The enormous drive for maintaining their traditions is probably the most important reason for the Ouattara brothers to make masks. As they were saying, many masks have been sold or stolen and are in museums nowadays, in Europe and the United States, but also in Africa. People are left with copies or reproductions of the masks they used before, as a result of which the meaning and the cultural significance of mask traditions has changed

Sanne Molenaar on the Ouattara brothers from Burkina Faso

The Ouattara Brothers

Reinterpreting traditions and appropriation

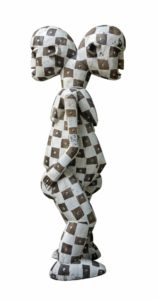

Having conducted research among many cultural groups in their home country Burkina Faso and other West African countries, Ousséni Ouattara and Assane Ouattara, who are twins, have a wide knowledge of African artistic traditions. The two brothers are living together in a shared court, with their wives and the rest of the family. A large part of the court is taken by their workspace, which is filled with mask reproductions and other objects they have made or collected. Most of the masks they have made themselves. While visiting a village, they often ask the elders whether they can see their masks. When returning home, in Bobo-Dioulasso, they use the information they have got to make a mask that is similar to the one they have seen, or to make a contemporary version of it.

Workspace Ousséni Ouattara and Assane Ouattara, Bobo-Dioulasso, 2019.

Why making masks?

The enormous drive for maintaining their traditions is probably the most important reason for the Ouattara brothers to make masks. As they were saying, many masks have been sold or stolen and are in museums nowadays, in Europe and the United States, but also in Africa. People are left with copies or reproductions of the masks they used before, as a result of which the meaning and the cultural significance of mask traditions has changed. Masks do not only have a spiritual function anymore; mask performances are also a form of entertainment and contribute to the social cohesion of communities. An example of this is Festima, a mask festival that takes place every two years in Dédougou, a town in north-western Burkina Faso. People from different cultural groups come together with their own masks, sharing their culture with other people both from their own country and from the rest of the world. The festival can be considered as a means to maintain the mask traditions, in the same way as the Ouattara brothers do.

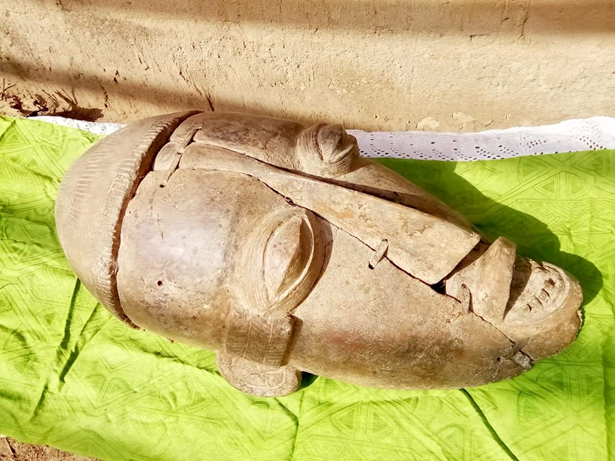

Ousséni Ouattara and Assane Ouattara. Bamanan fetiche. 2018. 53×20 cm. Terracotta, wood, leather.

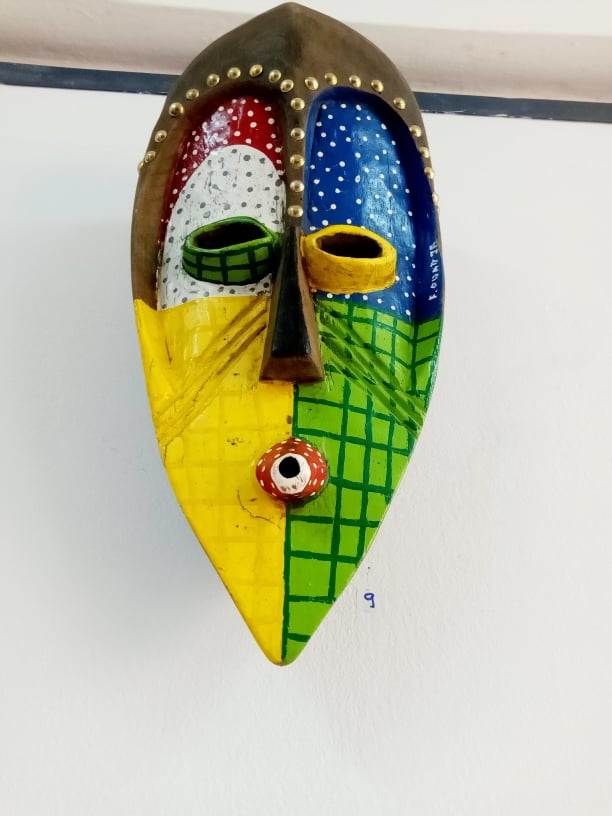

Ousséni Ouattara and Assane Ouattara. La marquise. 2018. 42×17 cm. Wood, paint.

