From October, 4th 2016 to January, 15th 2017, the Musée du Quai Branly—Jacques Chirac in Paris presented The Color Line: African-American artists and segregation. The exhibition concluded with an exciting day and half symposium bringing together eminent specialists in American art.

Helene Beade reviews this exhibition within the context of France/Paris.

THE COLOR LINE IN PARIS

An impressive catalog was created for the occasion as well as a documentary in English or French which I highly recommend because it brings valuable information not addressed in the exhibition. It gathers interviews of specialists like Richard Powell or Robert O’Meally , artists, but also important collectors who countered the invisibility of works of African American artists in the museums in the United States from the 1960’s to the beginning of the 1990’s. Indeed in the mid-1970’s one could rarely go into a museum or a gallery in the US and find works by African-Americans. It was also rare to get a chance to study them as there was little written on the subject at that time. Museums occasionally had shows of African-Americans but they didn’t display the works on a permanent basis. Pioneers like Walter Evans started collecting and fulfilled the usual role museums. Today, a market has grown up around fashionable galleries and popular auction houses. Museums and collectors are making acquisitions, recognizing that there is a history that precedes them and that today’s younger artists are part of a tradition. It’s impossible to look at the 20th century and to ignore prominent artists who happen to have been black. According to Richard Powell, ‘It is true that institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Gallery are finally incorporating important works by important African-Americans artists in their galleries.”

The catalogue.

The musée du Quai Branly wished to participate in this movement. Stéphane Martin, President of the museum, clearly stated that the main purpose of this exhibition was “to restore the works and their creators to their rightful place.”

AN EXCEPTIONAL OPPORTUNITY FOR A FRENCH AUDIENCE

I was surprised and delighted to learn of an exhibit devoted to African-American art in Paris. It offered a rare opportunity for me, passionate about jazz, art and the history of African-Americans. Today there is almost nothing in Paris representing art in general from the United States on a permanent basis. The American Museum of Giverny closed its doors in 2008, only the Mona Bismarck American Center and The Terra Foundation Paris Center promote a greater understanding of American’s artistic and cultural heritage for the benefit of a diverse audience.

So I explored this exhibition carefully, mindful of its extraordinary character.

The Octoroon Girl, 1926 (Courtesy Michael Resenfeld New York)

The exhibition was wide-ranging and ambitious. There were numerous exchanges between the curator, Daniel Soutif, a lecturer in philosophy and art critic, assisted by art historian Diane Turquety and distinguished American scholars like Richard J. Powell, author of works including Black Art: A Cultural History (1997 & 2002) and Cutting a Figure: Fashioning Black Portraiture (2008), and Professor David Driscoll who made a brilliant presentation at the symposium on ‘Black aesthetics’.

The curator gathered 600 works and documents covering different artistic fields (visual arts, literature, cinema and music). Some of the artworks and documents were borrowed from private foundations, galleries, collections, and two museums in France: the Musée du Temps in Besançon and the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac. The majority of the artwork came from the other side of the Atlantic, from galleries and museums in New York, Washington, Philadelphia and Detroit. It was a joy to have access to rare historical documents and an impressive number of works by major African-American artists only rarely available to Europeans and never before shown in France.

THE ‘COLOR LINE’

The expression ‘color line’ was first coined by Frederick Douglass in an article published in the North American Review in June 1881, less than 20 years after the end of the Civil War (1861-1865) and the abolition of slavery (Emancipation Proclamation 1863/ 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution 1865). The term refers to the segregation of black people that began in the United States in 1877 after the Reconstruction period.

What is called ‘Black art’ in the United States thus emerged in a political context and its founding act was the staging of the emancipation of the black people in 1867.

Melvin G. Johnson, Self-Portrait, 1934.

Edmonia Lewis sculpted a piece called ‘Forever free’ that is now exhibited in a gallery of the historically black Howard University in Washington. It was presented to us, visitors in Paris, in a video. This piece is important as it is considered as the first major work created by a black American woman. The sculpture, made from white marble, represents a free man and woman breaking their chains. It was a shocking way to say that ‘this is our classical story as if this story of slavery belonged alongside stories of the Greek Gods’. The work is considered optimistic, depicting someone’s achievements.

