Roy Ferdinand

First published: October 2018

About:

Welcome to New Orleans, a carnivalesque city of the highest highs and the darkest lows. Home to Mardi Gras and the birthplace of jazz, in the past decade the city has made a remarkable recovery from the near-death experience of Hurricane Katrina, yet still struggles with large issues—gun violence and crime, income inequality, drugs and the war on drugs.

For fifteen years, artist Roy Ferdinand (1959-2004) chronicled the street life and characters from some of New Orleans’s toughest wards. He created an epic body of work—some two thousand drawings scattered among private collections, galleries, and museums across the country—documenting the distinct, creative, yet often troubled culture of the city’s African American neighborhoods.

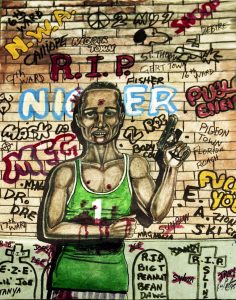

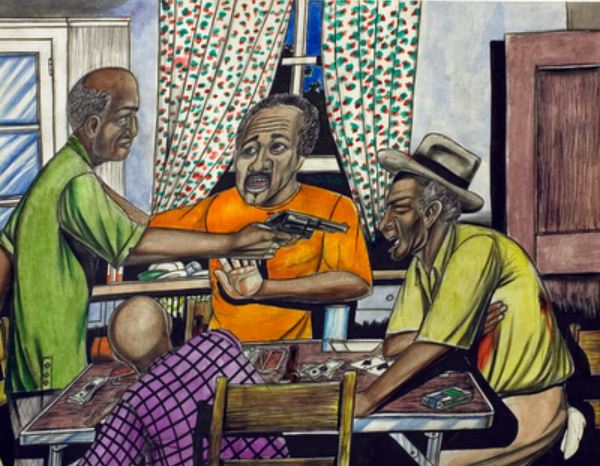

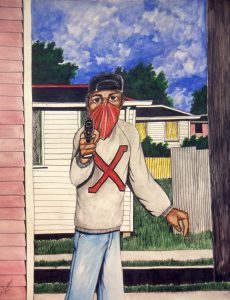

Ferdinand, who died at age forty-five in 2004, was a self-taught artist who called his work “urban realism.” His career coincided with the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s and 90s, an era when for many years New Orleans had the highest murder rate in the nation. His uncompromising vision often mixed social criticism with the exaggerated, self-aggrandizing style of rap, and a decade after his death his work remains powerfully relevant.

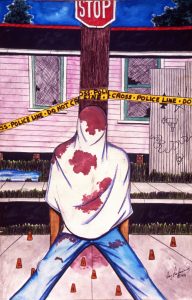

Drawn on poster board with drug store art materials—ink markers, colored pencils, and children’s water colors—his best works offer compositionally sophisticated, realist portraits of life in New Orleans’ impoverished black neighborhoods. Ferdinand compared himself to a battlefield sketch artist and drew on events he saw firsthand, heard about, or read in the pages of the local newspaper. “That’s real,” he said, when asked about one of his depictions of a drive-by shooting. “When drive-bys were common around here, for a long time the preferred way of killing someone, the weapon of choice, was a Uzi.”

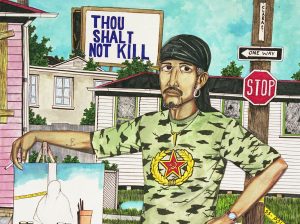

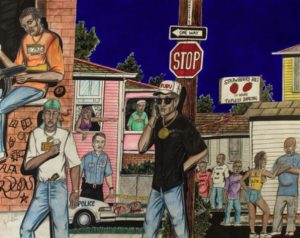

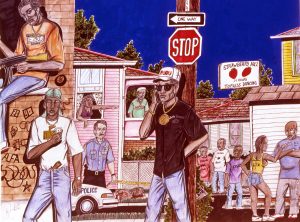

While often stark, Ferdinand’s drawings are also marked by irony, metaphor, and a sometimes startling humor. Street signs are a favorite detail—in many pieces STOP, ONE WAY and DEAD END stand behind young men wearing gang colors and holding weapons. Graffiti is a recurrent motif, with walls and fences covered in the signs and symbols of a violent underworld. “A name crossed out with an ‘X’ shows someone killed by a rival gang, a name inside a tombstone is a tribute to a gang member or a friend,” he explained to an interviewer. “A lot of times I use people I’ve known who’ve died on the street.” Telephone poles are another symbol. “They bring to mind the cross and the crucifixion,” he explained.

Ferdinand balanced his crime scenes with neighborhood portraits. These drawings, such as a “Popeye the Skateboard King,” worked as emotional outlets. “Popeye was a kid who lived in my mom’s old neighborhood,” he explained. “The expression he’s got here is saying this isn’t exactly how he expected his life to turn out.”

His skills as a draftsman and knowledge of New Orleans charge the atmosphere of his drawings. Beauty and menace somehow both show through in his azure skies, jumbles of sub-tropical vegetation, makeshift fences, and odd-angled buildings with broken windows and boarded doors. While he had a natural gift for revealing emotion and character with a few pencil strokes, his formal skills are often imperfect. Yet his misrepresentations—tilted buildings, bodies slightly out of proportion, multiple vanishing points—powerfully evoke a subject—New Orleans—that in his own experience was innately skewed and often morally off center.

In a series of self-portraits, Ferdinand shows him as, conversely, a Western gunslinger in a New Orleans ghetto and an artist-revolutionary critiquing the street culture around him. Had he lived to see Hurricane Katrina, he would have undoubtedly become one of the tragedy’s most perceptive chroniclers. His huge body of work stands as a singular vision of New Orleans before the storm, and a chronicle of social issues that still wait for answers.(text and images website artist)