The topics raised in the Diaspora Pavilion are deeply serious and function within a discourse that has been going on for the past decades, in which the former ‘other’ is claiming an equal and independent position within today’s world, according to their own narratives, not the ones put forward by the former oppressor.

Robbert Roos on the Diaspora Pavilion in Venice.

Yinka Shonibare, The British Libray, 2014 (detail)

Outside the framework

The Diaspora Pavilion in Venice

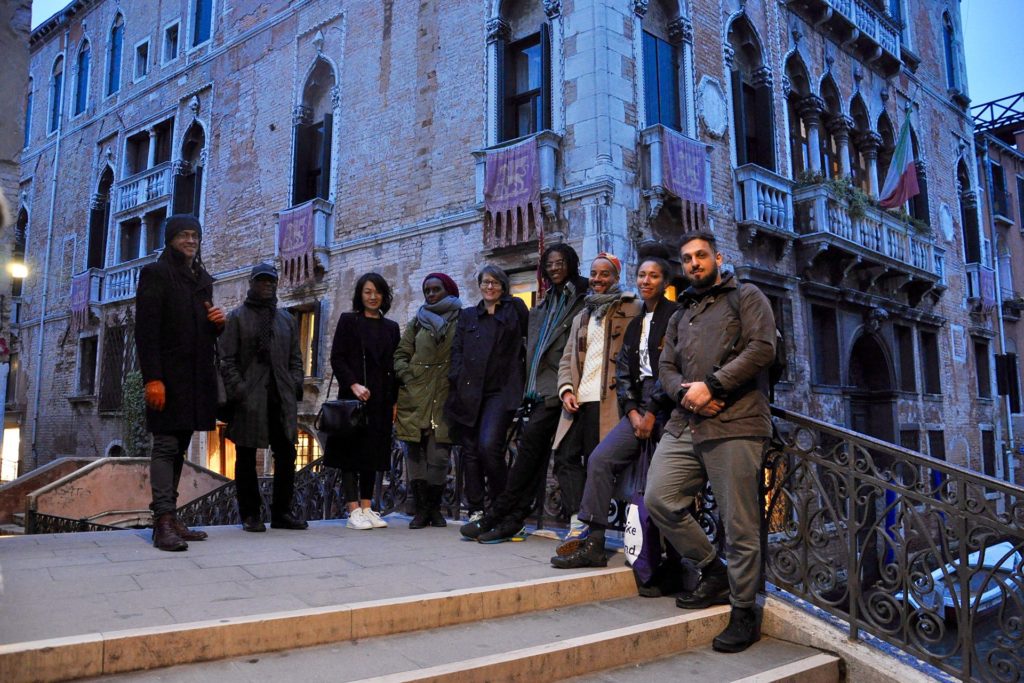

In a small Venetian alley the entrance to the Palazzo Pisani is obscured by shimmering golden plastic strings. If you didn’t know better, this could be the entry to a nightclub or a party place. Instead you are entering the Diaspora Pavilion, one of the highlights of the side program of the 57th Venice Biennale. The pavilion is set up by the ICF, the International Curators Forum, and is part of a larger two year program called ‘Diaspora Platform’ that ICF runs together with UAL, the University of the Arts London. In this program eleven ‘mentors’ (ranging from Hew Locke to Yinka Shonibare as well as Ellen Gallagher, David Adjaye and Isaac Julien) team up with twelve emerging artists, whose works engage in the topic of the diaspora. The Pavilion is one of the first occasions where both groups – mentors and supported artists – showcase their work together, curated by David Bailey and Jessica Taylor.

Diaspora Platform.

Of course the positioning within the context of the Venice carnival is significant. As the statement reads: ‘The Diaspora Pavilion is conceived as a challenge to the prevalence of national pavilions within the structure of an international biennale and takes its form from the coming-together of nineteen artists whose practices in many ways expand, complicate and even destabilize diaspora as term, whilst highlighting the continued relevance that diaspora as a lived reality holds today.’

The topic of national representation is never far away when dealing with the context of a biennale in which ‘countries’ represent themselves. But who do they represent? Increasingly we see a wide range of participants in the ‘national’ pavilions that cross the border of those countries or reflect mixed origins. Germany and France swopped pavilions in the Giardini a couple of years ago, the Brit Nathaniel Mellors is co-artist in the Finnish pavilion this year and already in 2003 The Netherlands hosted an exhibition called ‘We Are The World’ in which artists from Mexico, Benin, Italy and The Netherlands mixed. Several of those presentations touch on issues of the ‘diaspora’, but never so explicitly as the Diaspora Pavilion.

The term ‘diaspora’ reflects the painful history of displacement, forced labor, imperialism and colonization and this history is therefore etched into most works in the presentation. After the ‘Magiciens de la Terre’-show in Paris (1989) opened up the ‘western’ art historical canon to accept ‘non-western’ art as an equal part of the family, much has been done to integrate artistic voices from all parts of the world into the holy centers of the ‘western’ art world: museums, galleries, biennales, themed exhibitions. First as a more or less exotic extra, later on a more equal basis. Always, however, it was the ‘western’ art world deciding on the conditions of the stage. Time to take matters into their own hands for artists of various origins, identities and context. And hence the Diaspora Pavilion, an autonomous voice within the Venice spectacle.

