(…) Rashid Johnson’s photographs are arenas of action, places where people come together and cultures comingle. Seeing in the Dark and the abstractions are deeply personal works. However different they might seem, they both explore the conflicts and convergences of the artist’s race and class, and the dual spaces he inhabits as a middle class Black American. The portraits are encounters that help him to test, and sometimes bridge, the social divides within his life and his community; the abstractions, on the other hand, are an almost Utopian space where the bedrocks of two cultures can co-exist and flourish. Together these two series, made when the artist was very young, laid the foundation for all of the mature explorations to come.

Shelley Rice on Rashid Johnson’s Seeing in the Dark

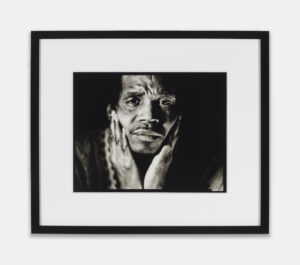

Jonathan (Seeing in the Dark Series), 1999, Gelatin Silver Print, 40, 3 x 50,8 cm

Rashid Johnson

A Different Space of Encounter

Thanks to Rashid Johnson, I’ve been thinking a lot about David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson lately.

These two Scotsmen created the first large collection of calotype portraits between 1843-1847. Hill was a painter, Adamson (his neighbor in Edinburgh) was a chemist/photographer. When Hill was commissioned to make what became known as the Disruption Painting, a work commemorating the break between the Free Church of Scotland and the Church of England, he and Adamson decided that photographing some of the 457 rich and important men (and a few women) involved would be an efficient and interesting way to make sketches for his magnum opus. The painting took 23 years to complete, and it hangs in the Free Presbytery Hall in Edinburgh today, virtually unknown. The photos are a different story.

David Octavius Hill , Newhaven Fishwives, Jeanie Wilson and Annie Linton, 1987.18 – Cleveland Museum of Art

Hill and Adamson made appointments with their sitters and had these distinguished personages pose in ways commensurate with their rank. They knew how to do that, their families had a history of being the subjects of formal portraits; the elite are comfortable and dignified in their self-presentations. But my interest at the moment is in the portraits taken in the off times, when the team had finished their scheduled work for the day and felt like taking more pictures – when they walked down into the nearby village of Newhaven and encountered the people who lived there. The fishermen, the fishwives, the lads and lasses: in the series entitled The Fishermen and Women of the Firth of Forth, there are 130 pictures, salt paper prints from paper negatives, made slowly with a view camera and tripod in the sunlight. The Metropolitan Museum (on its website) calls this body of work “the first sustained use of photography for a social documentary project.”(1) I disagree. “Social Documentary” implies many things, all of them contemporary: that the photographers and the sitters knew their places (and what their pictures meant) in the hierarchy of social images, that the rich men arriving with the camera assumed their privileged position over the people they took the liberty to observe, that the subjects of the pictures accepted this gaze, and with it the imposition of a meaning onto their bodies and their lives. In social documentary, roles are clarified, people become “social types” and images are made to be categorized.

That is not what I see in this series of posed portraits that definitively expanded the range of subject matter in photography. Initially, the medium followed painting’s lead in prioritizing the rich and powerful as subjects. After Hill and Adamson, it was clear that photographs could inhabit a different space of encounter. What makes these pictures so magical is the fact that, as Walter Benjamin said, their sitters “entered the viewing space unfamed.”(2) The villagers, in other words, as far as pictures are concerned, had no history; their image was neither clarified or codified. In this case, each picture became an event taking place between them and the photographers, an event that unfolded slowly, shyly, allowing the mystery of the human face, in all its reticence, to appear. Hill and Adamson didn’t generalize the villagers, make them beautiful, or ascribe them dignity and humanity. They simply looked at them, long and hard, and allowed that gaze to register a meeting point between fellow travelers.

