“The color and form may illustrate moments of sorrow, happiness, hope and despair, but the most important element is that of nostalgia for this universal world which is truly a reflection of my career. Thus, through my art I am most concerned with universality. Art for me is ultimately the connection between human beings. Art is what sustains cultures and indicates the material aspects of civilizations and as human beings we are responsible for this task”

Mulugeta Tafesse quotes the Sudanese artist Rashid Diab

Rashid Diab

PAINTING A MELANCHOLIC TRUTH AND ITS SUBLIMES

Truth has its endless accounts to tell, even in art, which starts from a false foundation and, can’t be quiet often adequately described by words – the characteristics of its special sublime – it can’t be literally contained. If you describe it, you’re then doomed to fail, as it is a nonentity as the sublimes’ most fictitious truth on a two-plane figure – flat surface, ‘a voguish craze (!)’ a hipper may reply exclaiming his find, but it’s different from that. And consider my librettos! It is unlike any other thing! Not a few people wander to fulfill their dreams and artists ramble through them – to trace their truth, to find the missing thread of their half-done oeuvre d’art (nouvelle), their New Age Style(s).

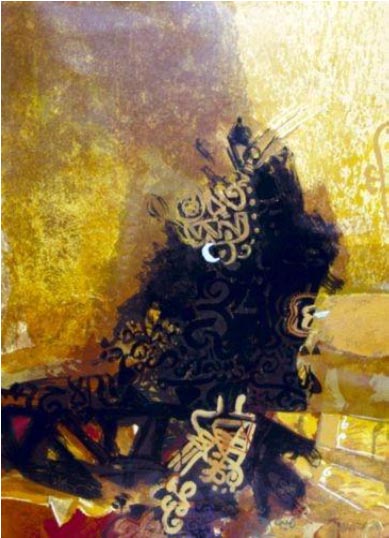

Like one of these artists’ oeuvres we mention by heart, Rashid Diab’s art configures that, as a born poet and a pacifist Diab happened to pick the painter’s enigmatic device. The painter’s palette. It is his unconditional destiny, and he has the perfect philosopher’s mind to resign from it (whenever he needs to), from its joie de vivre. Let’s for a while trace back Diab’s past, his nightmares that he hasn’t solved out; nonetheless pushed the limit as best as he could, as what the toughest chi can achieve. I have followed his enlightening artistic voyage for nearly twenty years now, and suggest, from now on you do the same. We as artists and creative folks can learn from such marvelous personalities’ lives and professional encounters.

Now let me walk you to the cutting-edge culture insides of an East Africa metropolis, Khartoum. If you are suddenly heading towards the Khartoum international airport, you should very much pay attention to the roadside, because you might be passing the Rashid Diab Art Center in Khartoum. (RDAC) On the very spot where this center is located anyone could see the presence of a new white edifice fitting to a peaceful garden and a small corridor alley lined by its side. The garden intersected by a small pathway leads us to different sections of the new building. People can immediately sense the subtlety of ornament interlaces – interior to exterior – in the architectural items made from plaster and greeneries that are aligned to each other’s benefit. Hence visiting this edifice and its contents inside, anyone can straightaway feel the manifestations of a master hand.

No one would doubt that a certain architect and designer, has stupendously left his/her outstanding aesthetic marks there. That is the soundest guess one can arrive at while looking this unique Khartoum culture edifice and its aesthetic vow. The whole idea about the entire aspect of this multi-functional art center called RDAC (an acronym for Rashid Diab Art Center) is to merely give cultural cordiality to those who need it. The center was founded by the Sudanese international artist and art-theorist Rashid Diab (Ph.D.) who has made Khartoum once again his earnest home and vibrant work place, a proving “comeback”, I think, thus to give truly the city of Khartoum what it deserves most and was missing much: Art.

The travel of the artist across countries and cultures

Art is a social medium, not a nonsense exercise – one must garner it working hard. This is unspoken but true and it is Rashid’s and other African artists’ belief.

