FROM THE ARCHIVE 1: February 2016:

Thuli Gamedze – a middle class Black person, as she calls herself – observes the art world in South Africa, specifically in Cape Town, in an attempt to reconcile personal encounters in various art spaces that seem to present multiple tensions between viewer, artist, art object, and gallery structure- due to the latter’s implied neutrality.

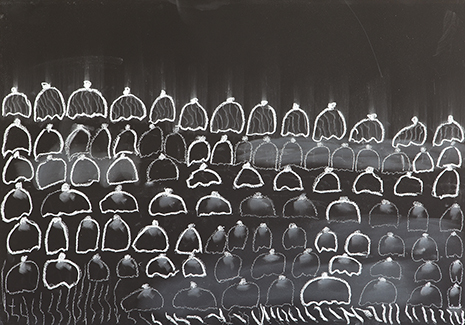

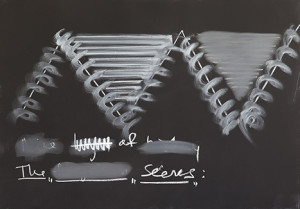

Memory drawing of Sophia Lehulere (2015, chalk on blackboard, 70 x 100cm) of ‘Untitled’ painting by Gladys Mgudlandlu (undated, gouache on paper, 51 x 70cm), part of ‘History Will Break Your Heart’, of Kemang Wa Lehulere, 2015.

HE ‘SEES BLACK PEOPLE’. SO WHERE AM I?

The Fine Art Institutional Desire to Situate and Locate the Narratives of ‘Others’

Across many intersections of class, race, gender, physical and mental ability, sexuality- difference- we find that in situations presenting neutrality (read: ‘whiteness’, patriarchy) where one feels unseen, there is no choice but to see- for oneself, and for those who do not see you. This, as Du Bois originally put it, (but in relation to race exclusively, as in this case, other Black bodies remained unseen), is the ‘double consciousness’(1), and it describes the internal struggle of the navigation of spaces, for bodies for whom society was not constructed.

Speaking as an observer of what I understand to be ‘the art world’ in South Africa, and more specifically in Cape Town- a middle-class Black person (I use this term as a political identity, rooted in Steve Biko’s framing of people of color as ‘Black’, under a system of white supremacy (2) ) this piece is an attempt to reconcile personal encounters in various art spaces that seem to present multiple tensions between viewer, artist, art object, and gallery structure- due to the latter’s implied neutrality.

So, while Du Bois’ ‘double consciousness’ is of utmost importance, it’s failure is its absolute erasure of Black bodies that are not cis-normative men, and so in order to use it here, we might rather think on the notion of multiple consciousnesses, because the theory’s logic sits in the relationship it recognizes of any bodies not adhering to societal ‘norms’, that are attempting to make meaning within society.

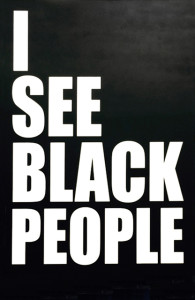

Ed Young, I see black people, 2015.

Perhaps, we might take Ed Young’s painting, ‘I see black people’ of 2015, as a departure point, illustrating with the languid, hip violence of the Cape Town art scene, the way Black people are often represented in this sphere, articulated through the lens of a careless and apparently humorous patriarchal whiteness. Movie references aside (3), the poignancy of the insult of this work is a useful example of a tired colonial desire to assimilate the Black body into spaces in a way that suits its own needs. This large black acrylic painting, adorned with its title text (‘I SEE BLACK PEOPLE’) in bold capital white letters is anything but self-reflexive, from its origin of white masculinity, and will function as a pondering point of anger we might use in fleshing out what such an object exposes about these spaces.

The Roles of Black Artists in South African Fine Art Culture

In South Africa, post-1994, it has become clear that many Black artists who are institutionally (and otherwise) trained are in a more likely position to gain success in the fine art world. This fact is of course, in many ways, a positive development. Our art world’s output is no longer only in the hands of those creatives descended from colonialism- those still benefitting from colonialism. However, let us not conflate output and content from notions of structure, circulation and institution. It does become important to explore what exactly happens to content when it is accepted into the so-called institution, or canon? Here, I think again from myself, the raw, the intuitive, believing in the necessity to process the sensory of the art institution- fine art culture, the fine art academy and discourse, art fairs, contemporary art exhibitions, ‘First Thursdays’ (4) – and explore what this institution enables, and what its functioning might erase.

