Two artists, each effectively navigating the metamorphosizing artscape in Africa, meet for a tête-a-tête before the Investec Cape Town Art Fair 2020. Artist/art correspondent Zihan Kassam looks at the philosophy behind Stanislaw Trzebinski’s imaginative bronze sculptures and asks about his new life living in South Africa.

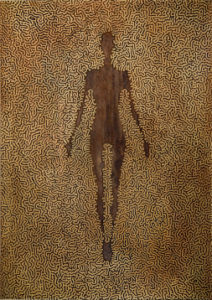

Chaotic Balance Woman, Etched Brass and Epoxy, 2018, Edition 3, 100 x 70 cm

Dans la tête: Stanislaw Trzebinski

A colony of sentient beings from the dim-lit underworld, Stanislaw Trzebinski’s bronze sea-sages possess a knowing more profound than ours, a compassion deeper.

Part stalagmite, stalactite or coral, Trzebinski’s sculptures are the unsolved beings of our cavernous green seas. They are noble spirits, the tangible shadows that reside in the rocky recesses of mottled waters. Powerful and pensive, they are retreating from the crestfallen souls of our secular world.

The imagination is inclined to drift this way at Stanislaw Trzebinski’s studio at The Woodstock Foundry in Cape Town. His creations all feel as if they were conceived far away from his new home. Born and raised in Kenya and inspired by years exploring the East African coast and bush, Trzebinski fuses the human form with elements of nature, playing with the boundaries between us and our environment.

Stalagmite Buste, Bronze, Edition 7, 2020, 91 x 32 x 24 cm

At his solo exhibition at the Southern Guild last year, Stanislaw Trzebinski exhibited three-dimensional artwork in the form of LED lighting fixtures, furniture and other functional forms made from patinated bronze, wood, stainless steel and epoxy resin. The gallery was transformed into a strange ecosphere, an alternative underworld In the Absence of Light. Flowing from one series to the next, the artwork at his latest solo exhibition, Pantheism, at the EBONY/CURATED Gallery in Cape Town (until May 2, 2020) dabbles with spirit and the belief that all living things are a manifestation of the divine.

Installation view, Ebony/Curated Gallery, 2020

Evoking strong emotional reactions from his swelling audience, Trzebinski’s artwork makes us question our behaviour and our purpose. Contemplating the strange metaphysical world, he creates, our primordial sensibilities are reignited.

Intertwined in Stanislaw Trzebinski’s narrative are the sentimental whispers of his childhood, a nostalgia for an ocean once thriving in its full glory, and chronicles of a parallel universe where everything is celestial and interconnected.

ZK: Stas, we met in Woodstock recently and had an interesting conversation about pantheism and also the relationship between man and nature. Since then I can’t help but wonder if the universe itself is conscious. Some of your latest bronze beings, part flora, part human, embody a sacredness, as if they are communing with the cosmos. Can you tell us a little about the character of your new bronze-cast statues?

ST: This body of works was an exploration of our complex relationship to the Earth over millennia. The works are a depiction of the human condition in a state where we were not removed from the natural world, but more so, part of it. More and more we find ourselves removed from nature. Modern society doesn’t value the natural world in the way that it deserves. As for the characters themselves, they are idols or totems that depict the balance we had with the natural world. This has been all but lost in the modern world. Sculpturally, I wanted the viewer to have a second look. Some of the pieces are figurative, while others are not. Upon closer inspection you see a figure, a face, a hand. This is intentional. I wanted the audience to question what was being imposed on what. Is it man on nature or nature on man?

The Chaos Theory, Study XI, Patinated Bronze, 2020, 18 x 34 x 4 cm

ZK: It was incredible to see your sculpture in the flesh. We spoke about your process, your textures and patinas, and the unique elastin you have concocted especially for your molds. I’m particularly drawn to the blue-green patina on bronze. I am also intrigued by the organic patterns, which are clearly inspired by ocean floor. You also photograph all your own work. Your work seems highly demanding compared to my painting for example. How do you organize your time, and would you say that you work differently to the more traditional approach to bronze casting?

ST: Studio life is always demanding, but in all the best ways. When I first decided I wanted to pursue bronze as my medium, I reversed the learning process. In 2012, I left the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, after only a year. I moved to Cape Town for six months to assist at a studio and bronze foundry. I learned the processes involved in creating bronze sculptures – the molding, the casting, and the limitations of these processes. I think that this knowledge allowed me to push the boundaries as to what is possible with bronze. I can foresee technical difficulties in the molding and casting ahead of time and avoid them.

Only after I learnt the process did I actually start learning how to sculpt figures – with a lot of trial and error – many failures and a few successes. A lot of the mediums that I work in are not the classic mediums that other sculptors work in. For instance, I never use water-based clay. I prefer wax and wax-based clay, which has a much longer shelf life and possesses qualities that allow you to be far more detailed than with conventional clay. Recently I’ve started using 3d printing and sculpting technology that has opened up the possibilities for me.