The curtain of Susan Pui San Lok is a ritual of sorts. You leave behind the old streets of Venice – a city representing much of the former European glory – and enter a different world. Before you have time to shake of the last threads of plastic gold, you are confronted with a flotilla of ships, hanging on eye level ‘sailing’ towards you. Each ship is decorated with a mix of cultural icons and mystical talismans. Inevitably the mind drifts to the ships with immigrants that try to cross the Mediterranean Sea to look for a better life, as Venice itself has a long history as a refugee city but also as a trading hub; a hinge of sorts between south and north. This gives the installation of Locke multiple readings. The tone is set.

Hew Locke, On The Thethys Sea, 2017

Hew Locke, On The Thethys Sea, 2017

The strength of the Diaspora Pavilion is the variety in artistic positions. Charged, but not overtly pamphletistic, building on visual power, poetic renderings of personal ideas and, yes, strong politically comments referencing historical and contemporary issues regarding colonialism, immigration, identity and displacement. It is a meandering exhibition that captivates from start to end.

Barby Asante, As Always a Painful Declaration of Independence: For Ama. For Aba. For Charlotte and Adjoa, 2017.

Barby Asante can be found throughout the pavilion. Already in the staircase the steps are lined with votive candles with the image of various black women. On the first floor a bed is covered with a silkscreened historical picture of a grandiose African woman and in another room we see a kind of study with various artifacts and – again – votive candles with associated images alluding to people that were important for the artist. The everyday as presented by Asante is intersected with a mythical past, mostly people she holds dear that function as a kind of talisman and reflect the history of her people still relevant in the reality of today. The title of the series of works – ‘As Always a Painful Declaration: For Ama. For Aba. For Charlotte and Adjoa’ – is taken from a poem by Ama Ata Aidoo, who speaks about independence not only of Africa from the colonial rulers, but also as a break-up between lovers, with the possibilities for women to be independent. Those voices are heard in Asante’s installations.

The idea of the past being relevant for the present is also an aspect in the tintype self-portraits of Kadhija Saye, in which she mimics spiritual gestures of Gambian healers. The photographic technique gives the photographs the aura of being old and nostalgic, further intertwining past and present.

Khadija Saye, Dwelling in this space we breathe, 2017 (Kadija Saye was among the victims of last week’s Grenfell Tower tragedy in London)

Barbara Walker made an impressive charcoal drawing in the stairway based on snapshots of British soldiers from the West Indies, who wanted to participate in World War I, but were sidelined in the periphery of the war and ultimately rebelled about the passive role given to them by the British Command.

Barbara Walker, Transcended, 2017.

Bacchus and Ariadne, 2004.

It is personal stories that trigger most of the works in the exhibition. Some however are more explicitly addressing a necessary re-write of history or at least an alternative take on history. The powerful paintings of Kimathi Donkor feed on ‘imperialist’ imagery, but instead of celebrating the ‘heroes’, he rewrites the iconography of the protagonists. Also his painterly style is a mix of ‘old’ European techniques and the approach of African (American) painters.

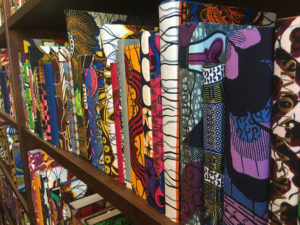

Yinka Shonibare – one of the mentors – created a library of books wrapped in Dutch wax, and on the back the names of immigrants that had a significant impact on British cultural life, both known and unknown, including several contemporary artists. An alternative cultural canon to be ‘read’.

In his critical review of the Venice Biennale for the New York Times critic Holland Cotter dubbed the show quite diminishingly as a bland ‘soft power’-exercise, out of sync with the political turmoil post-Trump and post-Brexit. For Cotter the humanistic view on the world put forward by artistic director Christine Macel doesn’t hold up. It was not political enough (he probably will have a better time at Documenta in Kassel). Supposedly ‘soft power’ doesn’t cut it any more, implying that stronger measures are necessary. Could that be the case for the Diaspora Pavilion as well? Although the whole show is about post-colonial reality, it is for the most part not an activist’s position. Rather the artists try to get their messages across to the hearts and minds of the viewers with eloquent artistic narratives.

Participants: Larry Achiampong | Barby Asante | Sokari Douglas Camp | Libita Clayton | Kimathi Donkor | Michael Forbes | Ellen Gallagher | Nicola Green | Joy Gregory | Isaac Julien | Dave Lewis | Hew Locke | susan pui san lok | Paul Maheke | Khadija Saye | Yinka Shonibare MBE | Erika Tan | Barbara Walker | Abbas Zahedi

The topics raised in the Diaspora Pavilion are deeply serious and function within a discourse that has been going on for the past decades, in which the former ‘other’ is claiming an equal and independent position within today’s world, according to their own narratives, not the ones put forward by the former oppressor. These stories need to be told time and again. History needs to be constantly checked, corrected and restructured. Until the fundamentals of this narrative will be an integral part of colonial history and a new constellation – with real ‘hard’ power for the formerly oppressed – can be formed.

On this level the Diaspora Pavilion functions very well. It is an autonomous voice, in an art context shaped from within the old ‘imperial’ art world. It is a framework structured by the people involved in the topics themselves. The question is for how long this will be necessary. This year Nigeria has its own pavilion – in a building next to the San Stae church. More countries will follow. Most artists in the Diaspora Pavilion have a connection to Great Britain. An artist like Chris Ofili has already ‘done’ the British Pavilion in the Giardini. And that is the big dilemma of the Diaspora Pavilion: the duality of it being a strong and powerful context to get the message of the individual projects across, but also a solidification of the participants as ‘outsiders’, that in some ways is cultivated with such a separate pavilion.