harlem. He has a large group of loyal readers. After the presentation he has to sign many copies and provide them with an assignment. The first printing of 1200 copies is sold out in a short time.

The Weary Blues, cover design Miguel Covarrubias

The Weary Blues is published by Alfred A. Knopf, a white New York publisher. This makes Hughes uncomfortable, but he realizes that he has little choice when it comes to bringing his work to the people. He also feels uncomfortable because his poems focus on the black working class, while he will never reach that audience, even if he opts for a free, readable form and a rhythm that is recognizable to blues and jazz fans. Colleague County Cullen likes to profile himself as a poet within the Western, perhaps even English tradition, Hughes wants to be a black poet who makes work that connects with black culture. In the essay The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain, which he also published in 1926, he makes a clear statement:

Most of my own poems are racial in theme and treatment, derived from the life I know. In many of them I try to grasp and hold some of the meanings and rhythms of jazz. I am as sincere as I know how to be in these poems and yet after every reading I answer questions like these from my own people: Do you think Negroes should always write about Negroes? I wish you wouldn’t read some of your poems to white folks. How do you find anything interesting in a place like a cabaret? Why do you write about black people? You aren’t black. What makes you do so many jazz poems? But jazz to me is one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America; the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul–the tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a white world, a world of subway trains, and work, work, work; the tom-tom of joy and laughter, and pain swallowed in a smile.

Cover I Wonder as I Wander, autobiography of Hughes

Looking for Langston may take the view that Langston Hughes is gay, in fact Julien is interpreting an alleged reality. Beautiful, original, but not based on facts (that is not necessary if you choose a mixture of fiction and non-fiction as a genre). The poet himself hides his private life. He never speaks out about it. His poems are personal but never intimate. He does defend himself repeatedly against accusations that he is a communist, he does not defend himself as far as I know when writers and other people speculate about his sexuality. Arnold Rampersad says about this in the introduction to the second part of Hughes’ autobiography, I Wonder as I Wander:

“…….his private life is, by and large, closed to the reader. One learns of a few flirtations and involvements in Haiti and the Sovjet Union, in Cleveland and in Spain. But amusement dispels romance, and we are given few clues as to why Hughes never married or never publicly associated himself with a lover.”

*

In January 1964, a musical entitled Jerico-JimCrow is presented in a church in New York’s West Village. The New York Times calls it “…… an unabashedly sentimental and tuneful history of the Negro struggle up from slavery”. Langston Hughes is the author, Alvin Ailey the director. One of the protagonists is the young baritone Gilbert Price.

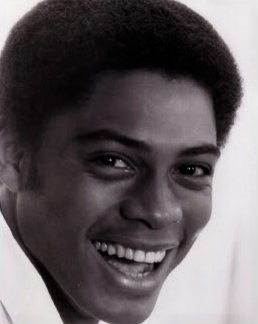

Gilbert Price (photographer unknown)

Gilbert Price performs “Old Man River” in this rare TV appearance from 1967.

Price (1942) was born and raised in New York. At Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn, his singing talent is recognized and rewarded: together with Barbra Streisand, he becomes the lead singer of the school choir. In the early sixties he tours with, among others, Harry Belafonte. Hughes asks him for his musical and acts as the singer’s protégé. Not only is the press impressed by the handsome appearance with “the best Negro voice I have ever heard,” the “pioneer historian for LGBTQ communities” Stephen A. Maglott claims on his Ubuntu website that Hughes falls for Price, like a block. During the run of the musical, they are inseparable and the poems he writes at the time are testament to it. Says Maglott. Arnold Rampersad, Hughes’ biographer, tells a similar story, a little more ‘dressed up’. Gilbert Price contradicts the suggestion that he had a romantic relationship with Hughes. “There was nothing more to it than a deep friendship, and nothing less.” And: “I was grateful and blessed to be with him. I got joy from him and a great deal of understanding, and I know that he got joy from me. I saw his loneliness, but he never let it come between us. ”

*

The second part of the autobiography of the Harlem Renaissance poet ends in 1955, nine years before Price crossed his path. Whatever they write or think about him, and whoever those “they” are, the supposed “dark” side of his personality remains unproven.

Hughes dies in 1967. In October of that year he is commemorated by the COC, the Dutch interest group for lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgender people, in Hotel Krasnapolsky in Amsterdam. Well, yes. Price dies in 1991, age 48.