From a time-management perspective, the answer is simple: lists. That’s the only way to do it in my eyes. Deadlines help a lot – nothing like a pending deadline to help get things done!

Colony, bronze, 2019, 50 x 45 x 30 cm, photo: Stanislaw Trzebinski

ZK: Your studio is otherworldly. I am enchanted by the expressive poses and expressions of your colony of coral-people, if you will. Your showroom is exquisite, with gallerists and collectors coming through regularly. I envy the position you are in. Your work is receiving a lot of attention and from the perspective of a fellow artist, Cape Town is treating you very well. Work aside, can you share some of your insights about life in Cape Town and how it might compare to life in Kenya for example?

ST: Cape Town is an incredible platform for a young artist to get the necessary exposure that is vital at the beginning of your career. The art scene here is vibrant. There are monthly art events that take place like the First Thursdays for instance, where galleries in town stay open late and new exhibitions open. We have the Cape Town Art Fair which has become an international event, and this really helps put African art on a level playing field with the rest of the world. It really is the hub for art and design in Africa, in my eyes. Apart from that, there is just so much that one can get done here in such a short period of time – production wise. From my studio, it literally takes less than five minutes to get to all of my specialists and suppliers that I use for materials and producing things.

Kenya will always be my home I think – and what I miss most about it is my strong connection to the land and its people, my family, my close friends and of course the natural beauty of the country, which I have many fond memories of being exposed to as a child with my parents.

What Have We Done II, ST176, Patinated Solid Copper, 2020 30x31x30, version 2-1/Hide, Bronze, edition 1/7 + 1 AP, 2018, 81 x 25 x 20 cm

ZK: At the Investec Cape Town Art Fair 2020 (ICTAF), one of your four sculptures at the EBONY/CURATED booth in the Main Section, was a forlorn figure, part woman, part coral, cast in a seated position, hands holding knees, face hidden. The title is What Have We Done? Another captivating sculpture was Hide. What are they hiding from? Do the titles and sculptures address the environmental damage on our planet? Do they explore the psychological repercussions of our society’s growing list of political and social grievances?

ST: They were a depiction of the shame that many of us feel from knowing the negative effects we are having on the natural world just by being human. Almost everything we do, from buying groceries to cleaning our clothes and washing our hair, has damaging effects on the natural world. I’ve become hypersensitive to that, and so these pieces are “hiding” from the truth. Many of us know what’s going on but choose not to do anything about it. We turn a blind eye.

There’s also a sense of shame in the works. Almost that they don’t want to show their faces. But there is this juxtaposition because they are also covered in coral and so they are part of the natural world themselves which means they are only harming themselves in the process. It’s a vicious cycle.

ZK: When you were at school in New York, your spirit dwindled, and the environment did not suit you. I felt a similar vacuum in Canada and felt I needed to return to Kenya to flourish creatively. Do you think you returned to this side of the world because it is home or is it Kenya in particular that makes you tick? Will you share a little about your experience in the USA and the pull that this continent has on you?

Resonance, \Eetched Brass and Epoxy, VED, edition 1/3, 2020

ST: I think you are right. I really did feel like a fish out of water in New York, partly because as a child of Africa, the gritty city life did not do much to make me feel positive and inspired. In fact, it did the opposite. This coupled with the fact that I had spent two summers casting my first bronze works at a foundry in Cape Town. I had a taste of the good life and was deflated about having to stay in New York another three years. There is something about Africa and the people that keeps things interesting. Yes, we have third world problems, but I think those issues make Africa what it is. It is unpredictable and ever-changing. It keeps you on your toes. Ultimately, I missed being at home in nature. The sense of freedom that I had in Kenya didn’t exist in New York. In hindsight, my experience in New York led me to do what I do today. New York lacked something fundamental for me. People are not as conscious of nature, which is something that is engrained in me from living in Africa.

Installation view, Ebony/Curated Gallery, 2020

ZK: The Tomorrows/Today segment of the Investec Cape Town Art Fair 2020, curated by Nkulej Mabaso and Luigi Fassi, featured artwork by artists with a strong connection to the African continent. Exhibiting artwork by artists from across the globe, the curators did not seem preoccupied with static ideas of Africa or what African artists should look and be like. Africa could be a mere idea expressed by the artist. You couldn’t really tell that the art was ‘African’. What a relief that artists from Africa no longer have to look or act a certain way or create artwork with an ‘African-ness’. African artists are just artists making art. What changes regarding inclusion have you observed at the different art platforms in Kenya or South Africa?

ST: I think that in the globalized world we live in today, it is fair to say that African art has greatly evolved from the stereotypical forms in which many people used to categorize it in the past. Artists, as you say, make art in Africa. Many of them, like other artists from all over the world, are greatly influenced by the world around them. I think that African art is only just starting to get understood for what it is and I am excited that people with incredible stories are able to tell them through their art.