We should perhaps adopt the belief of the Sudanese public too, which is also the content of Rashid’s art, and try to analyze his ‘cultural activism’ (my paraphrased term) as well, by seeing his recent activities. Nearly all the web materials (1) reiterate for example, the next piece of his stories: “for a long time painting was a topic in the famous “Khartoum School of Art” in Sudan, but it is only Rashid Diab who started to earn a living through it by founding his own art center”. This news I gathered from the social medias, adds also Diab as an organizer of great cultural events. A respected intellectual, thus a heeded voice, Diab was also behind “Khartoum, Cultural Capital of the Arab World 2005” initiative. Influential in the subject of art education on the national level highlighting how important art subject is in the general education. Rashid Diab encouraged his compatriots to publish magazines and books of art and design, and set even a plan for an art museum, the last, which unfortunately hasn’t been realized. (2)

Rashid recognizes that the Khartoum School of Art, which trained so many famous Sudanese artists working in Sudan and worldwide is the only College of Fine and Applied Art among about 40 universities in the country. (3) This school, Diab reiterates, which is under the Sudan University of Science and Technology autonomy in Khartoum is also the place, we now know where all Sudan’s internationally recognized artists, like Ibrahim El Salahi, Khamala Ibrahim Ishaq, Hassan Musa and others have come out. The Sudanese art historian and curator Salah M. Hassan points as to when the Khartoum School (movement) was established (4) (we shouldn’t confound here the Khartoum School of Art, which is a government institution with the Khartoum School, an art movement). Hassan also says, the real breakthrough within this new tradition came in the late 1940s and early 1950s with Ibrahim Salahi and his colleague Ahmed M. Shibrain with Magdoub Rabbah and Taj Ahmed, among others, who led a distinct new movement, which evolved into the Khartoum School. (5)

A creative youth: First paces, search for art – movement onset . . .

Rashid Diab was born in 1957 in Wad Medani Sudan’s Gezira Province – on the banks of the Blue Nile. He painted during childhood while later joined to study in the College of Fine and Applied Art, Khartoum. He got a government scholarship to Spain, which latter proved to be highly significant as it helped him develop his early-discovered talent. He received his M.A. in graphic Art, M.A in painting and Ph. D in painting respectively in 1984, 1986, and 1991 from Compultense University, Madrid. He stayed in Madrid after completing his studies practicing painting and graphic art and worldwide exhibiting. (6)

Travel I: moving to Spain in the pursuit of knowledge

Rashid’s choice to study in Madrid was unusual, regardless of most of his compatriots’ interest that followed their art studies in the UK or the US. One can read from his many interviews that he hasn’t been to England only to express his wishes and get a particular foreign experience, but he went to Spain granted a scholarship from the Spanish government and he discovered there a different education in the visual arts. He participated in several international exhibitions and major art biennales, among others, “New Visions, Recent Works by 6 African artists, Rashid Diab, Angeli Etoundi, Essamba, David Koloane, Wosene Kosrof, Houria Niati, Olu Oguibe” in the US; Johannesburg Biennale, in South Africa curated by Okwui Enwezor and Olu Oguibe and also in Havana and Shahraj Bienalle, respectively in the Cuba and the UAE. He received numerous awards from renowned art museums and foundations – this could be seen in most of his art catalogues (among which I keep two since 1997) and in the Internet media from which I quiet often update my information on East African Art.

Rashid as an international artist, traveling globally – from Havana to Seoul, from Johannesburg to London – he had with noble reason to share wise words with the Korean art public when his show travelled in 2009 to Seoul, the South Korean capital. In an interview to the Korean Times, he pressed on art’s progressive values as he opined to the public the subject of his art. His focus was not only his paintings and graphic art prints per se, although he explains his art well, but the visual arts culture impact in general, the humanist contention, which theme alludes to universality (7):

“The color and form may illustrate moments of sorrow, happiness, hope and despair, but the most important element is that of nostalgia for this universal world which is truly a reflection of my career. Thus, through my art I am most concerned with universality. Art for me is ultimately the connection between human beings. Art is what sustains cultures and indicates the material aspects of civilizations and as human beings we are responsible for this task”

Deep Summits (II), graphic print, serigraphy on canvas, limited edition, 1997.

Deep Summits (II), graphic print, serigraphy on canvas, limited edition, 1997.

Painters touchdown on the locale soil, is it a measured repose?

