Recto

Living in the era of the selfie where many millions of people seem to be busy with their self-image, without political or social necessity, but just for fun or vanity or insecurity, in which that can happen effortlessly through the lightning-fast technical developments and in which those images in no time at all spread around the world, it may be difficult to fully appreciate the importance of these staged, historical photographs, photographs that, on top of that, cannot be massively distributed because they were made with cameras that immediately printed them on paper.

In this article Rob Perrée shows how important these historical photographs of black Americans were and still are.

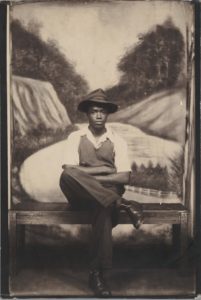

Unknown American maker, Studio-Portrait, 1940s-50s, Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Historical photographs of black Americans at The MET in New York

THE HERITAGE OF FREDERICK DOUGLASS

An exhibition in two small, overlapping rooms, pushed away in a corner on the second floor. On the website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the announcement of African American Portraits: Photographs from the 1940’s and 1950’s dangles at the end of the exhibition page. The explanation is only 5 lines long. Actually there is nothing in it. I could say that the museum, despite its long history, has not really excelled in presenting African American art, but that would be a “too easy “ justification. I could also think that it is only about 150 small photos, so why am I complaining. Nevertheless, I know that the importance of the exhibition deserves a better and more scholarly presentation.

On the walls and in a number of transparent, plastic showcases there are 150 photographs that were made in the forties and fifties of the last century, mainly in the south and mid-west of the United States. They are photographs of African Americans. This epoch represents a significant chapter in the history of the country. For the second time, many blacks migrated from the south to the north, because there was more employment there. In the Second World War many black American soldiers fought in Europe (though in separate units and with separate accommodations). The economic crisis that began in 1929 with the ‘Wall Street Crash’ and continued in the thirties, was over. The average American had more money to spend. Many Americans of color could also afford to have their photos taken in a photo studio in cities like Memphis, New Orleans and Charleston.

These facts do not say much in themselves. You can still find these kinds of photos, if you look closely, at flea markets, in messy antique shops and at home in the photo albums of hundreds of thousands of black families. Hanging them in a museum on the wall, does not make them important or more important in themselves. Many visitors will therefore wonder why a leading museum such as The MET harries flea markets to add, for a pittance, this kind of photos to its collection. The responsible curator clarifies this only in an indirect way.

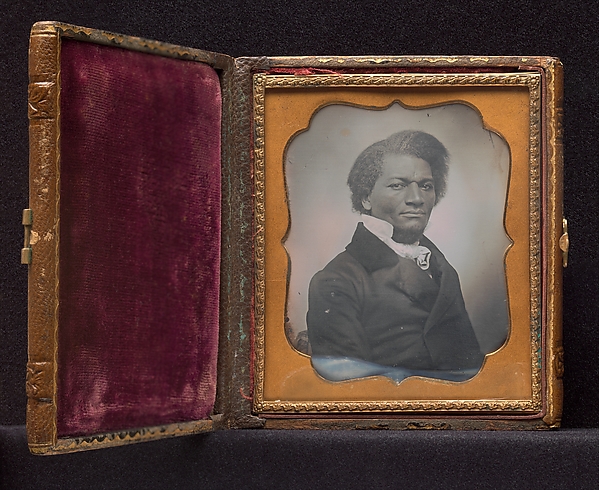

Unknown (American), ca. 1855, Daguerreotype, 8.3 × 7 cm, The Rubel Collection, Gift of William Rubel, 2001, Coll. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The exhibition starts with a daguerreotype portrait of Frederick Douglass, ‘wrapped’ in a small box, lined on the inside with red velvet. The photo is surrounded by a richly shaped, gold-colored passe partout. A display case protects the precious gem. You might think that the curator wanted to use this museum piece as a crowd puller, but he had a different intention with it.

Douglass – an escaped slave, probably born in 1818 – was a writer, a popular speaker, an active abolitionist and ultimately he became the US ambassador in Haiti. He realized the importance of photography like no other. (…)there is nothing in the wide world half so effective as the presentations of a character so precisely opposite of all their representations. We have it in our power to convert into positive blessings, the weapons intended for our injury he says in his famous speech ‘Pictures and Progress’ (1861). By letting himself be photographed, the black American can adjust the image that the average white person has of him. (…)even in the hands of a racist white, the camera would not lie, the historian John Stauffer paraphrases the words of Douglass. Douglass himself gives the good example. He is the most photographed American of the 19th century.

Against this background ordinary photographs become extraordinary photographs.

Even though the photos do not provide information about the identity of the ‘models’, they provide enough other information. In part, they are family photos intended for fathers who fought during the war and who probably felt protected by those photographs; for another part they are of anonymous young men or young women who, whether or not in pairs, whether or not for the celebration of a festive event, obviously pose for an, also anonymous photographer. It is the context that speaks. For example, there is a photograph of a young man, 12 or 13 years old, who has been photographed against a painted, rural background. He has a neat coat that is a few sizes too big. His pants are not his size either, because his trouser legs have been turned over. His right hand seems to take the receiver of a telephone on an antique table. He looks seriously into the camera. Such a photo raises all kinds of questions. Who determined the setting? The photographer? The kids’ parents? He himself? Was this consciously chosen for an upright appearance? Should that rural background symbolize an ideal world? Does that phone give the message that black children also share in the progress? Was the photographer black? In the words of curator Jeff Rosenheim: They tell stories that other stories from the same time do not.(1)

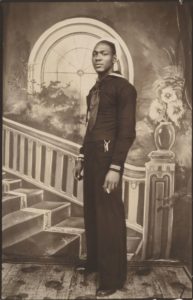

In another photo is a nicely dressed, attractive young woman sitting on a bench against the painted background of an almost tropical, seductive landscape. She looks contained cheerfully into the camera. Here too, it is easy to come up with a story that is at odds with the image that many white people have had of a black girl from the dark south of the US.

With a number of photos, the aesthetic appearance is enhanced by coloring details: by making lips red, by giving a flower on the painted backcloth a color or by embellishing the entire rural background with blue and green. This may have happened because the photographer could ask for a higher price, but it was also the intention to sharpen the positive tone of the image.

Living in the era of the selfie where many millions of people seem to be busy with their self-image, without political or social necessity, but just for fun or vanity or insecurity, in which that can happen effortlessly through the lightning-fast technical developments and in which those images in no time at all spread around the world, it may be difficult to fully appreciate the importance of these staged, historical photographs, photographs that, on top of that, cannot be massively distributed because they were made with cameras that immediately printed them on paper.(2) No negatives involved (by the way, from an art perspective they are more valuable by that uniqueness). That ‘shortage’ gives them the value of period pieces too. They belong in the collective memory of the American.

It is tempting to compare this studio photography with that in African countries. Originally the studios were run there by the European colonizers. They also staged the photos, but with a completely different purpose. The photographs were intended to send the exotic cliché image of Africa into the world in order to give colonialism a romantic look. Only when the African countries became independent did the Africans take over the studio photography themselves. So especially between the 50s and 70s. Photographs were then made that can be compared with the photographs in this exhibition, with a similar purpose as well.

Interestingly, a number of these African photographs are all the rage in the Western art circuit (see for example Malick Sidibé and Seydou Kiëta). As if that is not a form of romantization ? A lucrative form of romanticizing as well.

African American Portraits: Photographs from the 1940’s and 1950’s is an interesting exhibition that has been presented too modestly and that has not been given enough context for the average museum visitor to fully assess its importance.