“I discovered that I come from a family of practitioners, of healers, something that in the family…a Christian family, was silenced actually. It was never spoken about, even till today,” he reveals.

Athi Mongezeleli Joja in conversation with Sikhumbuzo Makhandula

ART REFLECTS THE TIMES

A conversation with with Sikhumbuzo Makhandula

“Colonial Grahamstown was a frontier town. It still is…” once wrote the late art critic Colin Richards.

It’s a lazy Wednesday afternoon. There’s no presence of bayonets or militias, but grand testimonies of conquest everywhere, even in the relentless guitarist occupying strategic corners, “begging” for alms. Mind you, he’s not meek but demanding. Listen to his songs!

“Art reflects the times,” the sermon from artist Sikhumbuzo Makhandula begins on a very high-pitch. Like in his performances, Makhandula assumes a different him. Not just because he transforms and transgresses in the performative act, but also because difference marks him apart. “It is a necessity. And with the way I work, I needed to address certain things using art. When it comes to performance, when it comes to photography – I wanted to reflect the times. How I see things and how they affect me. Not to speak back necessarily but to say something.” What this hidden gap between back chatting and insisting on being heard? Njabulo Ndebele referring to Sol Plaatjie once described this as “tactical humility which is consciously undercut by the confident poise of language and style, and whose expressed reservations about its own merits asserts the very opposite of inadequacy.”

Makhandula studied in Cape Town, first as a fine art student at Ruth Prowse School of Art, and then quitting to train as an interior designer at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT). Reflecting on how he ended up, as it were, back to the beginning with fine art, Makhandula says it wasn’t just a mechanical move or something that indexes indecision. He credits this itinerancy to his curiosities in issues of space and in architecture. However upon realizing the work regime in the design industry, its constrictive and client-orientated routines, he was left displeased. Returning to study Fine Art, currently at Rhodes University in Grahamstown where he is doing his final year, he says, “I had not yet found my voice in fine art and I felt there was a need for me to go back. A necessity actually! And now that I am back, things are actually much clearer. Like how to address certain things that I want to address which in interior design I would never be able to.”

Makhandula connects this movement with a fugitivity of his life more generally. “I was always displaced as a kid,” he says. He didn’t grow up in one place. He was born in the small town of De Aar, Northern Cape, and moved between places like Cape Town. Though born De Aar, his parents were not from there – they trace their origins elsewhere, in the Eastern Cape. This is the eloquent picture of South African history, as a story of displacement and homelessness. It then makes more apparent the incessant fixation with questions of place and belonging in his vocabulary, which spills over to his work.

“This has intensified my interests in geography and movement,” he says reflecting on his decision to move to Grahamstown in 2012, after stints in Johannesburg and Cape Town. “In 2008” he relishes, “it became apparent that I had a calling. And the calling that I had needed me to trace back my lineage, basically.” It was from his mother’s side, a religious family of Anglican faith, long detached from such practices.

But, beneath the veil of staunch religiosity, and amongst ruffles of things left unsaid, some traces linger. “I discovered that I come from a family of practitioners, of healers, something that in the family…a Christian family, was silenced actually. It was never spoken about, even till today,” he reveals. This double-consciousness is pervasive in Makhundula’s work with spiritual sensibility but in such ways that it distinguishes itself quite tidily from the theatrical turn to shamanism, slowly formalized as an aesthetic referent in much of contemporary South African art.

