Given his unease with institutional rhetoric, and charming disinterest in ‘integrating into the circuits of contemporary art’; Dokolo intentionally operates from the edge. From where he wishes to be ‘uncomfortable’ and somewhat ill-at-ease with what is intended for the collection every time it is broken up for exhibition. In order, as he describes it, everything is challenged; the artworks, the collection, and their collective interests. Because for Dokolo “if it’s not painful, if it doesn’t hurt then we are not doing something right.”

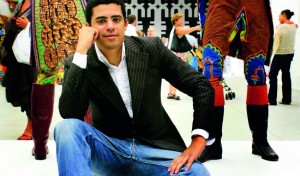

Rajesh Punj on the collector of contemporary African art Sindika Dokolo

Sindika Dokolo interview

Trigger Happy

As an orator and ambassador for contemporary African art, Sindika Dokolo eases into the role with such accomplished ease, that his ability to win you over is second only to the strength of the works in his collection. Eloquent in three languages, and tirelessly ambitious for the future of what he holds in his hands; Dokolo describes his intentions for the artworks he has as being very different from other blue-chip collectors. Geared by his own determination to re-write African history, he sees the collection as a vehicle for cultivating cultural upheaval. As he says “I like the fact that we don’t institutionalise ourselves. We don’t see ourselves as an important institution, because somehow we lose some freshness, and sharpness (if we were to do that). I like us to always to be at the limit, at the edge, and outside of our comfort zone.” Championing left wing politics, ‘Africanity’, American Andy Warhol, and the ebullience of Angolan’s the world over; Dokolo draws on essential elements that prove him right. And when given to discussing aesthetics as he sees it, it becomes utterly apparent that in the right hands, art is much more than an attractive prop. For Dokolo it acts as an impossibly impressive dialogue device for encouraging swathes of people who may not otherwise register the sensation of seeing their first Kendell Geers or Yinka Shonibare, of the value of art as the spirit of an age.

Nick Cave, Soundsuit: # 11.018, 2007, photo James Prinz, courtesy artist and Jack Shainman Gallery New York

Impressively self-assured Dokolo recalls how his acquiring German Hans Bogatzke’s entire collection of over five hundred works of contemporary African art in 2005 at the age of just thirty-three, put him among a handful of Africa’s leading collectors; just as it altered entirely his perspective on his own societal and generational significance. For Dokolo the newly acquired collection proved to be his gilded cup, as he impressed upon audiences his determination to integrate Africanity into the international arts scene. Securing the collection “has been an amazing adventure because it has allowed me to meet a lot of incredible people; and it has given me an interesting opportunity as a young African, (who has always lived in the shadow of previous generations), to actually fight for something noble. For a real cause that was more than for our own interests.”

And with a swell of interest for the candour and creativity coming out of Africa at the time heightened by less favourable images of corrupt politicians and civil war, Dokolo was subsequently invited to engage with the art world. Unfortunately such niceties were misshapen in 2007, when he and his curatorial colleagues were invited to contribute a proposal for Africa’s inaugural pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Leading to their being awarded the pavilion over France and Austria; only to then have proceedings unceremoniously high-jacked by institutional politics.

With Venice’s 2007 biennale under his belt, and as a signal of his intent, in 2010 for the inaugural Trienal De Luanda, Dokolo intentionally chose not to house any of his works in a museum style setting. Deciding instead to impress upon an unassuming audience the strength of contemporary art, by propositioning works as public commodity.

Wangechi Mutu, You Love Me, You Love Me Not (detail), 2007, photo Ines d’Orey, courtesy the artist and Foundation Sindika Dokolo.

Given his unease with institutional rhetoric, and charming disinterest in ‘integrating into the circuits of contemporary art’; Dokolo intentionally operates from the edge. From where he wishes to be ‘uncomfortable’ and somewhat ill-at-ease with what is intended for the collection every time it is broken up for exhibition. In order, as he describes it, everything is challenged; the artworks, the collection, and their collective interests. Because for Dokolo “if it’s not painful, if it doesn’t hurt then we are not doing something right.” Which proved the basis for his initiating a quite remarkable baptism for his collection, as he explains so decisively when drawing attention to the alchemy of the artwork; “what we did was to put artworks everywhere in the city for four nights, or five nights, during the Trienal De Luanda. So there were two hundred, maybe three hundred outdoor artworks. So for all of the young artists, (for the duration of the Trienal), these works belonged to them.” At its most poignant Dokolo advocates that art, like religion before it, is at the centre of a person’s wellbeing.

