To gaze at the artist’s work is to encounter the vagaries of history, to be fixed in a time mitigated by the whims of the clock, an arbitrary sequence that fails to account for how Black femininity exists both within and without modernist time.

Sihle Motsa on the work of Frida Orupabo

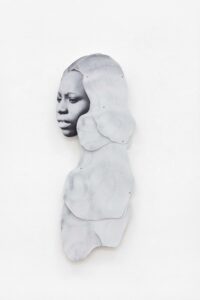

Lies, 2022

Hours After:

Frida Orupabo: Tale of Temporal Estrangement

The schism between the first world and the third is one mitigated by time. This was made poignantly apparent by a recent trip to the United States of America where the railways litter the body of the settler colony. Taking the subway was a dizzying experience, not because of the euphoric enchantment that usually comes with experiencing a new place, but due to the heart wrenching feeling that is accompanied by the realisation that the USA, considered the sin qua none of the modern world, a place that many consider a Mecca of sorts, is the site of your temporal undoing. The subway with its complex networks, sophisticated engineering and high paced tempo, represents one of the two ways through which time has been colonised. The other being the invention of clock time.

Burden, 2022

In a powerful treatise on how time structures social life, sociologist Barbara Adams makes clear that the quest for time control has been precipitated by a desire for economic gain, i.e., colonisation (1). This has been achieved through the invention of clock time. Clock time is the last of five C’s associated with the usurpation of time from the natural and supernatural into the hands of man, the other four being the compression, commodification, colonisation and control of time as a resource. In Adam’s resounding terms, clock time is a human creation. It is a decontextualized empty time that ties the measurement of motion to expression by number. It is a vapid constituent that measures not change, creativity and process, but assigns static states a number value in the temporal frames of calendars and clocks (2). The railroad, on the other hand, is bound to a global capitalist technology.

Company, 2022

Around 1880, retired Canadian railway engineer, Sir Sanford Fleming, began researching clock time and the astronomic conditions which it had been made to contain. This was in an effort to resolve the obstacles posed by the poly-temporal times through which the railways that crisscrossed America operated. Fleming’s resolution lay in the adoption of a standard time with hourly variations according to a system of time zones. The 360 degrees of the globe were divided by fifteen degrees owing to the idea that the earth rotates 15 degrees every hour. Thus, the globe was to be apportioned into 24 lines of longitude, each corresponding to a particular clock value. Fleming’s propositions on the standardisation of time where seminal to the meeting of the 25 presidential delegates who in 1884 gathered in Washington D.C and adopted what has become an internationally accepted time standard.

Evening Dress, 2022

The story of the railroads is also one with a more sinister historical undercurrent- that of indentured and slave labour, of genocide and large-scale land dispossession. The extractive labour economy allowed the creation of a sophisticated technology that stands today as a prime example of the compression of space and time. The railway as an imperial technology instrumental to the recreation and affirmation of capitalist time. Its infrastructures are the products of colonial extraction of labour, mineral resources and time. The railways’ status as the epitome of modernity is maintained at the expense of the zone of extraction. For the North America Continent to be in-time, in the modern, within reach of a comprehensible future, the black, the indigene, the Mexican must be exiled from the modernist temporal stage. The zones of extraction must abide by a split temporal order, a series of discombobulating times, repetitive, stagnant, elusive, irredeemable and all antithetical to the time of the modern. And so, in the words of poet and feminist writer Sonia Sanchez, “I had to get out of there you know”. I rebooked my flight twice, trying to get out of the maze as quickly as possible. I made it back to South Africa, a somewhat differently cognitively estranging temporal terrain in time for Frida Orupabo’s first solo exhibition at the Stevenson Gallery in Cape Town.

