For me as an artist, I want to be known as an artist, at the end of the day I want to be known as a human, I just want to be respected. But sometimes I choose for African American artist, in many ways we need to be acknowledged for our contributions to the world. And I think we have given a lot of contributions and a lot of them haven’t been acknowledged.

Rob Perrée interviews Radcliffe Bailey

Nest, 2012 (detail)

In my work where I try to make something that is peaceful.

An interview with Radcliffe Bailey

Last year Radcliffe Bailey had an exhibition in the Maruani Mercier gallery in Brussels. The gallery owners asked me to have a public interview with him. Since I like his work a lot and since I wanted to select a number of his works for the TELL ME YOUR STORY exhibition I curated for Kunsthal KAdE in Amersfoort, The Netherlands, I said yes to the invitation.

Luther Goines Cosmos, 2019

This is not your first visit to Brussels?

I was visiting the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren. In 2011. There was a thought about my work coming to the museum. That visit informed me in a different way of understanding and looking at African art. In a different context then I’m used to seeing it in the States. I always enjoyed going to museums, especially to museums that have older objects. One of my fascinations as a student in art school were all the places where I would gather material from like antique shops. In doing that I was able to step back in time towards a period that I didn’t know much about.

Atlanta is important for you. Why?

In a strange way yes. I was born in New Jersey but in 1972 my parents moved to Atlanta. I didn’t know and understand why. My mother was interested in history. That I know. She would take me to different places. As a kid I went to a guy that created uses and practices for a peanut. He had a lab at Tuskegee university. I visited him there too. I went to those kinds of places. The property I live on is old civil war ground. Some of the troops camped out in the woods where I live, before they burned down the city.

Atlanta has been this place where it’s been building over old structures. For ever going, never knowing, as we say in Atlanta. Dealing with civil war, civil rights movement, I grew up with a lot of kids whose parents where civil rights activists. My parents were more from the countryside of New Jersey. On my father’s side we go back to the Underground Railroad which took run-away slaves to freedom in the North. So I am surrounded by my history.

Do you want to solve things by going back to history?

I use my studio as a church. I’m not a religious person, more a spiritual person. My practice is more like a search of the solution of problems we live in today. I watch the news and I’m constantly irritated to the point where I feel like I have to make work that has a more spiritual presence. In that way I’m trying to solve problems, in the middle of the night.

You also use material that has a history? That goes with it, is it a logical choice?

Right. For instance, right before my grandmother died, I remember she gave me 400 photographs of family members. They were from around 1910. We didn’t know a lot of them, but my grandmother wanted me to be the keeper of the photographs. I can respond to those images to make work. Sometimes there is a lot of truth, sometimes there is a lot of fiction. I work within that space.

What surprises is me is that you use private material and you turn it into something global?

Right. I hope to, I’m not sure if I do it but I hope to.

You lift it to a universal level.

I try to. I’m not sure if I do it

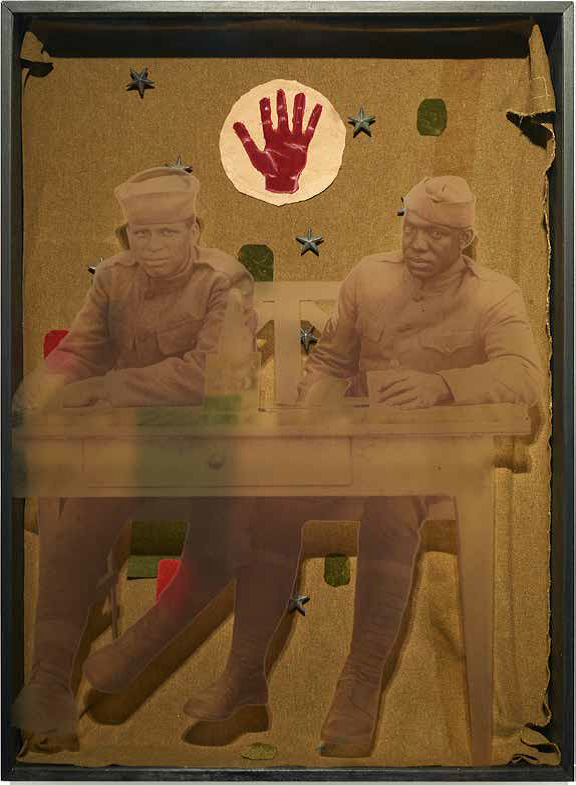

Stars Over the Argonne Forest, 2019

Can you give examples?

Like that one on the wall right there was during the WO I. African American soldiers fought in the WO I. That is almost like fighting for…. like a man who has no land, or fighting for a country that not necessary loves him. I see those images a lot. I have images from the civil war. I don’t necessarily have a destination of thought. I put it in such a way as to bring more answers as opposed to me knowing why. The main reason why I do it is because I’m curious.

It was always hard when I would make work that was personal or of my family and then put it inside the context of a gallery or another exhibition space. My first attempt to do it felt very uncomfortable, it felt like it was just personal, not more than a family photograph. But then I realised I was preserving it in a way and that is kind of my goal.

Every new work is related with the one you did before? As if it is a continuation or a big installation?

That’s the way I work. I’m making work and I look at it as a book, so every painting is a page, there are more and more pages, so it’s going on and on. I work with thought but I continue on and I go back to older objects or sometimes figures become deities, they come back again. I use them at a certain moment when it feels appropriate.

People try to categorise you as an African American artist. I think that you don’t like that?