Yet, it stands apart. The hope offered by the abolition of slavery did not last long. The segregation and disenfranchisement laws known as ‘Jim Crow’, a kind of codified apartheid, were introduced in 1890. These laws were to dominate the Southern United States for three quarters of a century. Under the Jim Crow system ‘colored people’ received ‘separate but equal’ (Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896) treatment under the law, upheld by local government officials and reinforced by civilian acts of terror. ‘Black art’ became more pessimistic in the late 19th century as rights were thus taken away.

POSITIONING

The guiding line Daniel Soutif chose is in the exhibition’s title. The objective was to analyze the impact of the invention of ‘the color line’ on the creation of many African-American artists and on the writing of art history. The exhibit poses the question: how did African-American artists respond to this color line, this line establishing segregation in the United States? To do so, curator Daniel Soutif chose to cover the entire period from the abolition of slavery to today. The exhibition’s aim was to offer a tribute to the African-American artists and thinkers who, throughout a century and a half of struggle, contributed to blurring that line.

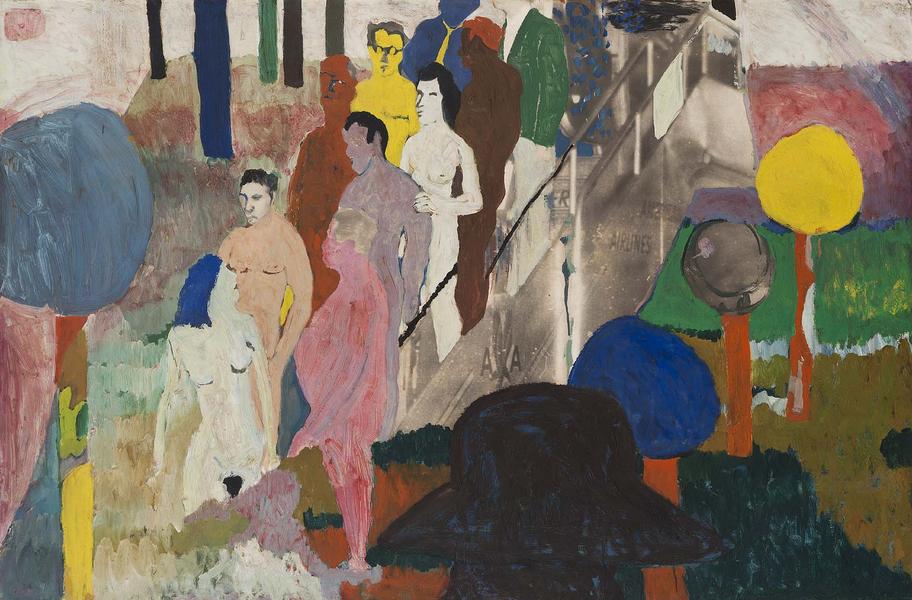

Bob Johnson, Stairway to the Stars, 1962.

CURATING CHOICES

Why an exhibition of both art and documentation?

A personal choice

When Daniel Soutif began work on this project, the initial mandate from the museum was for a documentary exhibit. The idea was not at first to place special focus on art’s contribution to this question. His idea was exhibit of artworks. His focus was above all on the curatorial, and he was anxious to see the artists and appreciate their work on its own as one is accustomed to doing today, presented in white spaces void of context. This may not be the best solution to appreciating the works, according to Daniel Soutif, but it is what we are accustomed to, the white cube inside the white cube.

The audience.

The curator thought that the audience would be coming to the exhibit supported with documentation. Why? Simply because of the general social context of people likely to be interested in this kind of exhibit. In this view, the audience came for general information on American history.

Whitfield Lovell, Autour du Monde, 2008.

During the symposium, Daniel Soutif developed this view: ‘I think that current affairs are much more prominent than history. In France one might know Ferguson because the journals talk about him. If I mention Frederick Douglass I little chance of finding someone who knows who that is. If I mention Glenn Ligon, I have a chance that a curator of modern or contemporary art will know who that is. But if I mention Archibald J.Motley I’m almost sure no one will know who that is.’

So Daniel Soutif decided to contextualize all of this because terms like reconstruction or Jim Crow have little resonance in France. The audience may know something of the effects of segregation but not that there were laws, amendments, and almost a hundred years of struggle accompanying the period of legal and actual segregation.

