“Sirmans has created a carefully composed biennial. The selected artists ‘serve’ his concept, their work is linked to the ‘character’ of the environment in which they are exhibited, without becoming exclusively local or national. In the themes they are talking about – Sirmans uses the word ‘conversation’ a lot – they often meet each other, not in the least because of the thoughtful installment of Sirmans.”

Rob Perrée on Prospect 3 in New Orleans.

Herbert Singleton, Angola, 1990’s.

‘PROSPECT 3’

THE ART OF COMMITMENT

Franklin Sirmans, the curator of the ‘‘Prospect 3’’ Biennial in New Orleans, is a man with ideals, with dreams, with a mission and with a vision. For him ‘Prospect 3’ has to be an investment in the search to find the self, and in the necessity of ‘ the Other ‘ as part of that quest.” He considers questions like; Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?’ For him these questions are of great importance.

This is why he includes the piece ‘Under the Pandanus’ (1891) of Paul Gauguin. The French artist was searching for the answers to these same questions.

This is why the work of the participating artists in this Biennial need to have a relationship to the environment in which the work is presented. The work has to create a conversation with the South, with New Orleans, with a community where a high crime rate go together with lively celebrations and celebratory rituals like Carnival and Mardi Grass. A place where music is essential. Where voodoo shops and gift shops are neighbors. A place where many cultures come together and where race is an issue. A place where a drama like Hurricane Katrina could disrupt the whole city.

Franklin Sirmans hopes and thinks that art can have a function in a world “where nationality, race and religion continue to divide rather than unite.” Call him naïve if you want (perhaps he is), but you also can call him personal and committed.

‘Prospect 3’ has 58 participating artists; 44 are artists of color, and 22 are African-American. The biennial shows work at 18 locations around the city. The off-biennial, P3+, is spread over 51 locations. Guest curator or artistic director Franklin Sirmans, is a curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) .

With so many participants and so many locations it is impossible to cover P3 completely.

I limit myself to a selection of my personal highlights.

TERRY ADKINS / WILLIAM CORDOVA

Adkins (1953-2014) was a sculptor and a saxophonist. For him there was no dividing line between fine art and music. “My quest has been to find a way to make music as physical as sculpture might be and sculpture as ethereal as music is.”

He often used found material – instruments, wood, cloth, junk, coat hangers etc. – and because of that his work seems familiar, but the way he used these items, or better, the way in which he modified and composed these items, gives his sculptures a high degree of abstraction. By using found material he linked his work to (black, African) history, without making black culture an overall theme of his work. His performances were homages to black heroes like King, Hendrix, Coltrane, and Bessie Smith. His work was also influenced by philosophy (by ‘The Souls of Black Folk’ of DuBois for instance) and spirituality.

In this installation – Ezekiel’s Wheel and Ezekiel Double Drums – all this elements come together.

The installation was commissioned in 2009, but Sirmans decided to include the work to let it come alive and, because Adkins died recently, to let the legacy of a great artist go on.

William Cordova (1971), presented at the same venue, made a documentary film to honor the artist (Adkins). Eight musicians – the Rebels Band – climb to the roof of an New Orleans building and, facing the statue of General Robert E. Lee – controversial Confederate / rebel leader in the US Civil War – they improvise a musical tribute to Adkins. Because the film is elementary, almost simple, the effect is all the more touching.