Travelling throughout the world as all celebrated artists do, Rashid Diab has internationally garnered a respectable experience that is readied not by many artist voyageurs. He has travelled from Spain to Middle East, and from America to Far East Asia. While in Spain, although he has practiced painting and graphic art, lately, he has laid his hands on a number of art practices; including interior architecture, design and other arrays of artistic expressions, i.e., object, furniture and fashion design. One can even see Diab lecturing a big audience wearing his self-designed stylish Galabiya. (8)

“He wears his styled “Rashid Fashion” collection – primarily artfully embroidered Galabiyas and scarves for the turban in its own design, which are produced from Sudanese cotton fabric from a company in Sharjah (UAE).”

A certain blogger here continues detailing the beauty and functionality of the Rashid Diab Art Center RDAC, which she has visited. Therefore one can guess, that plan the center perhaps started earlier in his privately run Dara Art Gallery. From then on, it surely has culminated to the final art center that opened in the summer of 2006 near the international airport in Khartoum. The blogger writes: (9) “(….) Diab built it continuously into a veritable place of art and culture, which now became the popular “culture temple”. The same blogger explains that even the entrance to the center reveals a work of art. It is the artist’s work, behind which benches are laid on a mosaic floor in which one may constantly discover new ideas.

“The building was not left to chance. Whether in the domes form, the balconies, hand-painted glass windows’ and the garden’s design you are surrounded by art works. RDAC is the only place of its kind in the country, and reflects the openness to the world of the artist and holding his Sudanese roots and commitment to young artists.”

From this news one can understand indeed Diab has done a fabulous job to the visual culture craving Khartoum public in particular and the Sudanese youth in general, which is in search of its identity. Imaginatively uplifting and enriching artistic pits, creating creative spaces is not in short supply to Rashid Diab as I witnessed through his released videos in the YouTubes’ Ted-X speeches and his tutoring children. The young need everywhere an artist guide or bold words and clear images from their unsung models. And like those present models, generous mentors such as Dr. Rashid Diab make available themselves at almost every venue and time.

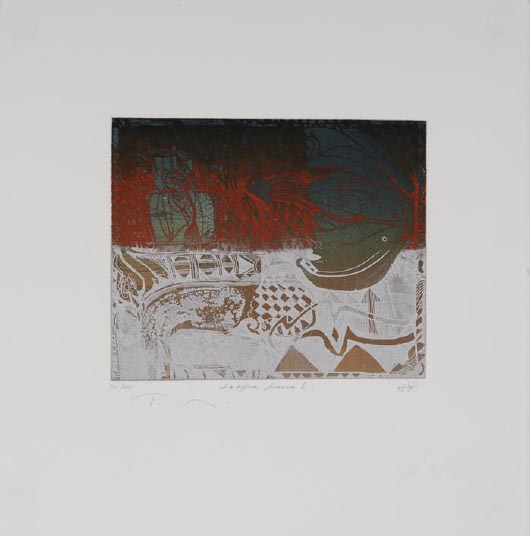

Spring Sounds, graphic art, serigraphy on canvas, limited edition, 1998.

Spring Sounds, graphic art, serigraphy on canvas, limited edition, 1998.

Travel II: People wander to fulfill their dreams and artists ramble to trace them

The Guardian culture page about a decade ago released a long article written by one of its reporters, James Astill, on the great successes and also the offbeat challenges of Rashid Diab in the new Sudan. This was a few years after his arrival from Spain, and the paper even remarks about Diab’s travel in Sudan’s northern deserts: (10)

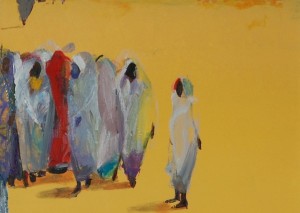

“Diab set out to rediscover Sudan on a lengthy tour of its northern deserts. The result is an impressionistic series of shrouded women, their faces turned away from the artist. The loose folds of the cloth, suggesting but not quite revealing the curves of their bodies, recall something a female Somali friend once said: “Don’t look at how much cloth covers the skin – look at what you see through it.”

James Astill also writes about the modern artistic mastery of Rashid Diab, which no body who knows his art doubts that the latter is it’s authentic claimer and to certain extent, also it’s independent mixer (with Sudanese artistic and cultural norms). (11)

“Most of the writing about Diab’s work dwells on whether he is an African or European artist. The usual conclusion is that his is an African vision through the lens of European technique. Diab himself has no time for labels. “Technically, I suppose I’m a European painter because I use an easel,” he says dismissively.” (12).