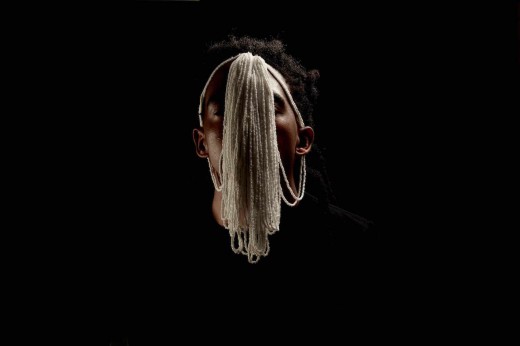

Always dressed in his clerical red attire, bearing a whip on one side, and “traditional” objects on the other, Makhandula’s work straddles a complex network of historical references, more so the unabated violence of the colonial church and its role in dispossession. At certain point his work inhabits this space of cultural confluence, raising embarrassing questions. “For example how do you even begin to think of the church as innocent while the entire thing actually is build on top of our people’s bones? At every point of our digging, we discover these bones … prosperity built on top of our bones.” His face tenses, but so does mine.

“By the time I decided to move here, it was already clear intobana the whole thing of how much the church has impacted on the traditional and also the entire African belief system. This is something which then in my work…umh…my work actually became an outlet to partly digest and navigate this discovery and journey that I am on… some of the contention that I have with the institution that is the church, more so here in the Eastern Cape because we are in Grahamstown, and that history became quite apparent that one needs to address that. But also reconcile certain things actually.”

Here reconciliation isn’t tantamount to compromise or acceptance of colonial evils, as we have come to know. It unashamedly points us to the impurities of our own backgrounds. But most especially, on the role of early African independent churches for example and how they reinterpreted Christianity for emancipatory purposes. And more specifically, as Steve Biko would say, for the resilience of a battered culture. For Makhandula this murky space needs to be narrativised rather than occluded: “The work became an outlet to be able to negotiate these two,” he says. At moments, especially his performance work tends to force us to contemplate of his creative output as always slipping out of the thick veils of the artistic enclosures into life. But also at its crudest, to unsettle the breeding contentment about such things as home, culture and freedom, when nothing has changed.

The work finds its beauty, as Makhandula insists, when the “norm is disturbed. Beauty must disturb!” This is what Richards somewhere calls, “a sometimes inelegant beauty, a beauty of distractions, diversions, delays.” We barely spend a minute on the formal aspects of his work; we slither back, as if we have parted from it, into the cave of history and ethics, talking around the work. Mind you, not in such ways that things, as perceived, come from the outside in, but rather what is perceptibly thought of as coming outside is already inside. And music is such a trespassing insider, keeping time – out of tune. “I think music is very integral to the whole journey actually. A lot of the time it becomes an anchor. Currently I am immersed in the music of Johnny Dyani. Thinking about the content he’s talking about … the music carries you.”

With imposing erudition and clarity of mind, he thus says: “My work is deeply situated in politics… it’s very political.” Here he means the political in its ethico-political configuration of the social. “It needs to! For me to be able to address the current times… now…for me to make sense of where I am… I need to look back. So the more I look back, the more it becomes apparent that politics have been more integral actually in the way I think, in the way one is brought up and in the way one is sensitized to space. The church, actually… the institution… I always come back to the church… its through its acculturations, dispossession and the impact… and the violence to the body. Like, I live in Grahamstown and I am subjected to the façade of the cathedral on the daily basis. And it’s also because, one is spatially positioned in relation to this architectural buildings – what it means to the body, and its regulation, and also psychologically. So it becomes apparent that one needs to address this in the work unapologetically.”

This kind of vocabulary has gotten a grip and flavored the mood of contemporary South African consciousness – from prominent to more discrete spaces, which have previously been the domains of ignorance. For Makhandula, art must “speak back” to the ethical demands of its time. Perhaps this time to speak back by saying something. “It has become important now actually, to speak back in a very political way. And address it, also not apologetically because most of the time, you become…sort of… sensible, in dealing with these issues.” There comes a time when one must adopt the insensible ways of dealing with our times, doing what Johnny Dyani might call “a fowl run.” I guess one can end with a note that Sikhumbuzo Makhandula’s work isn’t simply a reflection of time here and now or time left behind, but also time discounted of its temporality. It is a struggle to reflect back a deflected defect of modernity – the unintelligible story of blackness and the screaming wounds in its flesh.