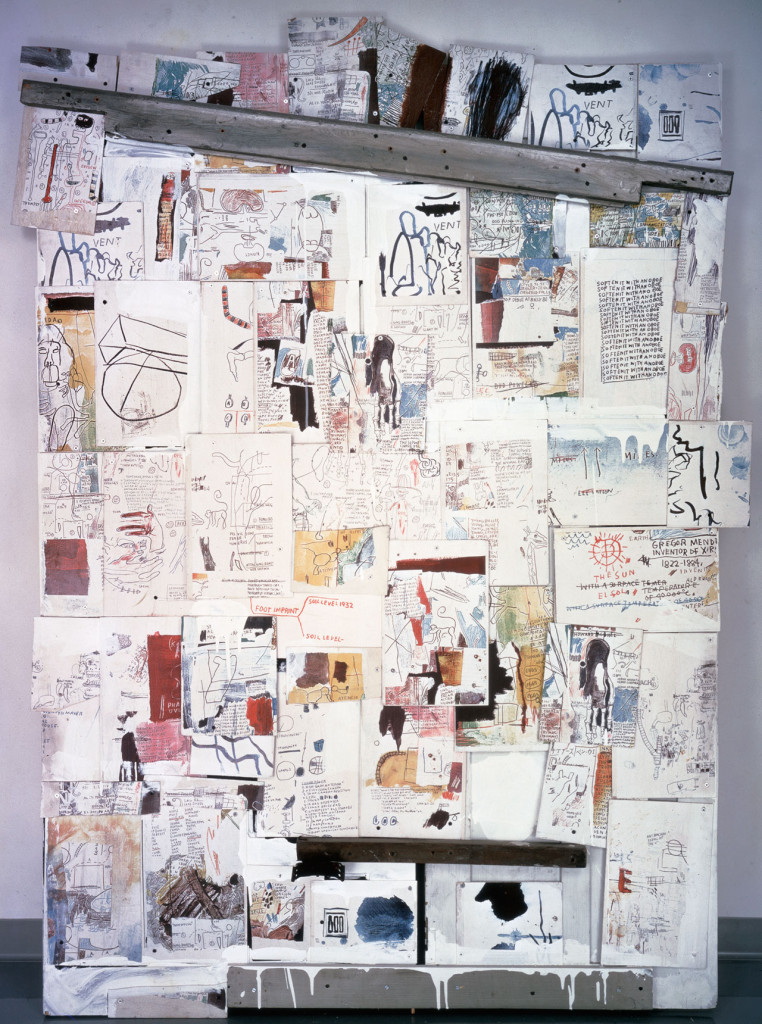

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT / HERBERT SINGLETON

Basquiat (1960-1988) visited New Orleans shortly before his death. His visit was not surprising. The Mississippi as a strong symbol of the South is present in several of his works. The music of the South is an even more prominent reference. Miles Davis and Louis Armstrong were his heroes. He was familiar with zydeco, southern blues music which originated from Cajun and Creole culture.

This small exhibition within the bigger context of ‘Prospect 3’ illustrates his relation with the south. Most of these works are not very well known. I don’t know why. Some of them – ‘Natchez’ (1985) for instance – is an apparently random and sloppy composition of little drawings, partly overlapping each other. They read like a diary fallen apart.

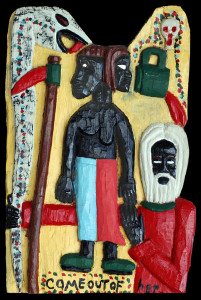

Herbert Singleton, Come Out of Her, 1980’s (Collection Gordon Bailey)

Herbert Singleton, Come Out of Her, 1980’s (Collection Gordon Bailey)

The room with Basquiats is neighboring the room with colorful sculptures and wood paintings of Herbert Singleton (1945-2007), an outsider artist from New Orleans. That presentation shows clearly that Basquiat’s imagery is influenced by self taught artists like Singleton. It also shows that not only in the paintings and drawings of Basquiat text and image can go together in a natural way.

ZARINA BHIMJI

A few years ago I saw the film ‘Out of Blue’ of Bhimji (1963, Uganda). It is a breathtaking registration of the destruction of an African village, or the suggestion of the destruction of that village. The combination of beautiful images and indefinable sounds of animals (in danger) created a strong feeling of threat. The absence of human beings has a comparable effect. What happened to them? Did they flee? Did they die?

“My work is not about the actual facts but about the echo they create, the marks, the gestures and the sound. This is what excites me.”

‘Jangbar’, the work presented in P3, explores the spaces of an abandoned factory building. Again, specific information is lacking. What kind of building? Why is it not in use anymore? What were they producing there? From outside information I know that it is a sisal factory near Mombasa, Kenya. The film itself leaves it open. On purpose of course. The mystery in this film is not threatening, ‘Jangbar’ is a poetic quest. It shows detailed, mesmerizing images of dusty corners, of sisal remnants hanging down, of the effect of light on these remnants. They make you curious, they draw you in. You can’t stop watching. It is almost a lesson in meditation.

Could the influence of colonialism be at the background of all her work?

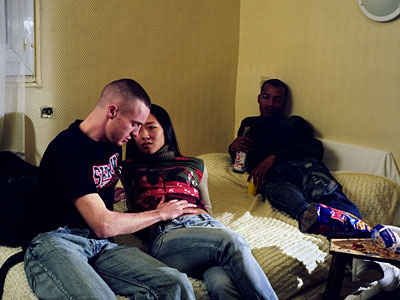

MOHAMED BOUROUISSA

Mohamed Bourouissa (1978) is an Algerian artist living in Paris. He shows a series of photos – shot in the Banlieues of the capital – of young people from different cultures hanging around on the streets, gathering, smoking, arguing, attempting to date. The photos don’t focus on technical beauty but on the manner in which young people communicate. It looks as if they are staged. In any case, they are narrative. The characters in the stories look all very serious. Especially the photos shot in the evening are often depressing and sad. As a viewer you tend to use the most pessimistic part of your fantasy to give the images a storyline.