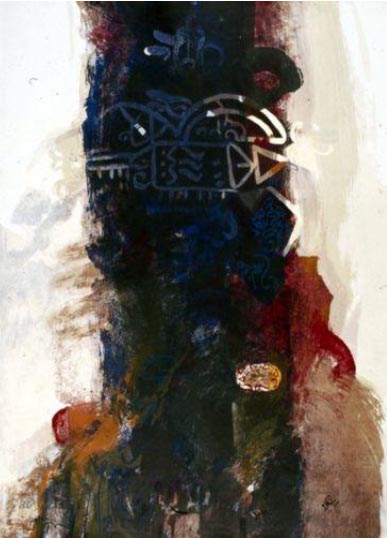

Deep Summits (I), graphic print, serigraphy on canvas, limited edition, 1998.

Deep Summits (I), graphic print, serigraphy on canvas, limited edition, 1998.

Deep Summits (II), graphic print, serigraphy on canvas, limited edition, 1998.

Being now the RDAC is also a residence to travelling foreign artists who want to do a tour like Rashid and reside and work at his center’s creative base, it appears the visionary Tayeb Saleh’s novel remark is grounded (mind but in a positive note!), – has come to fruition. Here I’ve taken a reference from the internationally acclaimed Palestinian writer Edward Said’s writing on this issue in my Ph.D. thesis about a voyage in search of truth or/and discovery: (13)

“To what is loudly read on the minds of Non Western writers, in aspects of stereotyping the other – as downgraded and primitive – an opposite version of the story is observed by the Palestinian scholar, Edward Said when he tackles this issue of Conrad in the Heart of Darkness. Said indicates rightly the ‘other way’ writers, like the Kenyan Nguchi, and the Sudanese Salih Tayeb, ’appropriating for their fiction such great topoi of colonial culture as the quest and the voyage into the unknown, claiming them for their own, post-colonial purposes’. (Said, Culture and Imperialism p. 34, 1994)”

Salih Tayeb’s hero in his roman ‘Season of Migration to the North’ travels to the North to his exotic destination as his counterpart hero, Kurtz from Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Africa would do, to face the unwarranted endangerments. (…) Tayeb’s character faces problems as expected taking the reverse (a voyage to the North) of Kurtz’s Central Africa. The North can be just a terrifying place as Kurtz’s Central Africa. (14) ‘Salih’s hero in ‘Season of Migration to the North’ does (and is) the reverse of what Kurtz does (and is): Black man journeys north into white territory.’

Back to Dr. Rashid Diab’s time precursors – European to African time intervals and space units. It is here however, Rashid Diab gets on in one’s travel and journeys – his travel and journeys had the same bind – may be restorative remedies to nurse the soul, and art is part of it, in search of truth using this medium and space value that the artist has to relinquish his needs with. This is what one could condense from Diab’s several interviews oftentimes available in the blogosphere and from his Center RDAC’s website:

“Since I was a small child, I have loved to travel. I always wanted to be somewhere discovering new places, different types of life and other people. I constantly thought of how I could create a real and intimate relationship with distance and space. Why do things have specific dimensions and a certain shape at a certain time? These questions became an obsession with the only solution being to paint and continue to paint.”

The RDAC regularly runs workshops accommodating the need of international artists participating in the various activities of the RDAC. This center offers artist-in-residency to those who applied for it and get it. The workshops in the center look fully equipped with art materials that are standardly to produce diverse artistic activities.

Travel III: Homecoming and a brief outing

A great timeout for the established artist could be perhaps the number of invitations s/he gets through galleries, cultural and political institutions, etc., We can nowadays stumble upon on the internet to visit every artist’s website and see who’s done what. It’s how a reputed artist manifests his/her ingenious performances. The number of travels and invitations to important cities and major art centers matter. I’ve met Rashid Diab in the ARCO Art Fair in 1997 [?] when Internet media did not have developed yet, however then very few people communicated by e-mails and unfortunately we weren’t one of those. I was very pleased to have met Dr. Diab and also to receive his exhibition catalogs. Both of us visiting the famous ARCO Art Fair in Madrid, it seems, in the back of our eyes we never stopped tracing our African natives wherever they stop by. Hence our meeting highlighted this occasion. And I immediately agreed to visit his studio afterwards after his invitation. We met just like that as people meet in the everyday, in the streets, etc. I visited his studio first and later his home and I was introduced with his family. It was an immediate reunion of East African artists in Diaspora. He showed me his works at his busy studio, which was full of paintings and graphic art prints, and posters of his exhibitions were displayed on a long corridor. There was a fresh smell of color coming from the solvents and paints. This was a sign that he regularly goes to work in his studio. That is how I’ve collected from him also some art catalogs, which artist’s CV section indicates his extensive international travel and numerous exhibitions.

