Tosari is different from his predecessors. He combines different printing techniques in his graphic works, he adds depth and layering. Tosari is conscious that he has to communicate a message, but this does not stop him from making room for detailing and originality. His predecessors were sometimes more limited in their technical options – the early Mexicans for instance –, but they were also often less professional and creative. The visual language of revolutionary printed matter was standardized to a large extent.

Rob Perrée on the graphic work of the Surinamese artist René Tosari

René Tosari

An artist with a mission

Although the phenomenon was in no way new, the nineteen-eighties suddenly saw a lot of activity by artist initiatives. In the Netherlands, in New York, but also in many other countries and cities. Artists organized themselves into groups of like-minded people, because they needed to take control into their own hands. ‘Autonomy’ was the key word. They took a stand against the art world and, usually implicitly, against society. In countries such as the United States the tone of this position was more political than in the Netherlands or Germany, for instance. The initiatives there were mostly against an art world – museums, galleries and art criticism – that was more interested in the work by international artists than that by young, talented fellow-countrymen. In nearly all the initiatives it was a question of distancing themselves from a museum and gallery world that had elevated cerebral, conceptual art to the highest good.

The ‘alternatives’ moved into vacant properties, sometimes squats, and set these up as a living, working, exhibition space. They did not limit their activities to the visual arts, on the contrary they wanted to allow space for all disciplines. The work process, doing it together and organizing it together were important.1 A few well-known Dutch examples are W139 and Aorta in Amsterdam and De Fabriek in Eindhoven. Exit Art, ABC No Rio and Artists Space could be put in this category in New York for example.

In Suriname in the early eighties the Waka Tjopu Kollektief was formed. René Tosari was one of the initiators. Because Waka Tjopu was founded at the same time as all sorts of other artist initiatives elsewhere in the world, this warrants the question of whether there are similarities. Also surely, since Tosari must have been familiar with the Dutch initiatives at least.

