Africanah.org at 5: We celebrate the 5th anniversary of this magazine with the re-publication of a number of remarkable essays or interviews. The last article in this series is on Sokari Douglas Camp, written by Allison Young, first published May 8, 2016.

While the Nigerian-born artist has become renowned for her sculptural adaptations of traditional Kalabari masks, and for her pointed critiques of Western museological displays of African visual culture objects, this exhibition shows the artist, instead, in dialogue with the history of Western art.

Allison Young on the Nigerian artist Sokari Douglas Camp

Blind Love and Grace, 2015.

The Poetics of Nature, the Politics of Junk

Sokari Douglas Camp at the October Gallery

Sokari Douglas Camp, Europe supported by Africa and America 2015.

Sokari Douglas Camp’s welded-steel sculpture, Europe Supported by Africa and America, 2015 borrows its composition from a William Blake engraving of the same name. Both works feature a triad of female figures—allegorical representations of the three titular continents—who are joined in an intimate embrace. Africa, at left, clasps the hand of Europe, at center, while extending her left arm around the small of Europe’s back in a gentle, supportive position. Europe is also cradled by America, at right, who reaches her left arm across her neighbor’s shoulders.

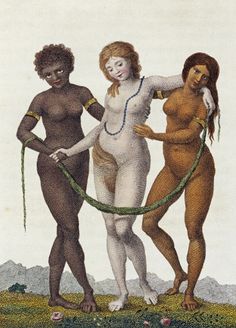

William Blake, Europe Supported by Africa and America, 1796.

Blake’s original engraving was produced in the late eighteenth century as part of a suite of illustrations for J.G. Stedman’s Narrative of a Five Years Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, a book that petitioned against the violent treatment of slaves in Dutch colonies. The image allegorizes the economic entanglement of the three continents while also drawing focus to the subjugation of Africa and America, who wear gold cuffs on their arms to represent their enslavement. A vine-like sash—thought by some scholars to connote tobacco leaves or other New World harvests—hangs across and in front of the grouping, dipping at the center in such a way that it mirrors the arc formed by the girls’ own arms, which continuously wrap around one another, closing the loop. They are, by implication, captive together, inextricably bound by the exploitation of land and bodies wrought on by European imperialism and the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Three Graces, 2015.

In her own version, Douglas Camp updates this scenario for the modern age and with new subjectivities in mind. A closer look at her tremendous steel goddesses, who are styled in the contemporary fashions of each named region, reveals their somewhat mournful expressions; the seductive, searching eyes of Blake’s America and Africa are here downcast and heavy-lidded. There are several important differences between these figures and those rendered by Blake (the most obvious being the bestowal of clothing on the three allegorical women), but one of the most significant is her addition of petroleum hoses that dangle from each end of the braided vine in the women’s hands. Oil is at the heart of so many of our contemporary conflicts and civil wars, and the extraction of fossil fuels from the earth is causing irreparable damage to our ecological system at an unfathomable pace. As in Blake’s time, Douglas Camp seems to suggest, violence today is still related to the consumption and control of natural resources, and wars are waged in service of the West’s incorrigible culture of mass consumerism.

Botticelli, Primavera, between 1477 and 1482.

This piece is one of several new works on view in Douglas Camp’s latest exhibition, Primavera at London’s October Gallery. While the Nigerian-born artist has become renowned for her sculptural adaptations of traditional Kalabari masks, and for her pointed critiques of Western museological displays of African visual culture objects, this exhibition shows the artist, instead, in dialogue with the history of Western art. Titled after a seminal painting by the Italian Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli, who remixed Graeco-Roman mythology with the dominant artistic and ideological expressions of Catholicism, this exhibition features anachronisms, cross-cultural references and astute social criticisms.

Primavera, 2015.

Primavera, 2015 (detail)

Despite the traditional associations of the season of spring with harvests and natural bounty, many of Douglas Camp’s latest works invoke the more unsavory consequences of overconsumption, reflecting a world that is ravaged by both excess and paucity. The eponymous work of the exhibition is Primavera, 2015, an impressive, life-sized figural sculpture whose form is extracted from Botticelli’s own painting of this name. In the original, one of the artist’s most enigmatic compositions, Venus is flanked on one side by the three graces, draped in translucent Classical gowns, and on the other by a scene depicting the nymph Chloris chased by Zephyr, the god of Wind; Chloris launches forward, but turns her head to face her captor, a pose that allows Botticelli to masterfully render her windswept hair and gown. To her left stands the nymph’s subsequent incarnation as Flora, the goddess of flowers; she appears calm and regal, clothed in a floral gown as she scatters blossoms across the fertile ground beneath her.

Douglas Camp’s Primavera, constructed in steel and detailed in gold leaf and acrylic paint, depicts a Nigerian woman in the guise of Flora, distributing flowers as she dynamically lunges forward, her bare feet surrounded by brightly colored petals. The piece is technically exquisite; Douglas Camp has managed to imbue the industrial material with a sense of weightless motion, fashioning cut-out patterns across Flora’s metallic gown. This West African Flora seems confident and alert. Yet, upon a closer inspection, the viewer will find small toy cars dispersed within her bouquet of flowers, in the floral crown that wraps around her headdress, and across her dress; it as if the wild, blooming landscape that Flora represents has been invaded by a sprawling junkyard.