The Empty Sphere, engraving print on canvas, limited edition, 1997.

The Empty Sphere, engraving print on canvas, limited edition, 1997.

More recently, about 10 years after his move to Khartoum from Spain, in 2009 Rashid made a show in Seoul. Rashid’s exhibition there consisted twenty-one works. They were on display that offered a glimpse of Sudanese culture. His work is said to be a reflection of “a synthesis of his Sudanese heritage and an awareness of contemporary artistic developments in Europe.’’ Here is what Rashid had to say about his works: (15)

“The color and form may illustrate moments of sorrow, happiness, hope and despair, but the most important element is that of nostalgia for this universal world which is truly a reflection of my career. Thus, through my art I am most concerned with universality. Art for me is ultimately the connection between human beings. Art is what sustains cultures and indicates the material aspects of civilizations and as human beings we are responsible for this task (….)”

Gwen Thompkins, on the other hand, an American news agency correspondent in Khartoum’s Diab studio is pondering whether the works of the artist is convivial and exciting enough to her newsreaders as the Sudanese claim it to be. She writes in the NPR journal: “After massive (Ph.) years in Madrid, Diab moved back to the relative quiet of Khartoum in 1999. In a way, he’s here to do what Picasso did in Spain in the 1930s. Taken together, Diab’s paintings amount to a kind of “Guernica” for the people of Sudan, and Thompkins continues: (16)

“But while Picasso’s painting was meant to sound the alarm of war in vivid and even grotesque brush strokes, Diab says the people of Sudan respond to different images. He says the punch of his paintings comes in having Sudanese people see themselves suspended in absolute nothingness, without context or reference to any living thing. It’s what makes his work both beautiful and terrible.”

Diab’s statement to Thompkins in 2007 metaphorically speaks about his subject as to why he frequently uses the female image. (The reader must also note here what questions Guardian’s James Astill has raised, earlier in the text, to Diab in 2001) The woman disappears in the wildernesses, although wearing her wind whooshed colorful saris that dot the desert landscape. Diab’s women, or ladies, let’s call them ‘Ladies’, because they have personalities and poise, look confident but standing desolated in the middle of nowhere. They echo the state of the primordial being in their ancient land. Their presence has an obsolete meaning; however they strongly remind viewers they have unabashedly their lives to live.

Diab says, “Just being alone is a problem. Being alone in the space, biggest space without knowing where you are. This is a problem. Being the public stuck in a way, the woman is a problem. I mean, this is – this entire together but with a nice very prophetic conception of artistic vision”. Speaking about dignity we should speak about news that played its part in Diab’s life. The story of a child whose human dignity was stolen out of him by a natural tragedy and by news crazed world. Thompkins reflects here about a single but famous image that once has seized the minds of the international news media and the art world by droves: (17)

“Only an artist can think of depicting human suffering with a nice aesthetic. But consider the image that brought Diab back to Sudan. It was a photograph of a hungry Sudanese child being stalked by a vulture on the desert floor. That exquisitely rendered shot won photojournalist Kevin Carter a Pulitzer Prize. It brought new international focus on famine in Sudan, and it moved Diab to buy a one-way ticket home.”

Diab is almost speechless, to respond here to Thompkins’ inquiries, which exceed gratitude. He had no immediate clear message to her interview with him on this menacing matter that took place in Sudan when its civil war struck its regions. He had no a simple antidote to react. It is clear for him to respond like that anyway, by saying nothing, and feel only succinct after reviewing this tragic period’s story, which he knew and dealt about it hence forth – by moving to Africa to be a “caring native”. (The paraphrased, my paramount rhymes to exalt the exceptional action that Diab has undertaken – his ultimate return to Khartoum). As an artist who knows and has learned lots of things about images, gloomy media news of one’s homeland make one sick – and the world populace is behind you, advocating your cause and propounding your subject, your region, all the same, this story does tremendously affect one. (18)

It is then natural to one to descend in silence for such question. I also distaste recounting the familiar miserable images except act in good faith, as Rashid Diab did, in his art or deeds – moving back. Especially as a visual artist coming from East Africa, which was in the past consistently overcome by artificial problem (caused by cyclic famines and civil war consequences), I would respond in the same way. Diab at the end says this: ‘[….] it’s a terrible photo. What I’m doing here is helping my country. There’s something wrong.’

