“Absence, in the making of the photographs, seemed like a metaphor for presence, a way to affirm the continued relevance of the girls. By standing in place of portraits of the missing girls, the still life pictures of their possessions carry the same power of recognition that portraits would have carried.”

Emmanuel Iduma on the representation of the schoolgirls kidnapped by Boko Haram.

An Imagination of Terror

[i]

Sometimes time

guised as an arbiter of

things to come

dazzles you with premonition

Somewhere in a logbook of deaths

you find your name written

at first in unsteady lettering

but soon a sure one

Do not fight this

Even unnamable deaths

share this fate

– in ledgers of justice

all entries are equal.

[ii]

With great anxiety I wrote

an essay about mass deaths

Remembering gravestones

I’d seen in Sarajevo

also in Ijebu-Ode

crumbling beside sidewalks

emptied of visitors

As if in the years

between those burials

& my travels

an unquestioned doctrine

about human immortality

had gained young followers.

The poems I wrote following the massacre of hundreds of Nigerians in Baga, reproduced above, have served as placeholders for my thinking about distance—a distance that is first spatial, but also psychic. Nigeria, a country of almost 170 million people, with a land area of 923,768 sq. km. was amalgamated from two British protectorates in 1914. Although this amalgamation purportedly created a “Nigerian” identity, many Nigerians today continue to think in divisive ways. The terrifying operation of terrorists has, in the last five years, remained a northern Nigeria problem. Boko Haram, in the south, where the terror is a headline away, seems, at best, an allusive term, or a synonym for a comfortably distant evil, so that in a conversation my aunt might say, jokingly, “If you mess up I will Boko Haram you.”

I’m terrified about distances because they result in gaps, and these gaps are ideally the breakdown of empathy. It’s a similar gap between the colonizer and the colonized, for instance, that exists between the terrified northerners and the unaffected southerners. The empathy I propose cannot be based on physical space, but on an imaginative space. An empathetic response isn’t simply reported; it takes more time than a news cycle allows. Slow and deliberate, empathetic responses try to assert that each bone in a mass grave once belonged to a body and a name. They take newspaper accounts and imbue them with greater worth, telling stories ordinarily glossed over, offering through literature and photography what might seem like prayers and incantations for the dead and disappeared.

The distinction between an epitaph and an epigraph can serve to illustrate how distances can be bridged. An epitaph, in a sense, is what is inscribed on a gravestone, at the end of a life. An epigraph however, inscribed at the beginning of a book, is something written upon, at, on the occasion of, in addition—but is also a closing upon in space or time. Could epigraphs replace epitaphs? Could I, together with other writers and artists, offer epigraphs that point towards a beginning, a new lease of life, for the dead and the terrified? Our writing will be based on the knowledge that such epigraphs will be empathetic, closing upon the imaginative gaps between northern and southern Nigeria.

—

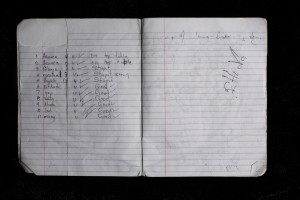

In February 2015, the month I write this, the schoolgirls kidnapped by terrorists in Chibok have been missing for almost 300 days. The only evidence of their continued existence, at least photographically, has been a screenshot from a video released by Boko Haram the month after the kidnaps, where dozens of girls are draped in dark hijabs, and purportedly reciting the Quran. But it seems hard to tell, while looking at the screenshot, that these are the girls kidnapped from a predominantly Christian town; girls who had worn threadbare uniforms, transcribed love letters in their composition notebooks, drew hearts on the first pages of their notebooks, and captured the attention of their male peers in florally patterned dresses. In essence, the photographic evidence of their existence in the hands of terrorists mismatches that of their life before they were kidnapped, as Glenna Gordon’s series shows. The mismatch is not merely the distinction between the dresses they wear in Boko Haram’s video and the dresses they had worn earlier; the anonymity of the faces in the screenshot does not seem to match the names on the objects in Gordon’s photographs.

It is fascinating that, absent in body, the girls in Gordon’s photographs remain poignantly present in spirit. The names on the covers of the notebooks and the captions of each photograph notwithstanding, their identities are portrayed with a certainty of their existence, as though the evidence has become indisputable. But in a certain way, the photographs also prove the disappearance of the girls, because clothes and shoes are lifeless, even disembodied, without their wearers.

The entire goal of this series, one might say, is to counteract despicability with hope. At the time the photographs appeared, there were claims by certain highly influential and ignoble Nigerians that the girls hadn’t, in fact, been kidnapped, and the “Bring Back our Girls” campaign was fraudulent at its core. Hence, the photographs became proof that bodies had actually been lost. What this suggests is that the evidential work of photographs does not consist simply in the depiction of an actual event, or face. It sometimes pushes beyond that to investigate how a less visible reality works, how absence can be brought to light.

Bringing absence to light, as Gordon suggests when interviewed by Teju Cole, is “like moving a mountain.” The idea to photograph the belongings of the girls was simple, but the realization was not. She was up against the immense power of the objects, the ghostly presences of the girls, and the sheer weight of their disappearance. “Each item,” she said in that interview, “had the distinct smell of the owner, faintly or strongly but recognizably.” Absence, in the making of the photographs, seemed like a metaphor for presence, a way to affirm the continued relevance of the girls. By standing in place of portraits of the missing girls, the still life pictures of their possessions carry the same power of recognition that portraits would have carried. After the photographs appeared in The New York Times, people told Gordon that her photos had helped them see the girls for the very first time.

—

—

The narrator in W. G. Sebald’s The Emigrants says,

“Looking at the gashed bodies, and at the witness of the execution, doubled up by grief like snapped reeds, I gradually understood that, beyond a certain point, pain blots out the one thing that is essential to its being experienced – consciousness – and so perhaps extinguishes itself…”

How does one carry within himself the knowledge of desecrated bodies, of truncated existences, and of horrors too gruesome for the eyes? I read that, after the massacre in Baga, a certain man said, “It is too dangerous to go and count let alone bury the dead.” This man, fleeing for his life, might have wished that the tragedy he saw would extinguish itself, so he would lose the consciousness required to experience pain.

I am not that man. I have only witnessed the Boko Haram menace vicariously, learning by pictures, word of mouth, and reportage the violation of human bodies. What I have is a consciousness. My consciousness is based on the knowledge that I do not wish for a life as cruel as one the man has experienced. From this consciousness comes a response, a resort to an unfettered imagination, so that like Glenna Gordon, who hauled a suitcase full of possessions belonging to the missing schoolgirls, I can depict, through my writing, the weight of grief and the burden of joylessness.

Copyright photos: Glenna Gordon

Photos are out of the series ‘Abducted Nigerian School Girls’.