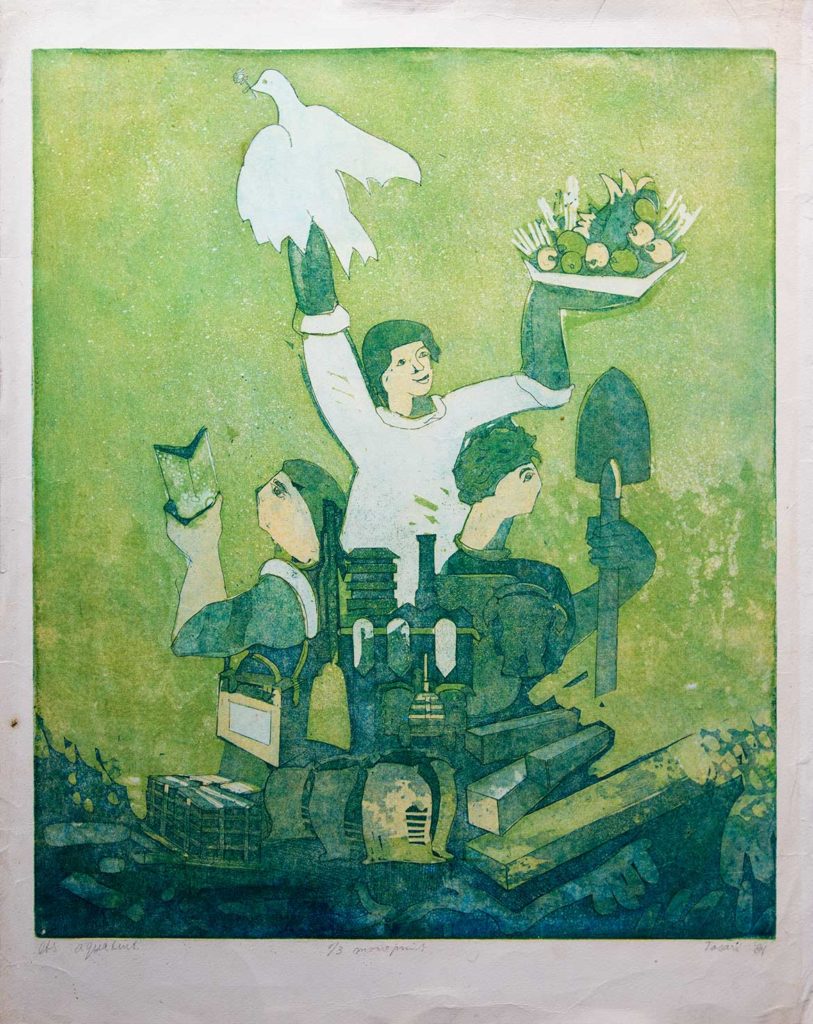

Untitled, 1984

The politics

The political upheaval in Suriname in 1980 – the military seized power – was ‘the starting point (…) of a social renewal movement’. The search was to find ways to concretize this. Artists were therefore among those who were brought in. Waka Tjopu filled this need. The aim was to use artistic education and to impart technical skills in order to strengthen the people’s consciousness, to increase their self-reliance and critical insight and in this way to implement social changes.2 Tosari preferred here to look for inspiration from educational experts such as the Brazilian Paulo Freire rather than fellow-artists from Western countries. He did not primarily see himself as an artist who makes autonomous work. He wanted to ‘lead the way in exploring the future. My person is not important, I want to give a message to the working Surinamese.’ 3 He even went so far as to not sign his work. ‘It is all about the product, not about me.’ 4

In effect protesting against the art world is a protest against society and therefore a call for social change, but at Waka Tjopu this call was directed at raising up the Surinamese people. Western artist initiatives were mainly aimed at regaining their freedom and improving their own work situation. This was a way to create better opportunities for their work.

The practice

The way they worked (together) did show similarities. Operating as an ideologically affiliated group was as relevant for Waka Tjopu as for many artist initiatives elsewhere. Solidarity and learning from each other were highly thought of. In each case the work process was often considered more important than the presentation of the outcome.

Waka Tjopu was not only engaged in art. All sorts of disciplines were given a chance, also in the composition of the group. There were artists, designers, graphic designers, photographers and even technicians (Tosari had been involved in street theater in the nineteen-seventies). On this basis both ‘parties’ can rediscover each other. An essential principle for many artist initiatives has always been that the boundaries between the disciplines must be broken down. Aorta held many concerts, installations were presented in New York discotheques such as Danceteria, performance art and theater became intertwined on the stage, the distinction between street art and high art was gone.

Another similarity is that most artist initiatives were short-lived.

Perhaps because the objective had been achieved. After a time the participating artists often want to completely focus on their own work again. René Tosari gave the following reason for his return to the Netherlands in 1990: ‘I wanted to take on new challenges in the visual arts. And what was also important for me at that time was my concern about my own production and about the experiments I really wanted to explore.’5

The context

In spite of similarities and differences, the time was evidently ripe for artist initiatives, otherwise they would not have become a global phenomenon in the eighties. They are inextricably linked to new developments in art, culture and society. Which probably explains why all kinds of artist initiatives cropped up again in upcoming districts of big cities and especially in African and Caribbean countries.

For many years graphic work had been an inseparable part of turbulent political movements. In the nineteenth century the Mexicans Manuel Manilla and in particular José Guadalupe Posada were already making flyers illustrating the news in order to make it accessible to the lower orders of society. They also used cartoonish prints to criticize the church and politicians. However they mostly gained their popularity through the illustrations they made for the Day of the Dead, celebrated as a national holiday in Mexico. Due to this popularity, in 1910 when the Mexican revolution happened people were grateful to use their preliminary work. Pamphlets and posters called the population to revolt.

One of the first actions of the Bolsheviks in 1917 was to take control of the printing presses. They were quickly used to print revolutionary posters that were pasted up in many locations to pass information to the people fast and directly. Heroic images – the clenched fist was one – in a style that seemed realistic, but which was mainly idealistic and thus biased. Through mass distribution the figures and symbols became iconic and they would lead to universal imitation.

