Telting’s paintings are topical and relevant in their own right. I have discussed them from the point of view of Telting’s commitment as a Black artist, and I have linked his work to the concept of Black Aesthetics. I take it that, once his work is juxtaposed to works from the Stedelijk Museum’s permanent collection, new relations, perspectives and cross-pollinations come to the surface, and will continue to do so.

Dineke Blom on Quintus Jan Telting

Opus#1315, The Microspy Contraption

Quintus Jan Telting was a thinker.

On Telting’s paintings in School of Surinam: Painting from Paramaribo to Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, 2020-21

Late one afternoon, last October, I paid only a quick visit (thinking I’d be back the next week) to Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum to see School of Surinam: Painting from Paramaribo to Amsterdam. Pressed for time, I jotted down just three names in my notebook: “Baag – Quintus Jan Telting – Ron Flu: Prostitutes 1977”. As it turned out, the very next day the museum shut its doors due to Covid. So, six months later, I returned, this time for a proper look. The museum guard, Covid protocol in mind, pointed to where the exhibition begins, but I misunderstood him and started out not in the first room but in the last, and it is there that I see the Baag – Quintus Jan Telting – Ron Flu triplet of my first visit. Once more, these three stand out. And of these, Quintus Jan Telting (1931 – 2003) intrigues me most.

He will be the subject of this essay.

First, a few remarks on the conceptual framework of School of Surinam, and how Telting fits into it. The exhibition was initially conceived as a project focussing on the artist Nola Hatterman (1) who, among other things, was an influential figure in the early days of building an art education system in Surinam. This helps explain the show’s title: School of Surinam. The show’s initial concept eventually shifted towards “a broader exhibition of Surinamese art” (2) , incorporating more artists, and ‘school’ to be understood foremost as ‘group’, though not in the sense of an artistic move-ment. The (guest) curators rightly assert that Surinamese art is hybrid, and that it cannot be defined by one overall label. School of Surinam indeed demonstrates that as early as the 20th century, Surinamese artists ventured out into various areas (not only geographical), depending on their individual artistic orientations. Personally, I find this theme of pluriformity more interesting than the historical framework, along the lines of art education, which remains the overarching framework of School of Surinam. It was a happy coincidence therefore that on my second visit I bypassed the prescribed startingpoint and began at the very end, in the ‘proper’ art rooms.

My feeling was affirmed by information in the Reader and the (online) talk about a difference of opinion between Nola Hatterman and Jules Chin A Foeng as to the nature of Surinamese art. Hatterman was criticized for focussing too exclusively on Afro-Surinamese art, while in Surinam, with its diverse population, artists from many more ethnic groups, with as many cultural backgrounds, were active in the arts scene. Chin A Foeng wanted to embrace exactly this diversity of artforms and art traditions. This controversy was new to me and it immediately brought the hybrid nature of Surinames art into sharper focus.

The work of an artist such as Telting fits naturally into a pluriform framework. And, moreover, Telting expands its scope: he identified as a black (Surinamese) artist, and from this position he became involved with black, politically engaged artists from the USA. This is what defined his artistic orientation.

Telting travelled to virtually all continents, where he sometimes took up residence for long or short periods. I am particularly interested in his New York years (appr. 1959-1970). He stayed there during the heyday of the Black Civil Rights Movement. As a black man his everyday life must have been conditioned by segregation and discrimination. As a black artist, one who was in close contact with activist artists of the Movement, among whom was the writer and poet Amiri Baraka (1934-2014), Telting must have picked up on the debate around ‘Black Aesthetics’. Assuming that the concept existed at all, what would it entail? During Telting’s final year in New York this debate culminated in a heated controversy around the very first soloshow of a black artist: Al Loving (1935-2005), in the Whitney Museum. The incident is discussed in the catalogue Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power (Tate Gallery, 2017). Loving was accused by his fellow black artists and critics of being ‘colourblind’ for showing formalist, hardedge paintings. According to his detractors, with such work he sold out to the dominant ‘white’ aesthetics because it ignored aspects that typically mark a piece of art out as being Black art. Loving took the criticism to heart. Over time his work shifted towards a subtly different form of abstraction: not strictly formalist but incorporating aspects and motifs from his environment that helped shape him as a black artist.

