Her choice of materials regards decolonization. She exchanges brightly colored acrylic paint for natural earthy hues derived exclusively from organic products; with coffee being particularly important. She also uses turmeric, bluing, charcoal, bee wax, ‘pimba’, strips of black cotton, rusty nails, and wire. A new path in her artistic career that may have come from her speaking from an ayllu for historical, cultural, and symbolic significance.

Miguel E. Keerveld on the work of the Surinamese artist Sri Irodikromo

Tyekelan, 2021

SRI IRODIKROMO

Udan Liris re-imagines time

Udan Liris, Javanese for soft rain, refers to hope and is a batik pattern. With her solo-exhibition in Paramaribo, Sri Irodikromo focused on this spatiality. She delved deep into the history of cultural mobility and the culture of colonialism. As space of artistic explorations that narrated violent and resilient in the context of the European-Caribbean relation, Udan Liris re-imagined time and presented a “sense of place”. This event, a phenomenon resulting from a relationship between humans and places, is one of many sentient “places” (De la Cadena, 2015). Sri Irodikromo replaced her previous vivid paintings inspired by batik and in her new work I sensed the re-manifestation of an urge for social justice and ecological conversation against implications of imperialism. In the intersect of the political and the spiritual she entangled the process of batik and storytelling in her search for inclusion. The curator and colleague-artist Kurt Nahar involved guaranteed exciting nuances.

The past within the present

I find the past within the present while exploring Udan Liris and feel the Caribbean in this archive. The name Caribbean comes from the non-European words canibales or caribes. But words such as Cannibals and America are European inventions to create distinction and location and establish distance between Europe and the America: a connection based on an unequal transaction of political power. To understand how this inequality acts different in terms of spiritual power, I take Suriname for example. Even though this nation is isolated from the rest of the world, we know that we are global… We are global, because we are part of a complexity that merges a diversity of knowledges, of languages, of ethnicities, and of beliefs. As a quite inclusive space – different than the European and how their history narrates our region – the Caribbean has been racialized. On the other side, the European is self-racialized by its endless mobility and the tight security at the EU borders against anyone non-European, because “whiteness can only dissolve its multiple ethnicities by racializing everyone else” (Guevara, 2019). What to say about blackness as experience and celebration in flexibility of racialization?

‘Mitoni’ and ‘Rukun & Adat’

Weaving technology is worldwide very popular and in Irodikromo’s practice essential. My understanding of her work goes beyond customs and traditions passed on by her Javanese ancestors. She imagines de-construction of the European as the world’s center and as the reference of global history; a ripple effect in which Udan Liris re-connects the current environmental crisis, colonialism, racism, and capitalism. Some understanding of alakondre-fasi is required for this manifestation. Even though alakondre-fase is not translatable, alakondre can be understood as the opposite of apartheid and fasi is lingua our franca for method. In attempts to translate alakondre many refer to “universal” (Ensie, 2017) in the context of winti (Afro-philosophy in Suriname). However, Udan Liris is performed beyond the territories of the Afro-Surinamese and is rather a manifestation of the art-place correlation. This brings my understanding of alakondre to both a story and a history of “socio-natural collective” in the Caribbean.

I relate alakondre to what modern political theory articulates as “peasant consciousness”. I also think of alakondre as a network beyond the human world, imagined as global weaving: an awareness of globalization beyond social constructions such as human, race, gender, class, nation, and corporation. In Latin America this awareness state is known as ayllu relationality. Both ayllu and alakondre are ambiguous events transcending the possibilities of translation and the impossibilities of territories. Ayllu is an Andean-based relationship “defined as a group of humans and other-than-human persons related to each other by kinship ties, and collectively inhabiting a territory that they also possess.” To speak from the ayllu rather than for the ayllu makes any difference in terms of ‘representation’ of the collective. In a similar process, all the beings in the world – people, animals, mountains, plants, artworks etc. – are like threads because ayllu is as weaving (De la Cadena, 2015). To read Udan Liris like being-in-ayllu or alakondre, weaving is essential in contextualizing globalization.