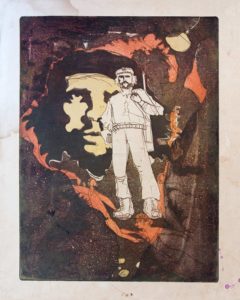

In early 1959 Fidel Castro deposed the dictator Baptista. The Cuban revolution opted for a state based on communist principles. The photogenic head of Che Guevara became the symbol of this doctrine. In other posters and pamphlets the visual language of the Russian revolution was obvious. Militant, heroic figures in uniform rising or fighting for their ideals.

The clenched fist and the freedom symbol came back again in the nineteen-sixties as a visualization of Mao’s Cultural Revolution in China, and also the democracy movements in cities such as Paris, Berkeley, London and Amsterdam. Atelier Populair in Paris, Poster Workshop in London and Rob Stolk in Amsterdam provided the graphic interpretation of left-wing ideas. Due to the speed at which they were produced the posters were often slapdash and text only. They were actually for internal use and did not need to inform the masses visually.

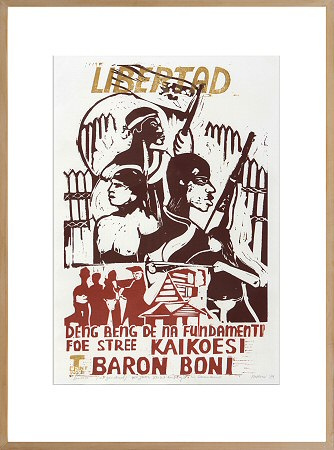

Given this long graphic tradition it is no surprise that when he returned to Suriname in 1982 and co-founded the Waka Tjopu artist collective, René Tosari used the medium of graphics to communicate his ideas on freedom. After all there was no lack of turbulence. In 1980 the military had taken control. They wanted to liberate the people, to make them aware of the value of their own culture and thus accelerate the process of decolonization. René Tosari placed himself at the disposal of this revolution.

400 jaar strijd in beeld, 1981

The influence

Although Tosari says that during his Waka Tjopu period he had little contact with other countries – ‘because of the language barrier, but chiefly because we were extremely busy’ – there are a number of reasons why his graphic work must have been subject to international influences.

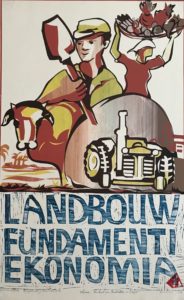

He studied at the Academy for Visual Arts in Rotterdam between 1970 and 1973. He majored in printmaking. During this time it would be impossible for him not to have encountered examples from the past. Given the mass distribution of the revolutionary posters these would certainly been part of his art history module (Che Guevara was on every student’s wall in the sixties. In Amsterdam often side-by-side with the Mao posters). Besides, a style comparison makes influences undeniable. The angular figuration in Suriname Voorwaarts from 1983 for example can be placed alongside posters from Cuba and Russia.

Sketch for Suriname Voorwaarts, 1983

Cuban Poster, undated

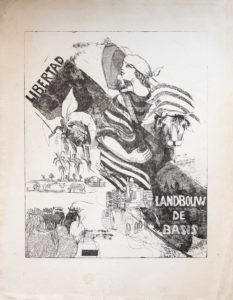

From the series Libertad it is the schematically represented figures, their standard military pose and the incorporated text that refer to earlier examples from other countries.

Untitled (400 Jaar Verzet en Strijd Suriname), 1981, linocut

However he is also different from his predecessors. He combines different printing techniques in his graphic works, he adds depth and layering. Tosari is conscious that he has to communicate a message, but this does not stop him from making room for detailing and originality. His predecessors were sometimes more limited in their technical options – the early Mexicans for instance –, but they were also often less professional and creative. The visual language of revolutionary printed matter was standardized to a large extent.

Che Guevara, 1982, etch/aquatint

Back in the Netherlands

Tosari has never totally abandoned printmaking, but after his Waka Tjopu period and his return to the Netherlands in 1990 the revolutionary graphic work largely disappears. One exception was the poster he made in 2004 to commemorate the February Strike. After 1990 painting features more strongly and his engagement adopts a different tone. The arrival of the internet and the rise of social media have moreover ensured that in general the classic poster and the classic flyer have for the most part lost their function. Calls via Facebook, Twitter etc. appear more effective both as to their reach and results.

