Having an increased number of females working in the contemporary art scene is great. For the curators particularly, they have really played a key role in encouraging and promoting female artists.

A statement of the Ugandan artist Sheila Nakitende in conversation with Claire Nalukenge

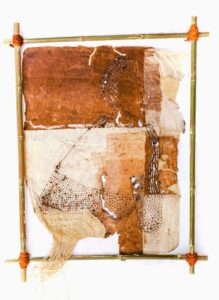

Cost of Oxygen, 2022, 111.5cm-x-91.5cm- Bark cloth paper raffia. Photograph by-Martin Kharumwa. Image courtesy of Borderlands Art

Claire Nalukenge In Conversation with Ugandan artist Sheila Nakitende.

The process of harvesting bark cloth as opposed to felling the tree resonates with the tree’s regenerative nature, which relates to us “Abaana Ba Kintu”. We are continually restored through embodying new physical and spiritual patterns from interactions amidst shared spaces. Our lives are interwoven just like fibres.

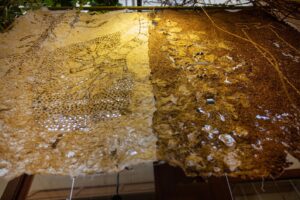

ABAANA Ba KINTU Exhibition at the Makerere University Chemistry Laboratory 2022. Photograph by Martin Kharumwa. Image courtesy of Borderlands Art

In this conversation, Claire Nalukenge learns from Sheila Nakitende about her sculptural installation at Makerere university and her general artistic practice. The conversation focuses on Nakitende’s installation titled “Abaana Ba Kintu”. This installation explores ideas of materiality, history, evolution, and environmental consciousness.

Claire Nalukenge (CN): Could you please unpack the title of the installation, “Abaana Ba Kintu” in relation to the exhibition?

Sheila Nakitende (SN): The title “Abaana Ba Kintu” was derived from the Luganda proverb Abaana ba Kintu tebaligwaawo translated “The Descendants of Kintu (the legendary ancestor of the Baganda) will not die out”. I was investigating the continuity of descendants of Kintu through our evolutionary behaviour. Having researched and explored material culture with focus on natural fibres, I was drawn to transforming bark cloth not only because of its versatility but the regenerative nature of the mutuba tree from which it is harvested. The process of harvesting bark cloth as opposed to felling the tree resonates with the tree’s regenerative nature, which relates to us “Abaana Ba Kintu”. We are continually restored through embodying new physical and spiritual patterns from interactions amidst shared spaces. Our lives are interwoven just like fibres. I used the bark cloth transformation as a material language to address the evolution and establish multiple conversations about our lives.

The artist in her studio. Photograph by Martin Kharumwa, Image courtesy of Boderlands Art.

CN: The entire installation appears handcrafted and encompasses a combination of natural fibres. What was the purpose behind engaging with natural fibres?

SN: My interest in working with natural fibres has been on going. I started out as a painter. Then later started experimenting with different media especially wastepaper. After my solo exhibition “40 Twists” in 2013, a revelation to switch to working with natural fibres happened when I realised that most paper was made from fibres. I started researching on natural fibres in my community, what and how we were using them more so for art making. I applied for a residency at the Women Studio Workshop New York in 2017 to further my research with focus on bark cloth alongside other fibres like raffia and abaca for paper making and there in a sustainable art practice. That was the birth of what you witnessed in the installation.

CN: You exhibited your work in the Makerere University chemistry laboratory. How do you relate your work to the context of the exhibition space?

SN: When I delved deeper into material transformation, I noticed that the process was not only an arts practice, but also science based. I have a vision on extending the language and knowledge of what I have been discovering. I realised I needed to engage with the science community as key part of my audience for this purpose. I was motivated further to establish a relationship between this art (traditional technology) and modern scientific space. The collective decision was then made to have exhibition at the Makerere University Chemistry laboratory.

Lockdown I 2020, 50cm-x-67cm. Bark cloth paper raffia. Photograph by Martin-Kharumwa. Image Courtesy of Borderlands Art/Duo Maama W’Abaana II, 2022. 58cm-x 140cm man 72.5cm-x-123cm woman-girl. Bark cloth paper raffia. Photograph by Martin Kharumwa. Image courtesy of Borderlands Art

CN: When you talk about changing environment, did you only stop at engaging with the chemistry laboratory or students engaged too in making bark cloth paper?