Hair roller, 2022

Aptly titled Hours After Orupabo’s collaged scenes work through what it means to be in and out of time. They think through what it means to exist in the precarious space of exile and labourer- where your authentic being is not welcomed at the altar of capitalist time even though it is your body that sustains modernity. In the gallery space the black, white and grey cut-outs are pinned to the glaringly white walls. The two-dimensional images are not framed. Hence their installation gives them a particular being in and out of space. Their unboundedness ensures that they exist in an expansive temporal field, making visceral the ontological struggles that emerge as a consequence of being out of time. This complex positioning of the work within and beyond the temporal makes apparent the ways time is tethered to space. This is because the feeling of time – that which Edmund Husserl defines as being pervasively familiar – is perceived through space (3). This invocation of space and its weddedness to time conjures Albert Einstein’s speech on Time, Space and Gravitation, wherein he maps the extent to which space and time unravel into the infinitesimally deep dark cosmos as sisters in arms (4).

On her mind, 2022

Einstein’s allegory of the train describes the fundamentals of this relationship. Einstein informs us that o describe the motion of a body we must refer to another body. The motion of a railway train is described with reference to the ground, of a planet with the total assemblage of fixed stars (5). Time is the silent essence that mitigates these relations. The train’s motion in relation to the ground of any other body is a function of time, so too is its stagnancy. The time of Orupabo’s images- cut out and reassembled is accessed through their relation with the gallery space, producing and uncanny sensorial effect of the Freudian type. The uncanny, whose linguistic and conceptual value which Freud traced through the German terms Heimlich which loosely translates to homely or familiar and unheimlich which translates to strange provides a mechanism for articulating the sensorium precipitated by Orapabo’s imagery (6). Orupabo’s artistic genre generates an uncanny affect in that its images work through a familiar colonial archive yet their fragmented nature produces a strange sensorial affect. By working through the archival, stitching imagery that conjures the colonial imperative, Orupabo’s works produce an affective sense whose familiarity and cognitively estranging qualities are emblematic of what it means to be in and out of time.

Pink Stockings, 2022

The artist’s oeuvre is haunted by the body of the black femme, an imago that Selamawit Terrefe reminds us is a figuration both outside and in excess of not only language but also the specular (7). Orupabo’s practice draws us to the ways through which black femininity is spectral. Through the suturing of mostly black women’s faces and bodies to colonial era iconography we coms face to face with the ways black femme is overburdened by symbolic repertoires that defy language. Black femininity as a historical and political construction is always an amalgamation of conflicting narratives of gender, sexuality, extraction and labour.

The Black femme is also always out of time, that is- beyond time’s social and political registers. Whilst Orupabo articulates this timelessness through the idea of waiting, a temporal phenomenon that describes a feeling of anticipation, we are also entreated to envision the ways black women are robbed of time, how time is extracted from their bodies, through the outsourcing of their nurturing, domestic labour and capacity for (providing) pleasure.

Reclining woman II, 2022

Against the white hard backdrop of the gallery space, mostly Black femme bodies are sutured to a myriad of colonial and popular iconography, a ploy that maybe read as an allusion to the ways Black femininity is perpetually entangled with whiteness. Black femininity is constructed through the colonial encounter. It is not simply another type of femininity but give credence to the fantasy of whiteness. Black bodies emerge through a searing background to indict us and our linear understandings of time. They beckon us to view the Black femme body as one that emerges through a particular violent historical epoch and to view the black femme imago as one that has yet to be liberated from that time.

Untitled (Spider II), 2022

Orupabo has revealed that the images are not sourced from traditional archival sources – libraries, museums and other such entities that figure in the public imagination as properly archival – but from the internet. Theirs is not a matter of a past that must be painstakingly excavated, rather they are part of the present’s circulatory regimes. They live and breathe amongst us. Orupabo’s works speak through the language of the archive, an entity whose discursive boundaries are delineated by a continuous, complex and confounding temporality.

To gaze at the artist’s work is to encounter the vagaries of history, to be fixed in a time mitigated by the whims of the clock, an arbitrary sequence that fails to account for how Black femininity exists both within and without modernist time.