The overall impression of the series does not match with the violent image the French media are trying to get convey. Bourouissa shows the boring, sometimes empty lives of young people in the suburbs of Paris. He shows a life without hope, without any perspective. Implicitly he ‘accuses’ the government of not paying attention to the reasons why these young people make trouble.

Because Bourouissa has built a close relationship with his ‘models’, some images are very intimate. This is an intimacy comparable to that seen in the early Nan Goldin or David Armstrong photos.

JEFFREY GIBSON

The work of Gibson (1972) can be confusing. On one hand he makes geometric wall sculptures, composed of colored surfaces. They remind me of the wall paintings of Donald Odita (one can be seen in the New Orleans Museum of Art). They are minimalistic and conceptual.

On the other hand he makes sculptures and objects in which he visualizes his Choctaw and Cherokee Indian background. ‘Watching Forever’ (2014) is made of found material: among others deer rawhide, glass and plastic beads, wool blanket, crystals, arrow heads and artificial sinew. It refers to Native American motives and symbols. It challenges the thin line between art and craft. It is the opposite of minimal.

Gibson seems to illustrate the complexity of American culture where traditions and new developments have to live with each other, where Non- Western art has to deal with Western ways of expressing, where culture and subculture must tolerate each other.

REMY JUNGERMAN

It is interesting to see how context can change perception. I know the work of Jungerman (1959, Suriname) from exhibitions in The Netherlands. There most visitors understand the colored grid works as a reference to the art movement De Stijl (1917) without much of a problem. The painted bottles on some of these works need more time to be understood. In New Orleans, where religion is a dominant factor and voodoo and its rituals are familiar to a lot of people, the perception of the work is the converse.

When Jungerman decided to move from Suriname to the Netherlands, his first works were installations on communication, or better, on the lack of it. After the death of his father and the experience of the Winti rituals that went with it, the elements of Surinamese culture returned in his work. At first with various recognizable objects, symbols and signs combined with Dutch equivalents, but gradually abstraction set in. His presentation in Prospect shows that development. The forms are geometric. Straight horizontal and vertical lines. Literal references have lost their literalness. Cubical forms appear. They are covered with fabrics that refer to the traditional fabrics used and designed by the Maroons, but they also recall art works out of Western traditions.

In his newest, small, two dimensional works – ‘FODU.Conjunction’ (2014) – the fabric is used as linen to paint on. He presents them as a wall installation. Abstract, with subtle references to the Dutch and the Surinamese culture.

GARY SIMMONS

Gary Simmons (1964) is known for his erasure paintings and drawings on blackboards or colored materials suggesting the blackboard concept. In the meantime he also made installations and sculptures. Boxing is a returning theme. In his recent presentation at Metropictures, his New York gallery, boxing is even the central theme of the show.

The work he made for Prospect does remind me of the box arena he exhibited in 1994 for the first time. The boxing ring is now a wooden platform with, at the end, a stacking of sound boxes. All made from rough, unpainted material. On the platform are stars painted. They refer to the star that Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry used as a recognizable logo for his dub studio in New Orleans. The platform can be used for life performances. The boxes really can do their job.

‘Recapturing memories of the black ark’ (title of a Perry record) is presented in a run down bank building in the Treme, a black neighborhood in New Orleans, where there is hardly any infrastructure for entertainment and culture. Simmons must have picked this part of town on purpose. Like boxing music is an important part of black culture.

