So I think it’s very right for artists to engage in politics in their work just like they deal with other issues in their society, it’s still their mandate. At the end of the day, politics affects everyone, if there is a rise in sugar prices, I don’t know if artists don’t take tea or don’t use sugar. If there is insecurity in the country, the artists won’t even create, so we have to talk about these issues so that there is a change.

Matt Kayem interviews Ronald Odur

Art as a tool

Interview with Ronald Odur

Ronald Odur was the recipient of the Mukumbya-Musoke art prize, a locally based contemporary art prize, in December 2020. The bi-annual award was running for its second edition. Although still an emerging artist, his work has been shown and exhibited in various art exhibitions such as The Kampala Art Biennale(2018) curated by Simon Nami, The Last Image Show “The Silence” an international art exhibition in Tanzania and Lusaka Zambia. Odur mainly uses aluminium printing plates and copper wire. He seeks to tackle his ideas from different vantage points that may reveal themselves as sculpture, installation, drawing, and performance to vividly express the themes and narratives in the complexities of social-political interactions and their influence in the contemporary world. I hunted him down and got lucky to be invited at his humble abode next to the city center, a one-roomed house on the staff quarters of a primary school that he shares with his siblings. We talked about politics in art, dissected his practice and what the future holds for him in his pursuits. Odur is a laid-back soft spoken fellow that leaves most of the talking to his artwork that is often laborious and meticulous.

Odur explaining to me about his practice.

MK: You went to Kyambogo University and graduated with a degree in Interior Designing, how do you end up a contemporary artist instead of beautifying our living rooms?

RO: It was a diploma, there was no degree by then. I think being in spaces of contemporary artists and hanging out with the people in there especially 32° East Ugandan Arts Trust, has helped me to join this world. I remember the opening of the Design Hub, I met some artists and they told me that they don’t see me at 32 degrees because I just used to pass by. So at 32 is where I got introduced to conceptual art and then that’s when I thought of changing course to this ‘new’ art. Though it was difficult for me to understand, but with the help of people like Nikissi Serumaga(.. who explained to me more about contemporary art because my work was more of ‘NGO’ art by then, I used to work with a couple of them.

From the series, Worth Of Tax, Ronald Odur, 2020.

MK: I see human figures now, I have seen a Bible sculpture somewhere and I’m thinking, what are you generally interested in as an artist, what are your core concepts if you have any?

RO: I’m very much triggered by what’s happening in my immediate society and also what’s happening in the country and the world at large. For me, my work is very much rooted in expressing myself, what I see and what I feel, you won’t see a lot of consistence in what I put out, you will always get surprised. You will see me talk about religion, then politics and then the next day something social or personal. People look at me as an artist who airs out political views in my work. Yah they are right to categorize me like that because that’s what is eating up at our society right now. And that’s the only way I see fit to deal with these issues because I don’t see myself joining the protests on the street. The only street I have is my work where I riot or speak from though sometimes there are some pieces I create for my own consumption because I think they are very political and might cause me a little bit of problems. I don’t know if I can call that self-censorship but I do it at times.

No Hurry, Ronald Odur, 2019.

MK: Aluminium printing plates are your choice of medium, why is this material important to you?

RO: These printing plates have been in my life ever since I was a kid and there were important to me then because they used to generate for me some little money. So I grew up in a slum setting where at the end of it, you had these rich kids, the rich society if I may call it. Their kids had these nice toys that I admired and wanted to own. There was this hawker who came at the school gate selling toys that I couldn’t afford with the little pocket money my parents gave me. So I picked up the aluminum printing plates and sold them as scrap metal to dealers. I didn’t even know that they were printing plates. I was staying in Nsambya and when I passed by Nasser road, I picked up any kind of metal I saw. I later found out that the printing plate material was more valuable than the others as I was paid more than with steel or any other kind of scrap metal. When I grew up, I used to paint on canvas which was costly, I used old bed sheets sometimes and asked for paint from artist friends. I went on YouTube and saw this guy using Coca-Cola cans and I remembered the printing plates and started embossing them. From that day till now, I’m exploring this material in every way possible, I emboss it, create sculptural 3D objects from it.

MK: You started out working in two-dimensional relief sculpture but at the Silhouette Residency at Afriart gallery, we saw you move to three-dimensional sculpture, what prompted the shift?

RO: To be real, I had a talk with Daudi Karungi(director, Afriart gallery) who I showed one of my pieces and he then asked me, ‘what do you like doing as an artist?’. I told him I like crafting stuff. He went like, ‘you can craft something out of the printing plate’. I looked at artists like El-Anatsui, he crafted some bags out of printing plates. So I got ideas from seeing his bags. His were not even perfect and I thought I can make neater work. So my first piece was a shoe. From that shoe, everything else was easy to make. I believe in possibility and I think that with the printing plates, I can do anything.

MK: Yah, most definitely I can see that anything is possible with them, now that you are even painting on them. I couldn’t imagine that paint could stick on them. Please tell us about the paintings on the plates.

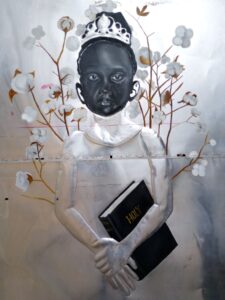

RO: So the paintings are part of a body of work I call the Pamba series. Pamba is Luganda for cotton.

MK: Congratulations on winning the Mukumbya-Musoke art prize. Your winning work, “Ebya Kayisali” takes on a Luganda title, what does it mean and how does it provide an entry into the work?