Of course, it becomes very necessary to particularize this argument and articulate when this kind of consciousness might be useful, because the fact is, having Black artists operating more and more within the institution is important in itself- of course- but also in the way that it seems to shed light on exactly this structural lack. Implicit in fine art culture is that it should never be conflated with ‘other’ creativities, which simply cannot be regarded in these terms, due to the limitations of this uptight language. For if we want to talk about creativity, we might look to those who seek to curate through structural change, who are imagining spaces that take the notion of site specificity to mean the non-isolation of expression- the fact the creative exists only in context. This approach though- one that creates spaces in which oppressed bodies become the sites of original, and interesting knowledge production do not qualify, however, as fine art because in nature, they cannot take place in this institution.

If we shoot straight to the heart of the problem, using the Oxford Dictionary’s definition of ‘fine art’, as ‘Creative art, especially visual art whose products are to be appreciated primarily or solely for their imaginative, aesthetic, or intellectual content’, as a departure point, we can move from here to examine this in relation to the ‘contemporary’ and in relation to South Africa. ‘Contemporary fine art’ spaces then are those presenting themselves as isolated spaces in which ‘creative/ visual art’ can be ‘appreciated’. Even in definition, the obvious economic and structural aspects that enable this fineness of art are completely ignored, in favor of a fantastical and unrealistic viewing fantasy.

Although contemporary fine art galleries are commercial sites in actuality, fine art’s obsession with the purity of the gaze prevents it from explicitly expressing this cold, capitalist heart to its audience. In this sense (dramatic- I know), fine art spaces that come to mind in South Africa- spaces for the appreciation of contemporary fine art, are those like the Michael Stevenson, the Goodman Gallery, Gallery MOMO and SMAC, for instance, as well as institutional events like our International Art fairs.

That said, this article intends to tease out ways that these kinds of art spaces seem to currently unfold with relation to Black artists, viewers, and thinkers (Black people). It will also attempt to navigate the contradictions within the operation and structure of the gallery, and the larger fine art discourse set-up, questioning the forced norms of what it means to create knowledge- art- for ‘neutral’ spaces in South Africa. I guess when it comes down to it, I am just asking questions like, “why are there hardly any Black people in Cape Town gallery spaces, when the content here appears so attuned to ‘Blackness’?” and following this, “what does this tell us about the way Black people are situated then in relation to the gallery space?”, and more disturbingly, “why does a homogenous notion of Blackness fit so comfortably into what is supposed to be a creative space?”.

Essentially, when do we begin to ask the question of whether this falsified gallery context might pose direct danger to the reading of the artwork it holds? And how can we imagine this context shifting- what, in fact, might the shift of the ‘white cube’ look like?

An Applicable Institutional Critique?

Of course, institutional reflection and critique (of Ed Young’s type) is the very heartbeat of the fine art institution, and the art museum particularly has a long history of this kind of self-referential, if not self-reflexive scrutinisation.

What I have noticed from being an art viewer, and art student (in South Africa of all places!), is that when we talk about fine art, we are talking about a physical and conceptual structure that implicitly claims to ‘transcend’ national boundaries- a ‘white cube’ in every sense- adhering to its own standards of how art should be contextualized, where real art should be taking place, and how it should be read and canonized according to these standards. We might go as far as to frame this white cube obsession as a hangover that has somehow not been shifted by multiple western post-modern art and thought movements that successfully (but theoretically) dismantled the falsity inherent in the art museum/ institution proposing itself as a space of cultural mystique, divorced from the unequal status quo of capitalist society. This kind of engagement necessitates an understanding of the site of the institution, exploring its tendrils- acknowledging its ‘ness’ in society, and therefore having implications beyond the artist, the art product, and the gallery walls. This space affects the viewer in a multitude of ways, most complexly, those viewers whose experience and personal history has no relation to it- those whose consciousnesses are multiplied by the exclusivity of fine art discourse.

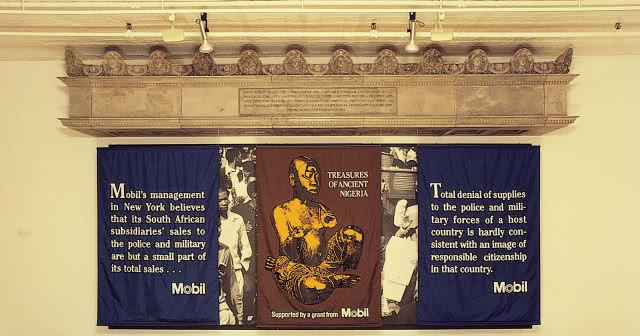

Hans Haacke, MetroMobiltan, 1985, fiberglass construction, three banners, photomural, (355,6 x 609,6 x152,4cm) (5)

Of notions of this viewer, Travis English in his 2007 paper, Hans Haacke, or the Museum as Degenerate Utopia, writes the following, with relation to the artist’s textual and visual intervention work:

The visitor… performs the narrative without realizing its mythic quality or, for that matter, its narrative quality; ideology serves to naturalize constructedness, to deceive the visitor into seeing harmony between real tensions and conflicting elements. It is only through meta-analysis that this mythic structure is exposed, and along with it the tensions and contradictions, the real relations of capital, begin to emerge. (English, 2007)

In South Africa- here, now- it might be of particular relevance to follow through on the modes of thinking employed in Haacke and English’s institutional critique, recognizing that not only is the space of South Africa’s national racialized, gendered and economically un-equal, the addition of the colorist apartheid system to the existing colonial one added a complex hierarchy of ‘rights’, which I would argue, was solidified in many ways through the post-1994 liberal, and strategically inaccessible constitution.