Thompkins ends her interview with Rashid Diab after positively reviewing Rashid’s struggles and successes in art and also in the actions he bestowed his society, telling them not to let down their greatest dream in life. Thompkins writes: (19)

“Somewhere in all that nothing Diab likes to paint appears to be another more encouraging message. It’s embedded in his rambling esoteric art center, in the national art competitions he sponsors, in his classes for children, his exhibit space for fellow artists, in his gardening and primers on art. He seems to be encouraging his fellow Sudanese to feel something as primal as the love between a man and woman, and that is love of country, the entire country. In Sudan, it maybe the rarest love of all.”

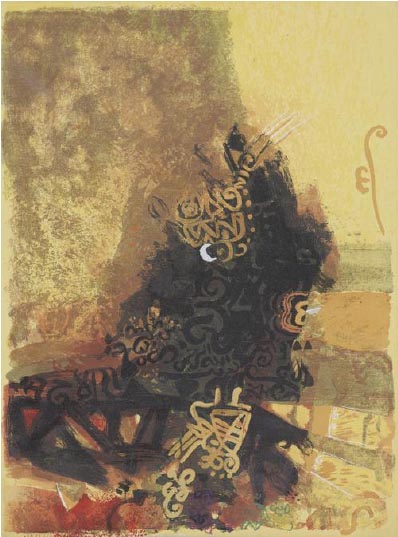

Memory Ech0es (II), graphic print, serigraphy on canvas, limited edition, 1998.

Memory Ech0es (II), graphic print, serigraphy on canvas, limited edition, 1998.

In his critical contribution to the Frieze magazine, Nigerian internationally acclaimed writer and curator, Okwui Enwezor reflects about twenty years ago on the show and the installations of ‘Africa 1995’. (20)

“Perhaps the Sudanese and Ethiopian sections curated by Salah Hassan showed the greatest promise. Two powerful works by the Sudanese master Ibrahim El Salahi – The Last Sound from the early 60s and The Inevitable (1984-85), a work of skillful manipulation of line, volume and mass, depth and shallowness – conspired with the enigmatic, gridded and circular pictograms of Kamala Ibrahim Ishaq and the calligraphic and aqueous luminosity of Osman Waqialla to make the Sudanese story the lone section to dislodge the stereotypes that plague modern African art. “

He slightly criticizes the Ethiopian section, anyhow, because the works were put together in a narrow space and distract the public’s sight in some ways. I wonder whether the London’s ‘Africa 1995’ art installations have emulated a certain techniques from Ethiopian living room art and object displays. (This is also my comment as this essay’s author). I can’t answer that except give good speculation thereof. Since I suspected and I’ve read also about this exhibition ‘Africa 1995’ London show, I hinted upon Enwezor’s words, which wasn’t after all granted in bad faith to Ethiopian art, in fact, the opposite. However this is also a problem that frequently occurs in Addis art exhibition halls. Therefore, I advise my compatriot curators and exhibition makers to use their ‘white cubes’, or ‘black cubes’ (cinema halls), their exhibition walls ‘wide white spaces’ (the doubly aforementioned phrases were excessively used in contemporary Western art presentation notions and should be seen as such). If this matter is analyzed, well, this spatial concept may perhaps be appropriated to Ethiopian working conditions. It is then, I like to think, is a good thing. As some of the highly heeded and advanced artist groups’ members would say, ‘let’s us resourcefully exploit spaces that were always the highest statements of art, physically and conceptually taken.’