In 2012 Tosari painted a remarkable self-portrait. He is standing in soft gray-white before a dark background. Right hand in front of his mouth, his glasses in the other. For the most part this background is a patchy dark green, but above his head, as if an extension is fanning out from his cap, it takes on the form of a forest landscape. The restraint in color is striking. Certainly because the little color he does use is reserved for the landscape, he has to go without color himself. The only explanation is that he wants to underline the importance of the landscape and concretize the mankind-nature relationship.

His love for the landscape seems to me to be something he has in common with many Caribbean artists. The critic Veerle Poupeye mentions the natural beauty of the Caribbean as one of the reasons for the popularity of scenery for artists. They are paying tribute to the beauty with an idealized representation of nature. Stereotyping fostered by pride. She even suggests that many artists deliberately capitalize on the taste of tourists with work like this.6 René Tosari has a different story. While he has indeed been influenced by the Amazon region in particular, this is where he gets his bright colors from; he actually uses this colorfulness to make the viewer aware of the dangers facing the Amazon region. It is being polluted and poisoned. By companies, but also by inhabitants and hired gold diggers. The colorfulness, ‘the samba in a color symphony’, will disappear if we are not careful. The primary aim of Tosari’s visual language is to generate this emotion. His view of nature then comes closer to the work of the Surinamese artist Rinaldo Klas (1954) than to that of his Caribbean colleagues. ‘Through my art’, says Klas, ‘I hope to convince my audience that we must treat nature with more respect.’8 Klas also uses the colorfulness of nature, but his depictions remain closer to reality. He does not use color to allot significance. Tosari’s visual language is moreover often more surrealistic and more enriched with symbols and (Javanese) references. The viewer has to work harder to discover his ‘message’.

Libertad. Landbouw de basis 1981

The Tosari style

In the course of the nineteen-nineties Tosari developed a recognizable painting style. Thus fully justifying his reasons for returning to the Netherlands. ‘He starts with oil paint and then at a later stage works this with acrylic thereby creating a patchy, lively texture.’9 In addition he applies another characteristic style principle. He outlines his figures – people or other natural forms – in white or black. This extracts them from reality. His canvas becomes a playing field with elements standing next to or opposite to each other, which often have no identifiable context, which have every freedom to play with reality, which enable references to mythical figures for example and at the same time may be referring to the present-day. They sometimes remind me of the collages by the African-American artist Romare Bearden (1911-1988). He also placed his distorted image elements side-by-side. Even the colorfulness is comparable. The outlining brings to mind the work of Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985). In his sculptures these are dominant, but he also uses this technique in his landscapes and cityscapes. In the nineteen-eighties it was a trademark of the now forgotten American artist Bobby G. As regards content his lines had almost no function, they were there to make his work recognizable as his.

The self-portrait that Tosari painted in 2012 fits into a series of works in which he completely abandons his familiar style. The works are about him, about memories of events from his childhood. It is as if he wants to translate this personal subject matter into a gentle, almost hesitant, vulnerable, realistic style, where the colors show their self-effacing side. Remarkably enough, a style that is similar to that of the Terug naar huis project from the eighties, a series of brown-greenish paintings focusing on the neglected plantations and which was the Waka Tjopu contribution to the São Paulo biennale. Is this series from 2012 heralding his return to Suriname? A decision, by the way, that can only have been emotional.

Even though he developed a recognizable style in the nineteen-nineties, he continues to occasionally return to a style of painting that is different. Just as he has never completely given up on his graphic work. He still has too much of a ‘soft spot’ for it. Which makes it difficult to compare him with other artists. In the nicest possible way: he is headstrong. Like every other artist he enjoys recognition, but he will never produce work that makes concessions to this willfulness or to his views on being an artist. This also explains why although his engagement took on a different form when he went to the Netherlands, more social than political, the political connotations never completely disappeared. Sometimes he uses a painting to directly respond to a political situation he does not like. A good example of this is a painting from 2007. A crudely depicted male figure rumbles through Surinamibo. The text Stop social political economical crime surrounds him. The World in Motion from 2012 visualizes the drama of the boat refugees through a man with binoculars. The man is looking at two overcrowded boats, the viewer sees what he sees and is thus forced to look too. These direct, emotional indictments are often in response to a newspaper article.