Interview

Rajesh Punj: Incredibly interesting to hear you speak about the collection, and especially the point you made about the French artist and his claim of one of the works from your collection, being entirely anecdotal. Which you appear to argue against, by asserting that African art has greater content to it; ‘beyond aesthetics’, ‘beyond the decorative’. Which is something I wished for you to initially discuss in more detail.

Sindika Dokolo: Well there is always this question about African art and for me the notion of ‘African art’ doesn’t make much sense. Defining art by its continent of origin, demonstrating its diversity; isn’t really meaningful for me. There are a lot of collections that try to put some sense into it; for instance the (Jean) Pigozzi collection will say ‘well its only black people, and I am looking for people who have not been exposed to the world of art’. Which creates its own moral problems. So I have tried to come around to solving this issue by saying first that it is an ‘African collection of art’, which is an African point of view on the world of art. And secondly what I am interested in is Africanity. So it is not the nationality of the artist (that interests me). So if you look for instance at what we have done, in 2007 the guy that opened the (Venice) pavilion with me was Miquel Barcelò, the great Spanish artist. There was a piece by Andy Warhol, and there were pieces Jean Michel Basquiat. And the point that I was trying to make was that I resent the concept of ‘African art’. It is an unintelligent concept to me. Art is a universal form of expression; it doesn’t make any sense to start to make these kinds of categories.

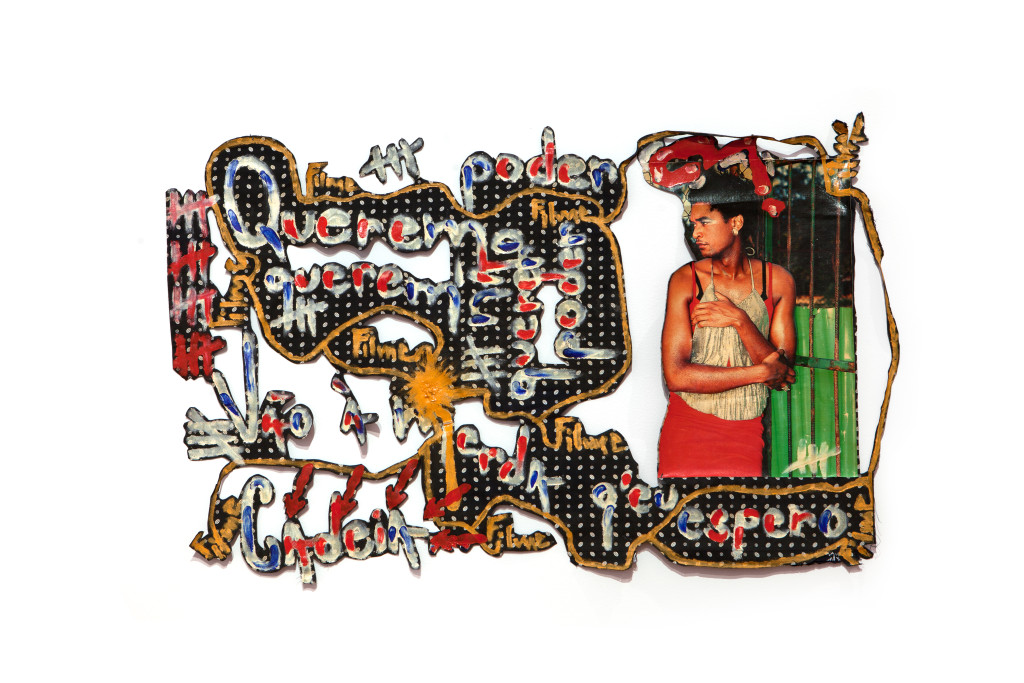

Nástio Mosquito, Mulher Fósforo, 2006, photo Ines d’Orey, courtesy the artsi and the Foundation Sindika Dokolo.

RP: So how do you explain contemporary shows like ‘Pangaea’, at London’s Saatchi Gallery, that is defined entirely by geography?