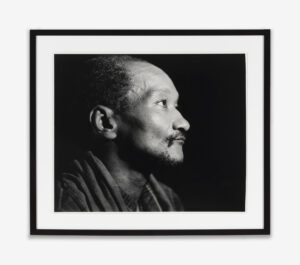

Calvin (Seeing in the Dark Series), 1999, Gelatin Silver Print, 50, 5 x 60,6 cm

It is precisely this open-endedness that makes me connect these 19th century masters to Rashid Johnson, whose 1999 project Seeing in the Dark is a shout out to the early pioneers of the medium. An undergraduate studying photography at Columbia College, Chicago at the time, Rashid (a student of the community-oriented Dawoud Bey) became interested in historic processes after taking a class in experimental photography. This interest was widespread then: Sheila Metzner, Joan Myers, Martha Madigan among others explored cyanotypes and pinhole cameras as well as Pictorialist techniques, seeking alternatives to the fast and facile imagery of the late 20th century. What was unique about Johnson is that he decided to use historical methods – photographing with an 8×10 inch Deardorff camera to create traditional portraits developed using the Van Dyke process (3) to depict the homeless men he met in his Chicago neighborhood. Inviting them out of their environment and into the intimacy of his studio, engaging and recording them, close cropped, in slow time, and then describing them in the rich brown, painterly tones of yesteryear (in ways they would never have been seen historically), he moved them into a different space of encounter.

There was much discussion, during the years when Rashid was in school, about the appropriate “codes” for photographing the less fortunate; social documentary was a contested terrain, and power relationships were front and center in theories by Martha Rosler, Allan Sekula and John Tagg. Johnson was, of course, aware of them, and of the politically correct ways to use the descriptive capacities of his medium. But these rules presupposed certain well-established advantages, hierarchies and identities that were understood and clear. Johnson chose a more nuanced and less traveled path. He was a Black man photographing Black men, in encounters electrified by the affinities and tensions between race and class, as well as varying levels of trust, resistance and revelation. His aim was never to define or clarify his sitters, or to presuppose their willingness to reveal themselves to him. The faces of Jonathan, Eugene and others emerge from darkness, shine forth from the obscurity of the background. The men react to the camera individually, not monolithically; Jonathan’s gesture is even reminiscent of Irving Penn’s interpretation of Miles Davis. Hidden under hats or behind closed eyes, looking to the side or directly engaging the camera, showing their wrinkles, their religious symbols and the weight of their thoughts, Johnson’s sitters perform not poverty but complexity.

Eugene (Seeing in the Dark Series), 1999, Van Dyke Brown Print, 40,6 x 43,5 cm

Johnson’s admiration for Roy DeCarava is obvious in these works. DeCarava’s depictions of the Black experience are among the most introspective in the history of photography: they are, in essence, the embodiment of the private life. Whether seen in the New York City streets or at home, in dance halls or jazz clubs, with strangers or family members, his sitters exude an interior life as deep and rich as their dark skin tones. Teju Cole wrote, “Instead of trying to brighten blackness, DeCarava went against expectation and darkened it further. What is dark is neither blank nor empty…Its subtle implications: that there’s more there than we might think at first glance, but also that when we are looking at others, we might come to the understanding that they don’t have to give themselves up to us. They are allowed to stay in the shadows if they wish.”(4) Johnson’s men have moved off the streets but they are allowed to stay in the shadows, to reveal or withhold themselves from him (and us) as they grow into their images.

Most of these pictures are simple: they show a face, an upper body. There is little detail, but when a crucifix is central to the image or a hat works to both stylize and obscure a face we notice. “Eugene” is almost performative, as it enacts a drama between revelation and resistance. We see Eugene’s face, to the right, at the rear; looking off to the side, his expression is tense, and closed. But the hands pushing forward, large wrinkled palms pressed against the picture plane on the left, dominate this photograph and seem to block our access to the man behind. Are they his hands? Is someone else there? The answers are unclear, clues are illegible in the shadows. Are these hands barriers, warnings that push us away? Or are they reaching out? Or both?