For Ousséni Ouattara and Assane Ouattara, both copying a mask and interpreting it more artistically, are ways to hold on to their traditions, which are not only their own Bobo traditions, but also those of other cultural groups in Burkina Faso and the rest of Africa. From the 22th of November until the 6th of December 2018, an exhibition in the Maison de la Culture in Bobo-Dioulasso took place, where the brothers showed 39 mask copies, as they name them themselves. Although they use the word ‘copy’, most of the masks are actually contemporary interpretations. The reason why they do this is because the younger generation is not as familiar with masks and their symbolic meaning anymore as the elder generation is. Still, interpreting the way in which a mask has been sculpted, its decorations and the colors that have been used, is essential for understanding its value and social and spiritual meaning. By relating the traditional mask symbolism to the current society, they want to make the masks more accessible and easier to understand, for a wider public. They also organize guided tours through their exhibition, during which they explain every detail of the masks, and give accompanying lectures.

The mask ‘La marquise’, which means ‘The marquess’ is an example of such a contemporary mask. With its bright colors and the decorations that have been applied to it, the mask seems to have rather an artistic than a spiritual function. In this case, indeed, the colors have been used to beautify the mask. Although the shape of the mask refers to traditional mask styles, its meaning does not. This mask represents Guimbi Ouattara, a 19th-century princess from Burkina Faso, who is one of the few female political and military leaders in the history of the country. She is known to have protected Bobo-Dioulasso against the Tiéfo invaders, for which people still honor her today. The princess cannot easily be recognized from the mask, but the scarifications on her cheeks demonstrate where she comes from and its title ‘La marquise’ indicates a reference to an important woman. Despite the aesthetic appearance of the mask, it is not just an art object. Next to more traditional looking masks, this one also urges people to maintain their traditions, although indirectly. The mask form is used symbolically as a means to refer both to the importance of masks as such and to remember historical facts on which the current society and cultures are based.

Masks in museums

President Macron at the University of Ouagadougou, 27 November 2017.

In line with the valorization of tradition is the current discussion about the repatriation of art and other objects from European museums to Africa. As many of these objects have been acquired during the colonial times, often in an unequal way and sometimes even stolen, museums are now thinking about whether they should return parts of their collection to the African countries from where they come. On the 28th of November 2017, Macron gave a speech at the University of Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso, in which he announced his plans to return the African cultural heritage to where it comes from: “Le patrimoine africain doit être mis en valeur à Paris mais aussi à Dakar, à Lagos, à Cotonou, ce sera une de mes priorités. Je veux que d’ici cinq ans les conditions soient réunies pour des restitutions temporaires ou définitives du patrimoine africain en Afrique.”(1) Not only France, but other European countries amongst which The Netherlands, Germany and the United Kingdom, are considering a restitution of art and other objects as well. Recently, the Museum of Ethnography in Leiden, The Netherlands, has made a form that people and institutions in Africa can fill in, if they want to apply for having restituted an object, including the necessary conditions. Some objects have already been returned.

*

Ousséni Ouattara and Assane Ouattara take a remarkable position in this discussion. First, they emphasize that the masks and other objects that have been put in a museum, have lost their power, their spiritual power. Even if they will come back to Africa, they will not be used in the way they were before, because they are not the same anymore. The objects will probably be received by the Ministry of Culture and directly placed in a museum again, in order to protect them, or they might even be sold. According to them, a better solution would be to create a new museum, financed by the French state, in which the objects are shown in an honorable way, acknowledging the agency of the objects and their colonial history. In that way the objects will get the place they deserve and are at the same time accessible for everyone.

Ousséni Ouattara and Assane Ouattara are also collaborating with the Catholic University of West Africa in Bobo-Dioulasso, where they sometimes give lectures about their research on African art traditions. Their knowledge about African cultures and traditions is greatly valued.