As a consequence, the curator made the choice of a mode of exhibition with both documentation and art works in a purely museum context. Yet he wanted to propose to the audience two modes of visibility in the exhibit, without distractions or questions of intimacy. The solution he found was to concentrate the documentation on the walls in horizontal cases, except in the room on the Harlem Renaissance, where the original documents were not visible until one would approach them and turns ones back on twelve documentary walls in fourteen sections. There were only two rooms… one on the boxers and one on the First World War, and less successful solution on account of the overwhelming presence of documentation. The idea was to offer the audience the possibility to explore the exhibition as an art exhibition. The documentation being accessible in most cases only if you came close to the horizontal cases.

Benny Andrews (detail)

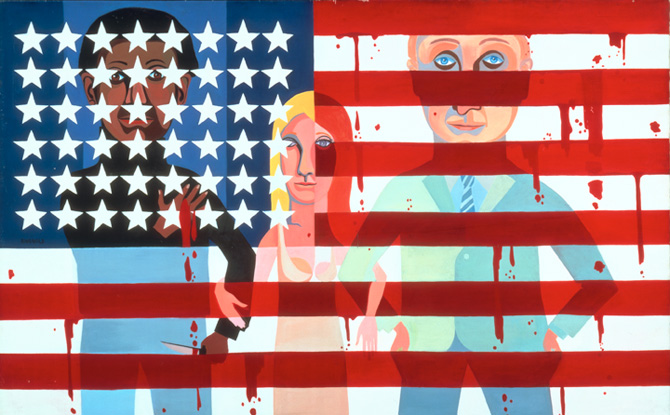

Faith Ringgold, American People Sries, 60’s.

Yet a polemic choice.

‘The Color Line’ exhibition is in a tradition of exhibits poorly known in the United States but it used to be more common in France. Daniel Soutif, coming from the tradition of the Centre Pompidou, was inspired by early exhibits at the Centre, points of reference for almost everyone in the world of art in Paris at the time. The exhibits Paris-Paris and Paris-NY or Paris-Moscow aimed to provide both documentation and artworks, and to contextualize and treat different objects differently. This could have been a utopia as this tradition never really lasted at the Centre Pompidou. Yet it is the choice Daniel Soutif made. Nevertheless, despite of all the valid justifications the curator offered, one can pose the question of the place of archival material and images. Indeed, was the purpose of showing cabinets of old catalogues really achieved? Why display so many documents?

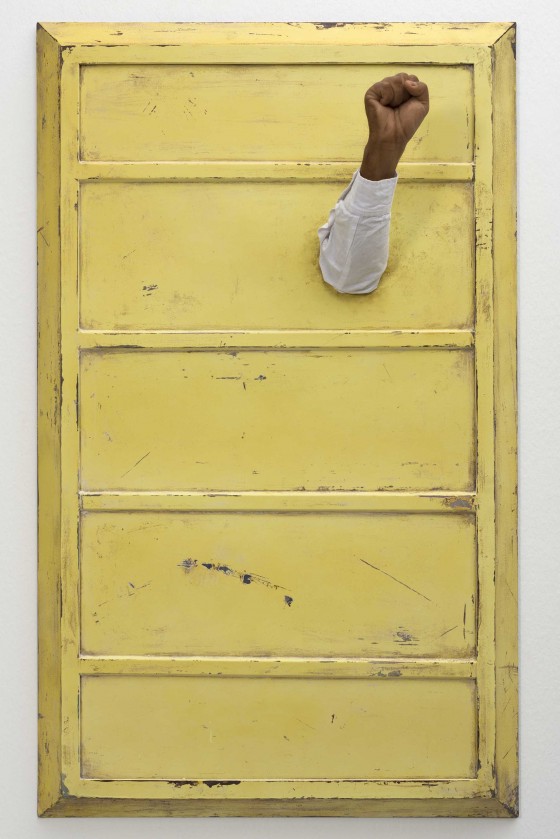

Hank Willis Thomas, Amandla, 2014.

What is more, the debates around exhibits like “The Great Migration” at the MOMA, accompanied by documentation, which resembled the approach taken at the Centre Pompidou were not devoid of interest. Some said at the time that the MOMA had done this because it was a black artist, an artist located in the usual narrative. They further argued that the museum would never have done this for Jackson Pollock or Piet Mondrian.

Were all African American artists ‘political’?