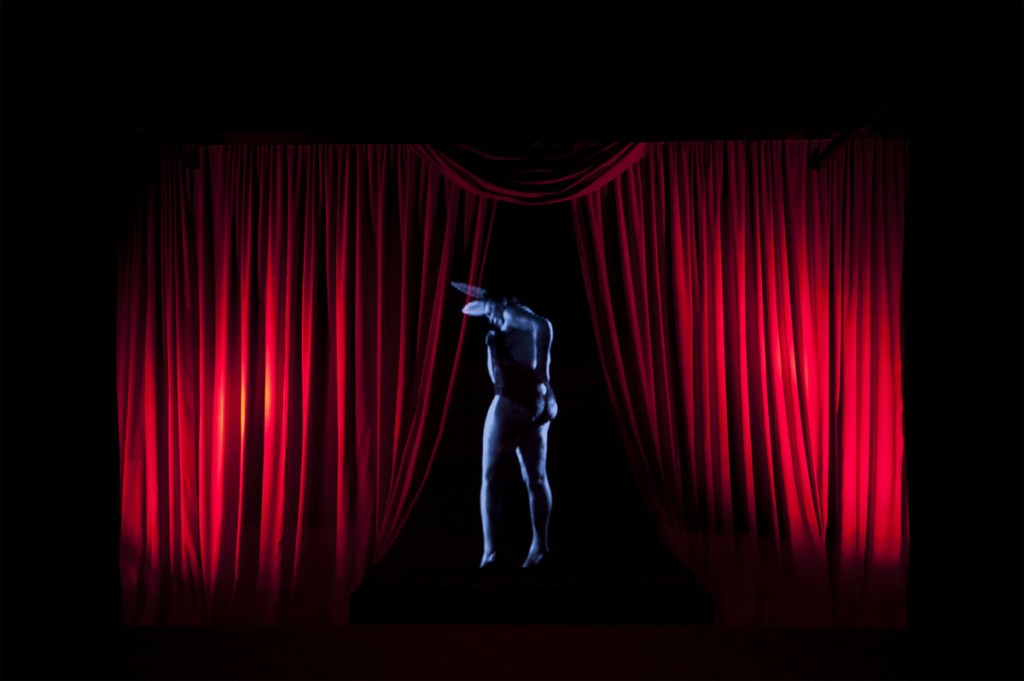

CARRIE MAE WEEMS

Weems (1953) shows photos from 2003 and the multimedia installation ‘Lincoln, Lonnie and Me – A Story in 5 Parts’ from 2012. The ‘Kitchen Table Series’ made her famous because of the intimate registration of her relationship with people close to her. In the ‘Louisiana Project’ she shows the relation of a women – herself, traditionally dressed, seen on the back – with houses and buildings that are symbolic for the black history of the South. They are stilled images which don’t need verbal or oral comment.

The installation suggests a podium with red curtains on which people from the past perform. Singers, dancers, musicians. They appear and disappear like ghosts. An illusion technique developed by John Pepper in the 19th century. Music transforms their appearance into a performance. A voice comments what the viewer sees, in a tongue-in-cheek kind of way. You imagine yourself in a variety theatre or a chic night club. You question your presence while looking at a past that has nothing or everything to do with you, depending on your perspective and origin. The voice of the artist seems to give you permission not to take it that heavily.

THOMAS JOSHUA COOPER

Cooper (1946) participates with a series of black and white photos called ‘Drowned Trees – A Mississippi River Tree Line’ (2010-2014). He travelled all along the Mississippi with his old (fashioned) Agfa camera to capture the identity of a river but also to confront himself with his own identity. His family once owned the land he is travelling through. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 forced them to leave.

It is rare to see photos with so many nuances in black and white. Light plays a big role. So much so, that it is not an exaggeration to compare his light and the effect of it with artists like Rembrandt or, more recent, with artists like James Turrell. Remarkable too is the suggested relationship between the trees and water. They seem to like each other, they communicate with each other, they embrace each other, and they seem to become one.

Because of the light, the overexposure of light, the images have a vagueness, a mistiness that gives them mystery. That triggers the imagination of the viewer. The absence of human beings underlines the importance of the river. It seems to be immune to human influence, and human power.

DIFFERENCE

Sirmans has created a carefully composed biennial. The selected artists ‘serve’ his concept, their work is linked to the ‘character’ of the environment in which they are exhibited, without becoming exclusively local or national. In the themes they are talking about – Sirmans uses the word ‘conversation’ a lot – they often meet each other, not in the least because of the thoughtful installment of Sirmans. He made surprising combinations. The themes often show commitment, sometimes they are even political.

Sirmans challenges the line between art and artifact, between high art and low art. He did not select the usual suspects. Although most of ‘his’ artists are well known, he did not go for the big, blockbuster names.

He is already criticized about the large amount of artists of color. A simple reaction could be: I never heard anybody complain about the large amount of white (male) artists in big exhibitions, but, since that reaction would be too easy, I will come up with a more objective one: Franklin Sirmons wanted ‘Prospect 3’ to fit in the context of the South, in the context of New Orleans, being part of the discourse that’s relevant in especially (but not exclusively) that part of the country. That starting point leads automatically to more artists of color.

Although it was not that obvious and it certainly did not disturb me, Sirmans had to select his venues carefully to make the biennial financially possible. The venues brought sometimes their own collection in (Dillard University) or they fitted ‘Prospect 3’ in their regular programming (New Orleans Museum of Modern Art, Ogden Museum of Southern Art). The trauma of the financial disaster of the first Prospect has not vanished yet…….

Sirmans also wants us to use art to re-evaluate our position and to seek an understanding of ourselves through the work of others. It is hard to say if that idea is realized. He managed to stimulate the conversation about art and the role of art within (a particular) society. That is already a lot.

As so many biennials, visiting all the venues is an almost impossible job, especially in a city where public transport is not perfect and cabs need time to get to places. No reason not to go to ‘Prospect 3’. It is growing into one of the most interesting and important international biennials. ‘

‘Prospect 3’ will be on until January 25.

www.prospectneworleans.org