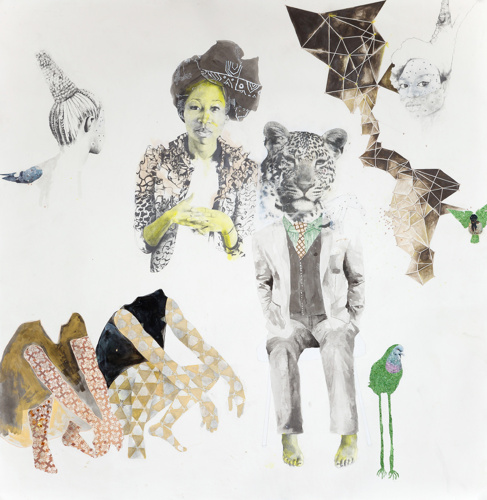

Standing in the cold, we met ourselves, 2014.

Interview with Ruby Onyinyechi Amanze

On the occasion of ‘Mutations’ at Tiwani Contemporary, London.

Published in ‘This is Tomorrow. Contemporary Art Magazine’.

Yvette Greslé

Yvette Greslé talked to Ruby Onyinyechi Amanze about her drawing practice before the opening of the group show ‘Mutations’ at Tiwani Contemporary. Nigerian born Amanze was brought up in Britain and received her fine art training in the United States. She is currently based in Brooklyn, New York City, where she has a studio. In 2006 she graduated with a Masters of Fine Art from the Cranbrook Academy of Art (Michigan). Amanze was a Fulbright Scholar Recipient in Art at the University of Nigeria in 2012/13. Mutations at Tiwani Contemporary closes 5 July 2014.

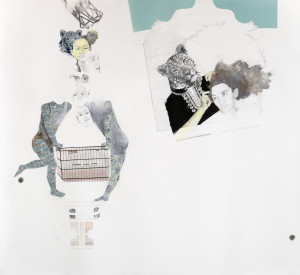

The garden palace and the folly of innocence, 2014.

The garden palace and the folly of innocence, 2014.

Yvette Greslé: Drawing is central to your practice. You speak about its vulnerability and its humanness. What happens in that space-time between yourself and the surface you are about to fill?

Ruby Onyinyechi Amanze: When you say the word surface I think about my background in textiles and working with fabrics. I see these materials as very similar to paper. I also think about surfaces as skins. Instead of putting something on top of a surface you can put something inside of it. You can dye fibres. You can draw and erase, and re-draw and accumulate an image that seeps into the surface. You can’t ever fully erase a mark. If you spill ink it seeps into the fibre. If you erase you’ve erased off particles of the paper. When I say the word vulnerability I’m connecting it to humanness. The idea that the evidence of the hand is so present; including mistakes and failure. I could spill ink intentionally. I could also in the process of being human spill something or make a mark that perhaps I didn’t fully intend. Then I have to have a conversation with it now that it’s there. The ink might decide to do something and the graphite might be laid on too thickly. All of these different elements are participating in the making of the drawing.

(….)

YG: Your work focuses a lot on place and displacement. The words you use to describe your drawings –alien or ghost – imply a kind of trauma. In historical work the idea of haunting and ghosts is associated with traumatic historical events. You have developed an alter ego called Ada the Alien. You explore the idea of aliens and galaxies; perhaps the politics of Afro-futurism?

RA: I was born in Nigeria, grew up in the UK and then moved to the US. In my formative years I had to figure out for myself what my identity was. I wasn’t fitting into any one category. This can cause a sense of disconnect; the feeling of not belonging anywhere. A lot of my work came out of a search for home. I looked at architecture and was interested in floor plans; spaces that delineated boundaries. Now, partly from having recently spent time in Nigeria, I am embracing a middle space. I’m recognising that it’s not my story: It’s a universal story. The idea of boundaries and having a set identity that is clear cut is dissolving. I embrace being an alien. Hybrid is a place. It is a culture and an identity. This gives me a sense of belonging.

Ogbonno soup is sweeter since we met, 2014.

Ogbonno soup is sweeter since we met, 2014.

The first character I developed was Ada the Alien. I was thinking about navigating space but also about wanting to have a space between myself and the story. I hear the word Afro-futurism when people look at my work. I guess there are some elements to it that are Afro-futurist: to do with fantastical elements and galaxies that I imagine. Other characters began to emerge after Ada, such as Audre the Leopard and Pidgen. ‘Kindred’ (at Tiwani) introduces the characters as a family. I thought of them as a family unit: a way to think about how they interact with each other or with worlds. It can be a galaxy world which comes up a lot in my work. Ada the alien has a visual likeness to me but her skin is always a fluorescent yellow. This started from a very basic reference to an idea of an alien. Originally drawings of her referenced several traditional Nigerian and West African hairstyles which taken out of time or place might be considered alien. Pidgin wears the green sparkly suit. Pidgin represents a bird that is free to move: I was thinking about migration and little freedoms such as flying. In Nigeria, which has about 300 languages, the Creole language is Pidgin. For the most part you can move around Nigeria and speak some version of Pidgin: people will understand you even though your mother tongue dialect could be completely different. I like the idea of empowering the hybrid. The ghosts are drawn from people that I know; identified as being part of some hybrid culture. The ghosts don’t always have a positive connotation but they are free to move even though invisible.

YG: Your drawings explore the idea of empty space.

RA: In a lot of the work now there is no reference to a specific place or time. None of the characters will ever be grounded on the paper. I might reference places and memories to do with Nigeria: a particular type of road marking; or the windows of my grandfather’s house. But I want there to be a feeling of nowhere or everywhere: the sense that these characters float in-between spaces and time.

YG: What drawing mediums do you use?

RA: I use traditional drawing materials such as pen, ink, and different kinds of pencils. I also do photo-transfers. I’ve been using some glitter but mostly everything is drawn with pencil or pens except for the photo-transfers. I also use fluorescent markers and metallic pigments. There are recurring aesthetics in my drawing. One of these is to do with erasure, and its presence as part of process: being able to remove marks and allow for that space where there are still traces of something underneath. There is a certain lightness to working with materials such as pencil and ink on paper. There is an ephemeral quality to drawing. Paper is going to disintegrate. It’s not a solid thing that has to be densely packed. You can crumple it and it can blow off in the wind. I like for there to be that connection with the materials I use which are very ephemeral and not fixed.

Published on 13 June 2014 (abridged version)

Yvette Greslé submits also interviews/articles to www.africanah.org.