According to Richard Powell, it is ‘almost certain that black artists must have realized that they had a particular burden and a particular challenge not just to do exceptional work but to show a new representation of black women and black men that might speak to humanity, to dignity, to beauty in a way that was really against the tide of popular culture.’ The chosen works were for the most part touched by the history of the ‘color line’, in very explicit and more subliminal ways. Nevertheless, African-American artists did not necessarily obsess with radicalism or the political. For instance, if the works of Glenn Ligon have an explicit link to the question of segregation and even discrimination, things are less simple in the work of Norman Lewis. The works shown in the exhibit may have been shown in that period but in a debatable way. I wish the exhibition had tackled some the following question: How did artists respond to this question and to each other?

1856-2016. WHY COVER SUCH A LONG PERIOD?

Daniel Soutif made the ambitious choice to cover a very long period as Mark Godfrey, Curator of

International art at the Tate Modern, underlined this challenge at the symposium. He is currently preparing an important exhibit due to open 12th July 2017, ‘Soul of a Nation. Art in the Age of Black Power’ (with Zoe Whitley). That show will attempt to tell a different story, that of the art made between 1963 and 1983, a much shorter period. It was a time of frustration, the beginning of black power, and the civil rights movement. A time of institutional and political turmoil. A time when there was a lot of pressure on artists to address questions like: is there such a thing as a black esthetic? Is there black art? Did they like being asked by journalists’ queries like, is there black art? Mark Godfrey would have also liked to answer the question: what does it mean to be a black woman artist? Yet, this question will be tackled soon in the Brooklyn Museum’s ‘We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965-1985’ (April 21-September 17), curated by Catherine Morris with Rujeko Hockley.

Two interesting exhibitions that one should look at closely.

Robert Colescott, Knowledge of the Past is the Key to the Future (Saint Sebastian), 1986.

CONCLUSION

I left the museum with mixed feeling that persist today.

I appreciated the pioneering character of this exhibit. Daniel Soutif’s goal of introducing essentially unknown artists to a French audience was laudable and I think in the sense the curator succeeded.

I also felt relief after having seen the radical changes in the situation of black artists at the end of the 20th century. A new way of stating one’s identity has emerged. African-American contemporary artists, while still recognizing past combats, have started to allow themselves distance and humor. They are liberated from the political constraints which weighed down their predecessors. They do ‘not have the burden of being strictly tied to a political or an uplift positive agenda and that makes their work exciting but it also sometimes makes their work very provocative.” (Richard Powell).

I was interested in seeing how and what to create in such a context, as an African-American artist. How artists had to struggle against negative images. How they tackled on taboo topics or stereotypes head on without over-simplifications, and debunked them one after the other. But also how did these artists work to come out from their invisibility. For instance, in Horrace Pippin’s painting The End of War, white German soldiers are visible while black soldiers blend into the background and the earth. Or, part of what Whitefield Lovell attempts in his work Autour du Monde is to make the black soldiers visible, restoring visibility to men history forgot, acknowledging them as human beings who were more than just background.

I was pleased to see that it seems that at last we are witnessing a rewriting of the history of the 20th-century art to include black artists, as the New York Times would have us believe? (11/29/2015).

YET I could not help thinking that it it’s kind of late. I rather agree with Richard Powell: ‘These artists have been recognized by a cohort of scholars and patrons, art historians and collectors for a long time. And while you could not see that work at the National Gallery or the Metropolitan Museum of Art, you could see that work at the Studio Museum in Harlem, and at historically black colleges and universities, so better late than never.’

Nonetheless, it was clearly shown in the documentary film that most of the artists presented in the show wanted to be recognized as artists, and not just as black artists. To quote one example among many others, ‘Why should the color of my skin (…) forever influence what I paint? Henry Ossawa Tanner asked.’

In keeping with this idea, one can understand certain artists’ refusal to participate in this kind of exhibit. I think of Adrian Piper, who refused to participate on two grounds: in a statement, she did not want to be considered either as a woman nor as an African-American; and, she also refused on account of the nature of the project, stating her disagreement with projects defining a group of artists on the basis of their appearance.

So I left the museum hoping that this kind of exhibit, organized around the skin color of an artist, would be the last. This ground is shifting below us today; consequently, let us hope that this exhibit will mark a larger movement with more monographic exhibitions in large French and international institutions.