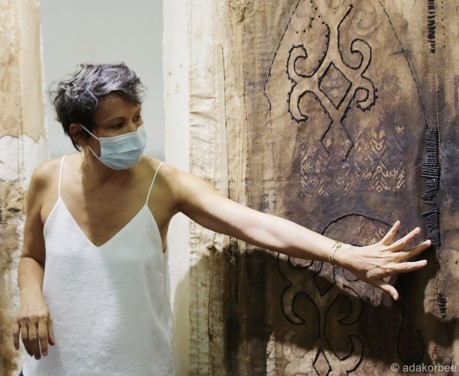

The artist did guided tours during her solo-exhibition ‘Udan Liris’

Being global

Can the Caribbean move freely through time and space? In conversation with Udan Liris, I challenge the idea of being global. To become global, mobility is essential as equal transaction. According to Francisco Guevara, “the idea of the world becoming more mobile is a masquerade for the differences in which we experience mobility” because the capacity to move implies the condition of freedom. Mobility is very specific and a social construction that gets distributed unevenly as a resource. “Why are we failing to achieve mobility on global scale, if it is an integral part of regular work-life for cultural professionals?” he asks. Kirsten Buick argues that “freedom cannot be granted; it can only be taken away”.

Since the Caribbean is a place shaped by imperialism and where freedom is usually experienced at the expense of identified targeted groups, mobility is a representation that carries several burdens, including how it is experienced and its effects (Guevara, 2019). How than, are we able to be global in the world? I think all nations are inherently connected with one another. Because Suriname is built by colonial history creates a fascinating narration in Irodikromo’s use of performative gestures, in which humans and other-than-human are together as beings. They are “composing the ayllu of which they are part and that is part of them” (De la Cadena, 2015). Based on exploration and oppression between nations, being-in-ayllu at globe scale remains a fantasy. But I understand Irodikroms’s hopeful narrative in Udan Liris as subject matter that aims to revert this type of coloniality.

Her choice of materials regards decolonization. She exchanges brightly colored acrylic paint for natural earthy hues derived exclusively from organic products; with coffee being particularly important. She also uses turmeric, bluing, charcoal, bee wax, ‘pimba’, strips of black cotton, rusty nails, and wire. A new path in her artistic career that may have come from her speaking from an ayllu for historical, cultural, and symbolic significance. Her way comes from a very personal depth and reveals an urgency to understand globalization. This almost inevitable development seems to fall over her gradually, gently, yet persistently and thoroughly, like Udan Liris… soft rain.

Installation ‘Rahasia’ and painting ‘Jaji’

Hopeful

I clearly see Sri Irodikromo depicts her heritage as hopeful. To embark Udan Liris, is to see that knowledge brought to Suriname from Java is present and simultaneously a re-manifestation of diversity, inclusion, and identification. Artworks such as Mitoni, Rukun & Adat, Tanah Sabrang, and Potrek demonstrate an urge to increasingly incorporate the culture of ancestors in the context of Suriname. Therefore, Irodikromo points to her titles as “words in Javanese that cannot be translated” because in pursuit of translation meaning get lost and “each word becomes a story” she knows. These titles are cultural aspects of the Javanese community in Suriname and refer to: a ritual performed at 7 months pregnancy, unity & knowledge of ancestors, shadow created by animal leather, and image/portrait.

Installation ‘Potrek’

In entering the exhibition, I am aware that this archive is beyond representations. The installation Potrek e.g., depicts ‘portraits’ of indentured laborers in Suriname based on organic material to re-encounter them as non-commoditization. Up on arrival, in 19th century Suriname, immigrants from Java had their portrait (as they pronounced it ‘potrek’) taken: “a process in which each held their formally registered number in front of them as their identification”, as Irodikromo explains. According to her “their names were considered far less important”; a reason why includes batik pattern as the ‘traditional’ clothing immigrants wore at arrival. To highlight the individuality of these portraits, some of the fourthly visual pieces installed here portray numbers. With childlike curiosity, I could image her understanding.

This is her way of being-in-ayllu. Udan Liris is is inspired by untold stories about Javanese immigration to Suriname; a narrative performed as ahistorical documentation. I think of Sri Irodikromo her identification as ambiguous, and this knowledge and intuition is extensive and urgent dialogue. Within the project ALAKONDRE: A Space in Time at Readytex Art Gallery, she deepens and researches her experience with identity; undoubtedly connecting with what theatre maker and art director Alida Neslo articulates as: “Suriname has been global, even before the word was sexy”. In the Caribbean complexity we are strongly convinced that our region is global. Have the rest of world become global as the ideology of globalism had promised?

Installation ‘Tyekelan’ and painting ‘Wayang Kulit’

Udan Liris archived an undocumented event on global scale. I can sense how events like these create a crucial space to discuss the “historical blind spot that constituted them”, not only because of a need for a global discourse about histories we will never grasp since they have been taken to the graves. These untold stories are now hidden in Sri’s visual pieces that triggers our imaginations, to challenge what Dipesh Chakrabarty calls “asymmetric ignorance”: modern ignorance that does not acknowledge the existence of spiritual leaderships.