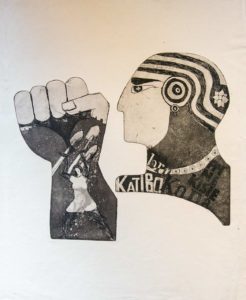

Katibo, 1982

The Bijlmermeer

Art appreciation was once a core objective of Waka Tjopu. He again became convinced of its necessity in the Bijlmermeer, a multicultural district of Amsterdam Zuidoost where Tosari worked for many years. In 1998 he joined Matchpoint Cultuureducatie Zuidoost, an organization that tries to develop self-confidence and self-awareness in primary and secondary school pupils ‘through letting them discover their cultural background, to identify with it and to be proud of it’.10 He was one of the artists who worked out and gave form to this principle. For him, this was not a job on the side to earn his living. ‘I consider it as a natural part of being an artist.’ He saw the work as stimulating when making his paintings. ‘I used the themes of my works to stimulate the children and I could not wait to start on new paintings inspired by the things the kids came up with. I inspire and am inspired.’ He did similar work for the Amsterdamse Stichting Kunstweb and De Blauwe Schuit in Hoorn, both centers for art education.

His enduring social engagement is also revealed in his involvement with the studio provisions for artists in Amsterdam Zuidoost. For example the Stichting Open Ateliers, of which he was a part, built twenty artists’ studios in the Kruitberg apartment building. They made sure that once a year they opened their doors to anyone interested. The idea was that artists do not only have to inspire each other and work together, direct contact with the public must also inspire them to carry on.

These educative and facilitating activities are similar to those in many African and Caribbean countries. Here, they are often set up and organized for the same reasons, but also because local amenities are sadly lacking. Art education, galleries, museums, studios may be taken for granted in Europe and the United States for example, but in many developing countries they are still a huge luxury. Potential or novice artists there often depend on the efforts of other, older artists. Suriname is itself an example of this. The Moengo-project from Marcel Pinas, where he tries in many different ways to address and develop the artistic qualities of the Maroons in order to thus preserve the Maroon culture from destruction, is not only comparable with René Tosari’s activities, I even think that Moengo was directly inspired by the Waka Tjopu Kollektief. Marcel Pinas, too, sees his so-called sidelines as an essential part of his work as an artist.

René Tosari is back in Suriname again. His work has changed. It has become more personal. Less stylized, maybe even less colorful. He allows himself to first and foremost develop and add depth to his own work. He has permission to freely indulge in his impulse for experimentation. This is not to say that his social and political engagement has disappeared. ‘They are still there, if more guarded. Or rather, to put it more clearly: I now work differently, but my heart tells me I am still the same person.’ The artist with a mission is still here. There is nothing I can or want to add to this.

Notes

1. Tineke Reijnders, ‘Kunstenaarsinitiatieven’. This text was published in Peter L. M. Giele, Verzamelde Werken, Amsterdam 2003;

2. Chandra van Binnendijk, Waka Tjopu. Kollektief van Beeldende Werkers. Het scheppen van een artistiek klimaat, Stichting Waka Tjopu, Suriname sa

3. Anonymous and undated newspaper article from the artist’s personal archives.

4. Idem.

5. Unless stated otherwise, all of Tosari’s quotes are from a written interview I had with him in September 2013.

6. Veerle Poupeye, Caribbean Art, London 1998, p. 143.

7. From an undated poem by Tosari from his personal archives.

8. From the introduction text about the work of Klas on the site of his gallery Readytex in Paramaribo.

9. From an article that I wrote in March 2007 for his exhibition at the SBK gallery in Breda.

10. From an introduction text on the site of Matchpoint Cultuureducatie Zuidoost. This text, by the way, could have been taken straight from the Waka Tjopu manifesto.

This article was first published in René Tosari. Diversity is Power, Jap Sam Books, 2018

.