SN: The students have not engaged in making bark cloth paper. However, a relationship was established which was one of the goals. The arts and science community gathered in one place and so many conversations happened. Look at it like a woman who is in the kitchen, she sets a fire and places the pot on the fire, it will start boiling.

CN: Speaking about the biodegradability of bark cloth, don’t you think that if the bark cloth is mixed with synthetic chemicals, it will lose its biodegradability component?

SN: I am not using synthetic chemicals. Everything in my process is natural from the binders to formation aid and hopefully with natural dyes. The intention also is to use natural resources but with a mind-set that when we use, we replace. You know when something is not considered of value to society, it is most likely destroyed. But when we understand the values and trail of our material production, then we can still nurture its sustainability. Therefore, to answer your question in simple terms, my process is not harmful to the environment.

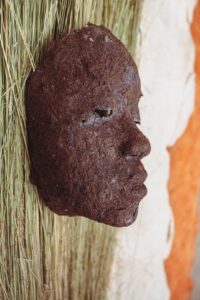

Muddugavu Mask. Edition I, 2022. Photograph by Martin Kharumwa. Image courtesy of Borderlands Art

CN: The way you are talking about bark cloth shows it has persisted globally and within a Ugandan context resisting colonialism snares and kingdom abolition. And yet, some pastors like Robert Kayanja still associate bark cloth as demonic. What is your view on this perception in relation to the resistance of this cloth?

SN: All of us have found these things on earth but that lies in how these things have been used. Sex was given to mankind but how has it been used? It’s like the medicine sold in pharmacies, some people misuse it beyond the prescribed dose. Bark cloth was given to mankind and how has it been used? That is basically it, how do you use what you have been given? So, the reason why pastors have bias towards the bark cloth lies in what they have witnessed. If a pastor found me using bark cloth the way that I do, I do not think they would have a problem with it.

CN: Your artwork more effectively and constructively projects tales of environmental preservation within and outside a Ugandan context. What role do you think you’ve played in bringing this significant subject beyond national borders as one of Uganda’s contemporary artists?

SN: I think I have triggered a certain degree of mindfulness and inspiration not only among the creatives but people in other spheres of practice. I feel the role is in obviously the material culture investigative process and delivery of the artwork. It was not only commentary but interactive and transformative. The use of natural materials accessible to us, the transformation and conversation on issues that were not alien to us all in a space that was most likely presumed inaccessible for that kind of engagement.

CN: You, the curator, Helga Rainer, and Nantume Violet were the brains behind this exhibition. Why do you suppose women were the brains behind this exhibition and what is the significance of this geared women involvement in relation to the current contemporary art scene?

SN: It just happened, and it worked out. Everyone has a calling, but I will say I am forever proud of us. Not often will you see women supporting each other but these ladies believed in what I was doing. The significance in relation to the current contemporary scene is that now the food will get tastier. I feel there is no self-pity and all, it’s a matter of identifying what you can do and identifying like-minded people. There were some men on board too by the way, and the team functioned very well.

The artist in her studio shredding bark cloth, 2020.-Photograph by Timothy Gambu. Image courtesy of the artist

CN: With reference to Violet Nantume and Martha Kazungu, how do you relate this female engage with the increased number of female curators working on the contemporary scene more so within a Ugandan context?

SN: Having an increased number of females working in the contemporary art scene is great. For the curators particularly, they have really played a key role in encouraging and promoting female artists. For example, my practice is not directly commercial, but Helga Rainer and Violet Nantume saw that it was something they could engage with and journey with me. Their brilliant efforts manifested a successful project. In a Ugandan context, I am certain we will create an environment that encourages fellow practitioners to excel.

CN: Fred Mutebi also makes bark cloth paper; do you see a future collaboration venture?

SN: If you study my background, my practice has been very collaborative. If our visions towards the future are aligned, why not?

CN: What are your concluding remarks regarding this exhibition in terms of its meaning on materiality, history and how you intend to push? Is there another exhibition on the way?

SN: In terms of materiality, the exhibition is just the beginning. It was an introduction into my current practice on material culture specialty and transformation. There were very many layers to it that could not be unfolded at once. The evolution is a revolution, on its way to so many experiences. History is being made, recorded and new breeds are coming to town.