SD: Well the final objective is marketing, so you need to be able to create some kind of a buzz on the market, and create the feeling that something is hot; so you can capitalise on it. I mean I am not selling anything so for me as a collector the collection needs to make sense. Because when we acquired the Hans Bogatzke collection, overnight we became a cultural point of reference. We had a critical mass, and we were all of a sudden confronted with questions that we couldn’t ignore. The fact that there is still a lot of exorcism prevailing as far as Africa is concerned; as far as Africa’s contribution to the history of art, and to the world of art. Aswell its integration into the circuits of art. The moral responsibility of not saying that Africans survive on one dollar a day. And there is something about (the collection). Because culture and art are exactly the fields where things should be happening in Africa, and are currently not happening. So as Africans, and as a collector, and as chairman of the foundation, this is where I found a relevance. It is by actually addressing all of these issues. Putting a finger on exactly where it hurts in order to create some aware of all of these questions.

At the same time it has been an amazing adventure because it has allowed me to meet a lot of incredible people; and it has given me an interesting opportunity as a young African, (who has always lived in the shadow of previous generations, who were our father and forefathers before us; and all of whom fought for independence and against racism); to actually fight for something noble. For a real cause that was more than for our own interests. And this has been my opportunity to open some doors in order for sons and daughters and their kids not to have to do so. And it becomes interesting from that perspective.

RP: It appears you take on a responsibility of nurturing the emerging artists that you have works by, whilst developing your collection at the same time. Do you feel a duty to provocate a better future for your collection’s subcultures?

SD: The problem in our case is that most of the countries in Africa are bankrupt. So basically all our governments are trying to manage their own bankruptcies, and everything becomes a priority. So you have a million priorities before art and culture.

RP: With that in mind what is the future for the arts in Africa? And on a more fundamental level, what of art schools and art institutions? How do such centres of learning exist in countries where the economics add up to electricity and water over art and culture?

SD: The thing is (art) is considered an accessory so you could perfectly live without it. So because you can live without it it’s not important. But it has to do with the loss of ideology. To me an African government should really pay a lot of importance to the ministry of culture. But the ministry of culture should be ‘culture’, ‘youth’, ‘sports’ all put together, and put up as a minister of state, or something very special. Because it requires us to pursue excellence in those fields that has nothing to do with any particular political party, but that encourages a consensus. And this is where you work on the person, and on the citizen. This is where you reflect on your values, and you build society from the inside out. And unfortunately it is something that we have lose. In the case of Angola there was a left wing government and associated ideologies until the late eighties. It is interesting to look at that particular history because during the war there were absolutely no means available for anything, but culture thrived. The ideology at the time worked on the principle that any base of a system is the people themselves. So everything that could work to politicise the person; to make the person stronger and more responsible worked to enhance culture. And morally engaged in the social and political process. All of which made a lot of sense and was a priority.

So during these difficult times we had an amazing generation of classical ballet dancers in Angola. We have previously been champions of roller skate hockey, ever seen there was a championship. And we have been eleven or twelve times basketball and swimming champions.

Thameur Mejri, I love my god, my gun and my government, 2012, photo Ines d’Orey, courtesy the artist and the Foundation Sidika Dokolo.

We have artists of the generation of Fernando (Alvim), and all of this (the collection), came out of his imagination. All of this is of his making. And my fear of our going toward a capitalist system is that we lost all ideology and all sense of priority as far as culture as a political tool to engage with the individual in society is concerned. Unfortunately we became a much more materialist society. And I realise that because I come from another generation, and I have this understanding of how significant it is to work on the person. To engage with the person, and to confront the audience, the public, and society; with its own short-comings and limits. To take people out of their comfort zones, so that they can reflect upon their own values; and of what values our society carries. Such dialogue and reflection can only be done in the field of art and culture. And because I am conscious of that, that creates a responsibility and I have to do something about it. It isn’t something the government is going to do, it is something that I am going to have to trigger myself. If I don’t do it, nobody is going to do it, and I am going to have to do it in an efficient way. So this is what turned this whole thing of the collection into something more than about aesthetics or an individual ego. As any kind of investment or whatever; it is really as political as it gets.