RO: I didn’t even expect it to win, haha. Ebya Kayisali means what belongs to Ceasar, from one of the Bible verses from Matthew, don’t remember the chapter. I had a series of works that lead to that particular work that won the prize. I called this collection, ‘The Worth Of Tax’ where by when they introduced the social media tax, 200 Uganda shillings was the worth of tax, the I thought about 50 shillings which is not in use right now though it’s still a legal tender. So I looked at the 100-shilling coin, then 200 which had some value because it pays some tax, which is the social media tax. I was interested in where taxation came from and whether its introduction ignited uprisings, what’s the motive behind the tax? I discovered they was a lot underlining behind the social media tax. There was the curtailing of freedoms, Bobi Wine saga and I saw this as a suffocating the youth majority population in Uganda. I remembered about reading about Mahatma Ghandi and how they protested because of a tax and then the Bible where tax was a problem. I thought about Ceasar as the person who introduced taxation and I picked up the phrase, ‘what belongs to Ceasar’. Should we give what belongs to Ceasar to him and then give what belongs to God to God.

Ebya Kayisali, Ronald Odur, 2020.

MK: Is this the first work where you directly tackled a socio-political issue?

RO: No this is not the first. I have created other works that tackle socio-political issues. That same work comes from a body of work. There is a piece I created about the censorship of art. There is a piece where I talked about the women in Iran facing challenges with their government, the Sharia law where they are not allowed to do some things. I made them kings in my work and they can do anything. It’s just a matter of realizing that they have the power in their hands. So I created this piece where the woman was covering herself but had a gun in her hands which represented power.

MK: Owing to the political situation in the country, where we’ve seen critics of the state getting arrested, locked up, tortured and killed, weren’t you scared to put out a work like that?

RO: Yah, I get scared but then I tell myself, this is my contribution, I cannot go to the streets, I would be taken in. For me, art remains the only outlet I can express my discontent to what’s happening around me. There are some works I just can’t put out or I use metaphors, abstractions so that it doesn’t directly get to be comprehended. I’m working on a piece I called “Classified” where I’m talking about the hidden budget that is issued to the military which they use to kill people and there is no accountability. Couple this with a lot of borrowing, both domestic and foreign that is pressing ordinary citizens. With such works, I take caution with how to put them out, I don’t think I will exhibit them in Uganda. One time my mum asked me why I was making what looks like bullets with which she added that I shouldn’t continue with it as she doesn’t want to lose me. I told her how I’m making an effort to hide the messages in the work in metaphors and abstraction.

She Is A King, Ronald Odur, 2020.

MK: I’ve had conversations with artists about lending their voices to the pressing political issues in the country, some think otherwise. I have however done some politically charged work myself. Do you think artists ought to deal with politics in their spaces through their work?

RO: Yah, it is a tool we have to use. You know art manifests in various forms, even music is a piece of art, then what are you going to talk about in your piece of art. Are you going to talk about nice things only? Butterflies? You want your work to leave a mark, create an impact, a positive impact, you don’t want your work to create a negative one. It is a calling, a responsibility for artists to express all these things in their work. So I think it’s very right for artists to engage in politics in their work just like they deal with other issues in their society, it’s still their mandate. At the end of the day, politics affects everyone, if there is a rise in sugar prices, I don’t know if artists don’t take tea or don’t use sugar. If there is insecurity in the country, the artists won’t even create, so we have to talk about these issues so that there is a change. It was art that changed the situation in South Africa, the music even under a lot of censorship. And going back to my work, Ebya Kayisali, I also got some inspiration from South Africa where they used to scratch out some songs on the vinyl records. So you listen to this nice music but when it comes to a Lucky Dube, it has been tampered with. So if it wasn’t for the music, maybe South Africa wouldn’t be where it is now. During slavery, the negro-spirituals… I think art is a strong tool that can change our societies.

MK: Who are the artists that have shaped your practice both local and international?

RO: Wow, this is a tough one, hehe. But my first inspiration was the late Benon Lutaaya who I had conversations with. There is a piece I created which was my first conceptual piece and I asked him how he used the papers to create what he created. I felt there was a connection to what he did and what I was doing and he told me to keep experimenting. So we had talks with him and there was a way he changed my thinking and the way I approach my practice. It’s not about creating something beautiful, it has to have meaning, a story behind. The British photographer, Othello De’Souza-Hartley is also a good friend who has advised and commented on my work on several occasions. I’m also influenced by the works of Ai Weiwei because he deals with socio-political issues like myself.

Ani Mutukulivu(Who’s holy) Ronald Odur, 2020.

MK: What future projects should we expect to see from you?

RO: I’m just looking at a solo exhibition which I don’t know when it will happen. I was looking at showing only installations in the solo but then maybe I will do that in the future, not soon. Of recent, I have been working on a series of paintings and installation pieces from my Pamba(cotton) series where I’m looking at how colonialism has infiltrated our way of understanding. For example, there is one piece called Egumba, I remember way back in school when you spoke your local language and the punishment was to wear this bone necklace. I spent five years in the Kabaka’s palace and I learnt a lot about the Kiganda culture. In my dormitory at school, I was the only northerner and I was stereotyped about my people eating birds which terrified and upset me a lot. But the day I accepted and owned it is when I understood that they just wanted to agitate me. That made me want to learn and understand my origins, I didn’t know that within my people, we had a chief. I learnt about our clan system and where I belonged as much as I soaked in the Kiganda culture. For me, in this body of work, I don’t want to talk about things that are not close to me like racism which I haven’t experienced.