It is precisely this tension – this internal battle – that animates Rashid Johnson’s Seeing in the Dark series and makes it so very special. His homeless sitters lived outside, in public; by definition, they were deprived of a domestic environment, a private space. But enacted within the theatrical space of Johnson’s prints, their relationship (or not) with him becomes an affirmation of interiority, of a complex subjectivity impervious to social degradation. Johnson uses the luxury and antiquity of his medium to work against the “bare life”(5) experienced by his sitters, thus making his technique an active participant in the creation of meaning. This same duplicity is the basis of another early series of Van Dyke prints, in this case abstractions produced at the same time as Seeing in the Dark.

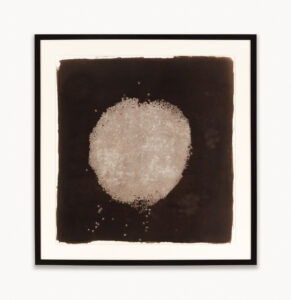

Two of these works, “Beans” and “Chicken Bones,” forgo the human subject to focus on elements of modernist design – but in this case the pictures are constructed by arranging staples of the Black kitchen on printing out paper, and then exposing them in the sun to create negative images. Referencing 19th century contact prints by W. H. Fox Talbot and Anna Atkins as well as photograms by Man Ray and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy made during the heyday of the European avant-garde, Johnson’s abstractions highlight, not the objects of industry, luxury or botany chosen by these photographers, but the most basic ingredients of the African American lifestyle. “Beans” lines up its contents in a centralized (and leaky) circle; “Chicken Bones” allows the recognizable subject matter to cohere into an overall and lively composition. Beautiful and amusing, these prints make a statement once again about the hybrid nature of both Rashid’s art and his life.

Beans, 1999, Van Dyke Brown Print, 68,8 x 63,8 cm

Interestingly enough, there is a well-known body of work by Irving Penn, controversial and admired, which certainly would have been on Johnson’s radar during his student days. Entitled Cigarette Butts, shown at the Museum of Modern Art in the mid 1975, this series was a wild departure for one of the most famous fashion photographers in the world. Close-up and monumental, Penn’s depictions of urban detritus – of used butts discarded and found on New York City streets, then brought into the studio – are sumptuously beautiful. Printed in platinum, they reference the rarified artistic techniques of the late 19th and early 20th century. On every level, these pictures were an egregious subversion of norms, an affront to the codes of luxury and high art; Penn made clear that his intention was to upend the normative pyramid of cultural and economic values. Johnson’s contrast of form and content in his abstract works of 1999 is less aggressive and, as it were, more synthetic than Penn’s. Instead of a conflict, Rashid proposes a merger of the Black quotidian with the language of high Modernism – thereby envisioning a new multicultural space where the avant-garde and kitsch live in harmony and beauty.

In conclusion, Rashid Johnson’s photographs are arenas of action, places where people come together and cultures comingle. Seeing in the Dark and the abstractions are deeply personal works. However different they might seem, they both explore the conflicts and convergences of the artist’s race and class, and the dual spaces he inhabits as a middle class Black American. The portraits are encounters that help him to test, and sometimes bridge, the social divides within his life and his community; the abstractions, on the other hand, are an almost Utopian space where the bedrocks of two cultures can co-exist and flourish. Together these two series, made when the artist was very young, laid the foundation for all of the mature explorations to come.

Endnotes:

1. Metropolitan Museum of Art online, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/268933

2. Walter Benjamin, “A Short History of Photography,” in Alan Trachtenberg, ed., Classic Essays on Photography (New Haven, Conn.: Leete’s Island Books, 1980) p. 204

3. This 19th century, labor intensive contact printing process demands that a negative the same size as the finished print be placed on sensitized paper and developed in the sun. When rinsed with hypo, washed and dried, the technique produces rich brown and painterly tones like those in the paintings of the Flemish artist Anthony Van Dyke.

4. Teju Cole, “A True Picture of Black Skin,” The New York Times, February 15, 2015

5. Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Palo Alto, Ca.: Stanford University Press, 1998) Trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen

© Shelley Rice, Arts Professor, Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, Department of Photography and Imaging andDepartment of Art History,Associate Faculty, Institute of Fine Arts,New York University

Image courtesy the artist and Richard Gray Gallery, Chicago/New York. Photo: Tom Van Eynde.