No I do. It just depends, how it’s used. I think African American artists are hard to define. We also want to be identified as American, we want to be part of the bigger picture. But we also want to identify ourselves in a particular way. Number one we don’t exactly know what part of Africa we may have originated from and plus we also mix with many people. And it’s complicated to be treated in a particular way because of the color of your skin. Today I want to be seen as a human, as a person that has just as much voice as anyone else. But it’s also hard for me to talk about parts that are not necessarily acknowledged and that is the part of having a relationship to Africa. There is a separation by an ocean. It’s complicated.

We were once called negro, black, African American, it’s hard to not really have a land that you can call your own. That’s where its gets complicated. For me as an artist, I want to be known as an artist, at the end of the day I want to be known as a human, I just want to be respected. But sometimes I choose for African American artist, in many ways we need to be acknowledged for our contributions to the world. And I think we have given a lot of contributions and a lot of them haven’t been acknowledged. Part of it is being living in America. Which is strange.

Installation view The Ocean Between, Brussels, 2019

Do you think there is a change of how African American artists are being treated as opposed to when you started?

Yeah I think it is different but then also we speak different languages among ourselves and we are very diverse. We speak different languages, we see it in different ways, we live in different places, we have different approaches towards subjects, some artists are more political in such a way. I find myself trying to deal with the history and the pains but also wanting to deal with the beauty. I am really fascinated with beauty and love and love of oneself. And I’m really about trying to deal with that. I often work with layers, often with seven layers because I never know when to finish, but a lot of the layers have to deal with some of the complexities with who we are as well.

Is that also the reason why you use a lot of symbols?

Yeah, I use a lot of symbols that exist in certain parts of the United States that are not necessarily talked about and looked at in the same way. There are certain signs of architecture that was made on plantations, made by African Americans on plantations, that you could draw some connections to Congo. If you could draw some connections to different parts, you could see it in a more natural way. You can see the same things with musicians. You can say James Brown and you can talk about Fela Kuti, you can say Ali Farka Touré and you can talk about John Lee Hooker. Those rhythms and that space right there in between the two that I find to be very important and that I want to put in my work. We live in a different time, where things disappear. We live on Instagram and Internet, younger people don’t necessarily have the same connects, especially in popular culture.

By using those symbols, don’t you make it more difficult to understand your work?

I don’t respond or react on what someone thinks. I am not really concerned about what someone thinks. It’s more personal, this is what I think.

Nest, 2012

Talking about symbols, can you talk about the work behind us?

It’s a strange work. It’s meant to be like poetry, being poetic. When I was a student I was a sculpture maker, I made things in steel. I loved music also, music was the closest connection to my DNA. I was very curious about sounds and rhythms from across the world, so here I deal with piano keys. People have touched those piano keys. They play all kinds of different music. Classical music, jazz music. Sometimes jazz musicians rip up the classical music and bring it in a different way, create something totally different. The bird, the stuffed falcon I use sometimes. In this case I was fascinated with the falcons and hawks that would fly in my backyard. Often I work in the middle of the night and sometimes I hear weird sounds of birds. Eighty percent of my time I listen to jazz music and respond to it.

Double Consciousness, 2019

Your work reminds me of the work of Terry Adkins

There are a lot of older African American artists who use jazz music as a glue. He was one of those artists that did the same. There was also David Hammons. For many older artists, parts of the Black Arts Movement, jazz was an important art. I think in many ways they did not necessarily want to divide the music from the art. But the art brought it back together in a certain way. But yes, Terry was a friend. I was introduced to him based on the way we work.

You made a series of works about the Africa museum in Tervuren. Is there a specific relation with that museum?

In 2011 I was visiting the museum and I noticed so much African art that hasn’t been seen. It fascinated me in a way. There are museums with African art where the collection sits out in the same place all the time. It’s always interesting to see African art in a different context. It’s more about the reaction to African art when I see it in a museum. It’s interesting to see how African has travelled its way and influences and affects people in different ways.

You use the African object or image in a completely different way? You do more justice to what it is?

I think so. I’m having a private conversation with it. Sometimes it seems surreal. But I also think that our experiences are surreal. Just to understand my family’s history, crossing the Atlantic, not necessarily knowing the position of trying to recover our history. That is where my brain goes when I work with it. And it’s also really about the beauty. I can’t explain the practices and the things that were happening, I know what I know from what I read, but I also take a different approach where I look at it. I spend time with it and I think about it from an artist’s perspective.

You were laughing when we talked about it before the interview. What does it mean to be an artist under a Trump presidency? I am just curious. How do you deal with that?

It’s kind of like humorous every morning, it’s sad and depressing and humorous in the morning when you hear about all the crazy tweets and craziness, you scratch your head and you say I can’t believe this guy is doing this, it’s almost that I have to shut it out. I refuse to let it be part of my work. I do not want anything of that bad energy in my work, in my work where I try to make something that is peaceful.

Installation view, The Ocean Between, Brussels, 2019

Do you have a view on the future?

I think that is a big part of my work. My favorite musician is Sun Ra and Sun Ra is from Birmingham Alabama but Sun Ra believed he was from Saturn. And I sometimes think that when you bring things, sounds from the past and the present, when you put those things together, like in hip-hop culture, where we do sampling, we use music from our parents and we put that music together and change the rhythm of it somewhat like in the collage culture, we put things from different time periods together to make something that is more futuristic, that takes us and transports us in a different space, gives us a different sound or rhythm. I hope to do that with my work.