Displaying too many works in a small space always upsettingly surface to the fore. This is a handicap at best and ineptness at worst in exhibition making practices. Here is what Enwezor said about the Ethiopian art exhibits, ‘the Ethiopian section was a slight disappointment, again owing to limitations of space and the placing of works up against one another. Despite the hanging, Zerihun Yetmgeta’s Scale of Civilisation (1988) successfully reinvents traditional Ethiopian scroll painting, affecting an attitude of fragmentation and postmodern seriality while still bending the rules that artificially seek to bisect the traditional and the modern.’ (Enwezor, 1995) He also maintains a different note, further in his remark, owing a subtler importance to Zerihun’s works that involve his own style, mixing the modern and the traditional (using items from Ethiopian scroll painting and also eyeing from African art to African design) with the West African artists’ style, similar to the Nigerian and Senegalese artists that Enwezor mentioned. (21)

“Of additional note in the Ethiopian section were the works of Skunder Boghossian, Wosene Kosrof and Elizabeth Atnafu. If there was any consolation in ‘Seven Stories…’ it was the surprising way in which Yetmgeta’s work dovetailed with that of Nigerian sculptors Ndidi Dike and El Anatsui in the Nigeria section. This cross-cultural affinity and shared language within modern African art also extended to the calligraphic traces and marks in Salahi, Udechukwu, Rashid Diab in the Sudanese section, and Souleymane Keita’s work in the Senegalese section.”

Finally Enwezor is well-found to relate Rashid Diab’s works with those of Salahi’s and Udechukwu’s, since I think also these artists use techniques that appear the same, at least from the surface, although every artist uses his/her own mature painting styles and art imageries. If there is any fitting link between these artists, it could be their spontaneous expressions, their contrast balances in the picture plane and their drawing masteries to apply certain appropriated design forms from their respective countries and traditions. Here is then the long thread of ‘moving cultures’ is detectable relating Diab’s art with El Anatsui and Zerihun’s painting and relief forms. Wosene, Rashid and Salahi’s breathtaking abstract art extract countless subjects from African past, living traditions and their own whims of fantasies of the creative dig, as well.

Memory Echoes (II), graphic print, serigraphy on canvas, limited edition, 1998.

Memory Echoes (II), graphic print, serigraphy on canvas, limited edition, 1998.

I want to conclude however with the soul-searching dialogue set between two exceptionally erudite figures, just like their prior forerunners that I quoted some fragments of their essays here in my text. The Spanish curator and art critic Antonio Zaya and my subject proponent whose works we are discussing now, the Sudanese artist and art theorist Rashid Diab are engaged in a critical discourse that edify many areas, including Modernism, African Art, Pablo Picasso and Miguel Barceló appropriating African art imagery that call on different local visual cultures or Western Avant-garde – it depends the way how you see it. The curator and artist here speak about African art, and other currently pressing subjects; likewise, immigration issues. They have also failed to comment on the relationship of Africa and Europe, which is not a great model. This pair of north-south related neighboting continents is not an ideal one. This is a critique on Europe that African art and African cultural products are seen less significant and museums are not created for them nor display them. The problem is compounded by the fact that there are hardly any working art markets for African Art and design.

Zaya asks Diab to present what are the cutting edge examples:

“The greatest Spanish delusion, breaks is that Spanish integration in Europe should necessarily imply as some politicians see it, the exclusion of the Latino American and the Afro Mediterranean from our rich racial melting pot. Does Spain want to deny its past?”

Rashid Diab responds here putting to the fore his logical argument that is hinged to twosome objectives that Spain is caught in: The first is, it has its own challenges to resolve (as a new democratic country, and it is a test country!); and the second, not to keep at bay its old relations with the Latin America and the North Africa world (Africa Mediterranean realm). Diab answers:

“Yes, it’s the worst delusion. The problem is that, occasionally political thought moves within limited coordinates, in the area of convenience, and opportunism. The problem also lays in the fact that the politicians have tried to alter and wipeout the real physiognomy of culture in order to embrace Europe blindly, to accept its model in every detail. The arts and communication are geared towards the exclusion and ignorance of the south. [….] They do everything possible to try and act as the big southern frontier as if that concept has not been rendered obsolete by technology and the media, yet they scarcely play the role of guardians of the gate. According to the criteria, and to the contrary of what many politicians think, the obligation to act as a supposed southern frontier forces Spain to develop its relations with Africa. “

These were certainly one of a kind, socio-economical, geopolitical, and culturally steeped points made by Diab and Zaya. Although Diab tries to explore all aspects of the subject in an attempt to find a comprehensive answer, he always emphasizes the cultural aspects. He tends to first explore the political perspectives and then relates them to the cultural themes as a way to explain the context of those themes. What can one say about Diab except that part his diligent approach to create these essential thought lines are the critical postulations of a creative person of distinction.