The art world, in this way, functions very similarly to the constitution- a holy document- claiming implicitly that it exists in a state of motion, a state of unfolding and is ‘engaged’ in the relatively permanent and chaotic political unrest in the country, whereas, in fact, it is a document that rolls out the same tired justice system because it exists, essentially, in a structurally identical space to that of pre-1994. In the act of the art institution clinging to this trajectory of ‘engagement’, ‘transformation’ and ‘equality’ rhetoric but remaining the same, the contradicting status quo immediately betrays it as an active trader in South Africa’s strategized and pervasive inequality.

Subversions that Are Impossible To Ignore

That said, however, there are many fine artists practizing in ways that subvert the traditional gallery spaces that their work exists in, and thus propose that the fact of their practices unfolding within the art gallery itself, presents a number of miscommunications and dissonances between art object and context. In this way, the gallery becomes a space of confusion, epistemological warfare, a challenge- it’s relationship with the work it exhibits is in many cases, a violent one.

Sophia Lehulere’s memory drawings of artworks by the late painter Gladys Mgudlandu, part of Kemang Wa Lehulere’s ‘History Will Break Your Heart”, 2015.

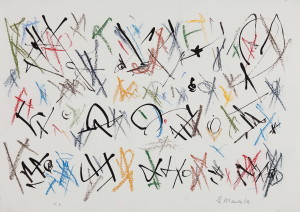

Ernest Mancoba, Untitled V 4, 1993, part of ‘History Will Break Your Heart’.

Here, Kemang Wa Lehulere’s 2015 ‘History Will Break Your Heart’ comes to mind, as an exhibition that employed a new historicist approach in its primary research of, and ‘collaboration’ with subaltern Black art histories in South Africa. Through an engagement with erased histories of practitioners Gladys Mgudlandlu, and Ernest Mancoba, Wa Lehulere exposed the art institution and discourse in which it was shown as the very context that had actively operated in excluding these narratives from popularized and recorded art history. Most appropriately in bringing this narrative of tension home was the fact that, as the recipient of the 2015 Standard Bank Young Visual Artist Award, the initial site for Wa Lehulere’s travelling show was (as with all Standard Bank Young Artist Winners), The Settler’s Monument (6), in Grahamstown, home also to Rhodes University.

With the work of these Black recipient artists in recent years being curated into an institution that articulates itself proudly as belonging to the ‘settlers’, we are faced with a conundrum. How do we understand work that speaks to our own histories, when the site of their conversation is silencing? How do we engage in a world that uses ‘Blackness’ in order to continue a cycle of economic, pseudo-cultural exchange, and a world that re-enforces already existing oppressions for its own gain?

Of course, in contemporary and recent fine art discourse, as the role of curators has become so central in the ‘creative process’, there seems to be a heightened awareness of art object relationships with one another, how their context functions singularly and collectively, and what the role of site-specificity is in creating meaning. This rigorous curatorial moment has allowed us to expand on notions of context and meaning, garnering new methodologies, and new approaches- but only within a pre-given context.

The curatorial contradictions are therefore rife, because we see a failure on the institution’s part to re-structure, and indeed, turn upside-down, a western culture that chooses to tell Black stories on its own terms. We arrive at a white man ‘seeing’ Blacks, ‘legitimizing’ our existence; we arrive at a limited conception of how meaning is created, and how it is translated. For how is it that we can all be talking about our own histories, all be producing, writing, and viewing art, in the same space, using the same white cube?

So, to get back to my original inference, we are stuck here at the problem of the multiple consciousness, where anyone departing from the hegemonic fine art norms of cis-masculinity, and of whiteness, must begin to attempt to see them(our)selves as if from the position of these ‘norms’, in order to navigate the space. We become negations; simultaneously we exist in the space, and must understand that our personal histories are erased by the space, and so we operate as ‘half people’, overwhelmed by the simple contradiction of our presence as ‘other’, even when what we are producing seems to occupy the space. Of course, this line of thinking is an attempt at some form of ‘integration’ of creativity- what does it feel like to enter an art space as an entire body, a history, a person with a knowledge and a story?

In following through on this, it is therefore apt to reflect on the multiplicity of consciousnesses I have experienced in producing such a text.