I expand on this controversy surrounding Al Loving not only because it cannot have gone unnoticed to Telting but because it helps us place Telting’s work in the artistic and social context in which it was created and seen. Telting’s personal website opens with his motto: “I am an artist and being black, I find it my duty, since I have a gift to create, to create with a purpose…”. This statement, which to me is intricately woven with the issue of Black Aesthetics, is key to my understanding of his paintings, and, in this essay, it is my frame for discussing them.

The Chess Players, photo: GJ.van Rooij

In the first (though actually last) room I see The Chess Players (1973). The painting evokes Rembrandt and Dutch caravaggists such as Hendrick Ter Brugghen, mainly because of the way Telting handles light. It also reminds me of a statement by the Surinamese painter, and friend of Telting, Armand Baag. When a student at the Rijksacademie in Amsterdam in the 1960s, Baag was hit by the thought that he was destined to become a “little Rembrandt” (quoted in the Reader, p. 17). It was an epiphany, and not a pleasant one. Baag’s future work clearly demonstrates that he did not turn out to be a little Rembrandt. Neither did Telting. The Chess Players evokes Rembrandt and the caravaggists but it does so with black figures, and in an altoghether different setting. To me it is that of the domino players in the novel Dubbelspel (1973), written by Frank Martinus Arion (Curaçao (Dutch Antilles) 1936-2015), or that of the hot-tempered mahjong players in our neighbours’ yard way back in Paramaribo.

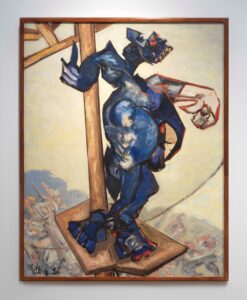

Garbage Rose Containt, photo: GJ.van Rooij

Something about Telting’s post-Chess Players paintings began to draw my attention: it is their specific perspective construction, with a high vantage point that gives the viewer an overall view of the scene from somewhere high up (see also Opus #1481 en Opus #1502). Garbage Rose Containt (1985) is a case in point. From my viewer’s standpoint I look down on a figure which, judging from its face and hands/claws, is half human, half animal. The dots on its left hand and left foot could be stigmata. Barefooted, with colossal (human) feet, the creature balaces on a platform towering high above what resembles a garbage dump (see the title) but could just as well be a distant cityscape. The image simultaneously projects power and a sense of vulnerability. It depicts a strong body in a precarious position. The figure roars, its mouth wide open, with an expression that is pained and dauntless at the same time. Telting equips him/her/it with huge feet but places it on a minuscule plateau. How did it get there in the first place, I wonder. Did it ‘simply’ climb up or was it chased up? The painting offers no easy answers to my questions. I can accentuate different sets of aspects of this King Kong like figure. Logically, these would be mutually exclusive, but not here. The creature is victim ánd in charge, distressed and belligerent, vulnerable and commanding. Garbage Rose Containt presents a complex narrative and I immediately sense that there is an urgency to it. Telting’s perspective on this narrative is not clear-cut, rather he nudges you to thoroughly reflect on the scene he has laid out.

Opus#1502, photo: GJ.van Rooij

Telting’s paintings are contemplative. This dawned on me only gradually, because their dynamism, speed, colour explosions and undercurrent of violence take so much center stage. Telting reflects on emotion rather than painting solely from emotion (a set of emotions that I myself feel deeply). His specific perspective constructions (the high vantage point) contribute to this particular contemplative characteristic. A high vantage point can have a psychological impact – ‘looking down upon’- but basically it places the viewer (and Telting, I presume) above the depicted scene. This subtle intervention persuades the viewer to put their initial reaction on hold so as to reflect on the confronting scene ‘below’ them and how they relate to it.

In my view, another theme in Telting’s work is reflection on painting itself. On his website I see a number of paintings that point in that direction: Opus #1444 (1984), Opus #2028 (1991), Opus #2407 (1997) (3). As an artist, Telting’s inclination was unmistakenly intellectual. A friend of Telting, Bob Schoo, provided me, during a conversation, with valuable information on Telting’s personal life. The first thing that came to his mind when characterizing Telting was that he was “a thinker”.