Posing With a Gun, 2015

Prick Gun, 2016

Just as Blake sought to illustrate the consequences of Western greed—the inhumanity of Europe’s exploitation of colonized and enslaved peoples—Douglas Camp’s sculptures reveal the dark side of contemporary materialism. Several of her works depict figures wielding firearms, such as Posing With a Gun, 2015, and Prick Gun, 2016, both constructed in nickel-plated steel. In the latter, the soldier’s own limbs seem to merge with the rifles he bears; he raises one arm triumphantly towards the sky. As Gerard Houghton notes in the exhibition’s catalogue, many of these smaller works make reference to ongoing violence in Nigeria, such as the terrorist carnage wrought by Boko Haram or the increasingly militarized state police.(1) As an American, I was also moved to reflect on the disturbing rise of public shootings in the U.S., where police violence towards black victims has also become disturbingly commonplace.

These themes place Douglas Camp’s work in dialogue with other recent projects by contemporary African artists. The Mozambiquan artist Gonçalo Mabunda’s sculptural assemblages, for instance, are forged from dispossessed AK-47s, shell casings and military wreckage; in the form of chiefly thrones, they speak to the relationships between political and military power, as well as the global distribution of arms. On the other hand, Douglas Camp’s careful attention to the poetics and politics of cloth mirror Godfried Donkor’s and Yinka Shonibare MBE’s own investigations on the relationships between cloth and expressions of identity, power and global commerce.

Some of the most interesting comparisons can be found across London. Primavera is one of several current exhibitions here that pay homage to Botticelli’s oeuvre, the most prominent being the Victoria and Albert Museum’s exhibition Botticelli Reimagined, which showcases five hundred years of art both attributed to, and inspired by, the eponymous artist.(2) The V&A’s exhibition is presented in an anti-chronological order; it opens with the most contemporary works before leading viewers through the nineteenth century and ultimately Botticelli’s own time. It is striking how many contemporary artists have associated the painter’s works with popular culture and twentieth-century consumerism; Alain Jacquet’s Camouflage Botticelli (Birth of Venus), 1963-64, capitalizes on a visual pun that links Venus’ birth atop a seashell to the international oil corporation (Shell); as in Douglas Camp’s own work, Jacquet’s painting features a gas pump slung around the goddess’ arm.

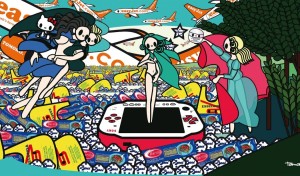

Tomoko Nago, Boticelli. The Birth of Venus.

Tomoko Nagao’s superflat rendition of the same painting assimilates corporate logos into the mythical scene. Venus’ divine sea is here polluted by EasyJet airplanes and Barilla and Bac packaging.

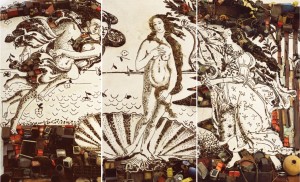

Vik Muniz, The Birth of Venus

These homages to commodity culture are contrasted, at the V&A, by references to excess and domestic waste, as in Vik Muniz’ photograph, The Birth of Venus, after Botticelli (Pictures of Junk), 2008. That image features a birds-eye view of Botticelli’s painting constructed entirely from materials scavenged by local catadores from Jardim Gramacho, the country’s largest landfill. Muniz’ Pictures of Garbage series draws attention to the close proximity of poverty and environmental damage.

Douglas Camp’s exhibition grows more complex in dialogue with these projects. When approached through the lens of new materialisms and ecological theory, her works can speak to the agency of objects; firearms, petroleum and discarded automobile parts can all be seen as Latourian actants that are contributing to environmental crisis, civil wars and the widening gap between extreme wealth and destitute poverty.(3) Perhaps the sheer beauty of her works (and Botticelli’s) is a ruse. It is not so easy to escape complicity, no matter how much one condemns political violence; every iPhone owner, this writer included, holds in their hands a sample of the precious metal coltan, mined in central Africa by impoverished workers, some of them children, under deplorable and dangerous conditions. As long as we sustain this dependency, this materialist status quo—which Jane Bennett writes “requires buying ever-increasing numbers of products purchased in ever-shorter cycles”(4) we bind ourselves to the reality of exploitation. While the sculptures on view in Primavera, by and large, do not contain found objects (with the exception of toy cars), they seem nonetheless to chronicle the ongoing conflicts related to mass consumption, intercultural violence and the strain we place on the natural world.

Lovers Whispering, 2016.

Red Grace, 2016.

Douglas Camp had initially sought to explore themes around beauty and love, as Houghton notes, in order to find solace after making a series of works about the Ebola crisis in West Africa. To be sure, there are stories of beauty, love and fertility in the exhibition—as in Lovers Whispering, 2016 and Red Grace, 2016. Yet, “no sooner did Sokari begin thinking of rebirth and renewal, of flowers and Spring,” the critic writes, “than incongruous thoughts of sweets, new cars, materialism and the clash of cultures quickly joined in the ‘conversation’ stream she describes as filling her head while she works.”(5) As with most myths, the dark and the light coexist in close proximity. In the new sculptural suite on view in Primavera, then, perhaps this type of vital matter cycles back into the picture, entangled—just like Blake’s tobacco vine—in the humanitarian crises of our present age.