February 2015

1. I’ve seen a number of websites to find out the most recent news on Rashid Diab’s art and life. Although I’ve contacted him in 1997 in Madrid and was able to discuss in depth and breadth about his art, one should also admit, s/he needs to update with the new. Here is one of the website that shows i.e., the most prominent members among the Sudanese, including of course its famous artists namely painters like Rashid Diab. http://oladiab.com/2011/05/28/sudanese-who-made-it-big/

2. See website, http://rashiddiabartscentre.net/sudasite/index.php/permalink/3008.html

3. Hassan, Salah M. The Khartoum and Addis Connections, “Seven Stories: about modern Art in Africa”, Clémentine Deliss – Jane Havell (Eds.), a catalog for a Europe touring exhibition, London 1995, p. 111. Hassan’s footnote (no. 11) in the same catalog reads, ‘The Khartoum Technical Institute (KTI) later became Khartoum polytechnic and is now Sudan University of Technology.”

4. ibid.

5. Ibid. Hassan. Salah Hassan writes the first individual to coin the term ‘Khartoum School’ was Dennis Williams, a Trinidadian scholar and art critic who taught in the College of Fine and Applied Art in the early 1960s. He also points at the ambiguous nature of the term ‘Khartoum School’ as other western art critics then echoed it. Hassan suggests the term as problematic if taken to mean a ‘school’ as the term is used in western art circles.

6. Diab was also fated to research further African Art, as he preceded working on his Ph.D. at the Complutense University, Madrid. He later joined staff at San Fernando Fine Arts Academy in Madrid lecturing until 1999, until his ultimate departure from Spain. He was for many years a member of a number of international art institutions, including a board (advising) member at CAAM’s ATLANTIC, a Spanish Contemporary Art Magazine and The Havana Art Biennale. (See artist’s catalogues, and his long cv on the social media, (Sallah Hassan 1995, Rashid Diab. 2009, etc.,)

7. Rose, Cathy. A. The Korea Times April 17, 2009, Sudanese painter holds exhibition in Korea, Garcia Staff Reporter. On the occasion of Diab’s exhibition “Time Lapse via Color, Shape and Form” opens at the Nuri Gallery, the Korea Foundation Cultural Center, downtown Seoul.

8. See website, http://youtu.be/16OrtLJzIC0, , http://UNcover Sudan Show 05 – Rashid Diab Art Center

9. See website, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=827YiVAqvM4

10. Astill, James. ‘The Guardian’, Happy Days Are Here Again: Sudanese Islamic rulers have gone from smashing up sculptures to tolerating nudes. James Astill meets a painter forcing the change. Monday 5.11. 2001. Also see article on the web, http://www.theguardian.com/culture/2001/nov/05/artsfeatures

11. ibid.

12. Astill, James. ‘The Guardian’, Happy Days Are Here Again: Sudanese Islamic rulers have gone from smashing up sculptures to tolerating nudes. James Astill meets a painter forcing the change. Monday 5.11. 2001. Also see article on the web, http://www.theguardian.com/culture/2001/nov/05/artsfeatures

13. Tafesse, Mulugeta., “Headways in the Art of Mimesis, an Inquiry into the Mimetic Art Repertoire of East Africa”, Ph.D. thesis, La Laguna University, Laguna, Tenerife, Spain, 2012.

14. Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (Chapter I, ‘Overlapping Territories, Intertwined Histories, III, Two Visions In The Heart of Darkness)’ 1993, Pub. By Vintage-London, 1994, p.34.

15. Ibid. Rose Cathy.

16. Thompkins, Gwen. Sudanese artist draws from a Nation’s agony, July 7, 2007. NPR Khartoum. NPR, art and design. Read on the web, hear the radio clip: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=11808202

17. Ibid.

18. This is also my own sad experience. Not only as an artist author of this text I share this sentiment, but also as an Ethiopian neighbor whose millions compatriots were perished by successive droughts and maladministration and the almost uncontrollable malicious malediction of nature. Those calamities robbed the lives of many, so I feel the same like Rashid about it, and I’m wordless, like, I’ve to damn shut up often when I’m asked about this historic incidence.

19. Ibid Thompkins, Gwen Thompkins notes that her article on Dr. Rashid Diab art is not fully edited.

20. Enwezor, Okwui. Occupied Territories, Frieze Magazine, Issue 26, January – February 1996.

21. Ibid.