Telting is by no means a pleaser, and this attitude pervades his approach to painting. His lines tend to be rough, sketchy, while his shapes are angular and sharp-edged. On Garbage Rose Containt, for instance, the top and bottom sections in the background are separated by a rough, jagged edge. The larger, grey-yellow plane is rendered practically without depth. It is only due to a shift in colour, from a muddyish grey, bottom right, to a clear light, top left, that this colourplane becomes space rather than a flat wall. Telting’s uncompromising style is all the more foreboding in relation to his motto, which I quoted above: “I am an artist and being black, I find it my duty, since I have a gift to create, to create with a purpose…” He identifies and expresses himself as a black artist. In that context, and in the era in which he was active as an artist, ‘to please’ is not an option. Telting is uncompromising when it comes to this.

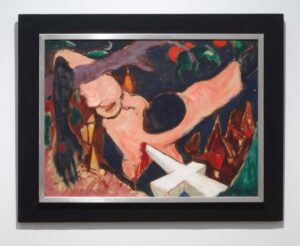

What Is It That the Christian Hides Behind?, photo: GJ.van Rooij

In What Is It that the Christian Hides Behind? (1970) Telting once more resorts to a high vantage point. The viewer looks down on a figure. In this instance it is a man who is suspended from the branches of a tree and is pierced by a cross. Telting leaves no doubt as to how this man came to be in the spot he is in: he is the Strange Fruit of the lynchings in Billie Holiday’s well-known song. ‘Real’ fruit is painted next to the man. The colours light up from the canvas: the pink of the man’s clothes against the intense white of the cross; the blood red stain on the man’s body. The red stigma on the arm that is suspended over the branch, and the exact spot where the body is pierced, are references to Christ on the cross. The Klu Klux Klan is present as well, in the triangular reddish-brown shapes, bottom right, and, more obviously, in the luminous white cross, an echo of the KKK’s typical flaming one. To me, What Is It that the Christian Hides Behind? is Telting’s most straightforwardly confronting work.

What Is It that the Christian Hides Behind? is one of many paintings in which Telting zooms in on the body: Telting depicts the body pierced, lying prostrate, dangling from a tree branch, hovering above an abyss. There is no ambiguity to the violence inflicted on the defenceless body. It is actually a theme with a long history in the canon of Black literature and art. The classic novel Invisible Man (1952) by the black author Ralph Ellison comes to my mind, as does the more recent Ta-Nahisi Coates book Between the World and Me (2015), which opens with “Son, Last Sunday the host of a popular news show asked me what it meant to lose my body.”

Opus #1481, photo: Aldo Blom

In Opus #1481 (1985) two figures are facing each other in a David and Goliath fashion. One is huge and wears a military-style outfit (he also strikes me as a comicbook style American football player, with headgear, shoulderpads, and ball). The other is an undersized creature whose outfit is more informal, but the matching cap and pants in pastel colours point to, perhaps, a specific historical army uniform (or to a rival team’s outfit). I cannot gauge the exact relationship between this incongruous couple. The figure on the left outsizes the other, but there is something ridiculous to his appearance. My perspective is triggered by the posture of the smaller figure, who is gesturing wildly in an effort, so it seems to me, to make a point – “hij is vrijpostig”, an older generation Surinamese person would say, meaning “he is impertinent, cheeky”. Does Opus #1481 depict an image of bully and victim? If it does, I can’t be sure which is which. In any case it offers a complex and multilayered image: an innocuous game (chess, football) can escalate, and violence can jump from the instigator to the one who is the recipient of their agression.

Telting’s paintings are topical and relevant in their own right. I have discussed them from the point of view of Telting’s commitment as a Black artist, and I have linked his work to the concept of Black Aesthetics. I take it that, once his work is juxtaposed to works from the Stedelijk Museum’s permanent collection, new relations, perspectives and cross-pollinations come to the surface, and will continue to do so.

© Dineke Blom, June 2021

Postscript. Why is there no proper catalogue? On my first visit I could not find anything of the kind. I remember it vividly because I had difficulty believing the sales person in the Museum store. Now, a printed version of the online reader is available. But why are there no images with the captions, if only these were thumbnails connecting text to the paintings? In light of the Stedelijk Museum’s ambition to place Surinamese art within an arthistorical context, it is very urgent for School of Surinam: Painting from Paramaribo to Amsterdam to be accompanied by a proper catalogue, in print, and with visuals.