The Kampala Biennial 2018 was not a normal one.

Curator Simon Njami chose to introduce a system that could make the contemporary artist. Since he is convinced that Kampala does not have contemporary artists worth showing–off to the world, he invited seven internationally acclaimed and foreign artists to train young artists from the city. Designated ‘masters’ and their students ‘apprentices’, they were tasked to pass on their precious knowledge to the young ones in a ten-day intensive studio workshop session for each of them. Within that context, the title of the biennial, The Studio, made sense.

Matt Kayem talks about the relevance of this year’s Kampala Biennial.

The Relevance of the New Kampala Biennial

While other cities around the world with this event, the biennale, choose to show their top contemporary artists and countries fielding their best at the Venice one, it was a different case in the capital of the Pearl of Africa, Kampala. Since the city or country doesn’t have contemporary artists worth showing-off to the world according to this year’s curator, Simon Njami, he chose to introduce a system that could make the contemporary artist. For the third edition of this major event, the veteran curator and writer preferred to educate than celebrate. There is nothing to celebrate after all. So he invited seven internationally acclaimed and foreign artists to train young artists from the city. Designated ‘masters’ and their students ‘apprentices’, they were tasked to pass on their precious knowledge to the young ones in a ten-day intensive studio workshop session for each of them. The seven master artists included Adoulaye Konate, Bili Bidjocka, Godfried Donkor, Myriam Mihindou, Radenko Milak, Aidah Muluneh and Pascale Marthine Tayou. What brewed contentions on the young scene however were why there was no Ugandan in the masters’ line-up.

Guests in the lounge area of the Kampala Biennale exhibition.

Gustav Corbet on the poster.

With this kind of provocative model, this biennale has started up a would-be fruitful debate which penetrated into the emotions of local art practitioners. Some found it demeaning and selfish for the curator to ignore all that has happened in the industry and for him to try and impose or seem to create what he thinks is lacking. Matters are worsened with the fact that he is an outsider from Swiss. Regardless of him looking like one of us (he is of African descent), he comes from a place (Europe) with a history of subjugating and imposing itself on Kampala (Africa). To some, this looked like another version of colonialism with the ‘masters’ as missionaries spreading the new gospel of art because of their strong links with western nations even if most are ‘Africans’. They ridiculed the whole setting of the event from its poster which bears an 1855 painting, “The Painter’s Studio” by Gustav Courbet to the special commendation awarded to the masters as opposed to the young artists in the show. The master artist’s names where highlighted with bigger lettering at the credits of the show. One critic mentioned, “the young artists voice seemed to be silenced at the exhibition” .They asked questions like, “Why should we have outsiders dictate what art we should do?” , In the case of the poster, “Why should we still hold anything western as better than our own?”

However, I noted that some of this criticism is egotistically driven. We cannot fly as eagles without wings yet. So it’s better to we keep our featherless wings down and try them out when they have grown some feathers.

Pascale Marthine Tayou in ‘his’ studio

Away from the negatives, the fruitful debate would start with whether Kampala or Uganda at large has artists capable of transferring valuable knowledge to the younger generation in such a setting. If there is none which is most probably the case, then this biennale is intrusively calling on Ugandan artists to pull their socks up. Looking at the line-up of the master artists in the show, they have graced important platforms in the contemporary art world from Kassel, Venice and London.

Paul Nedema, The Seal of Confession, 2016

Paul Ndema was the first Ugandan artist at a major art fair in 2016 at 1:54 which has seen Ian Mwesiga, a much younger artist get shown at the prestigious event. Meaning that we are just getting introduced or initiated in the high-status club of contemporary art. So it’s crucial to note that the curator, however notorious he has presented himself to the Kampalans, he has poked the Ugandan artist to prove him wrong. For this is just a continuation of Njami’s notoriety which started two years ago with his infamous and extreme statement, “There is no contemporary art in Uganda”. The big bully has stroke and should only sit back to wait for vengeance from the small new kid in school. The sleeping scene was probably in dire need of a bucket of water splashed in its face to wake up.

Noor Okulo’s triptych from Aidah Muluneh’s studio.

Titled “The Studio”, the biennale’s goal this year revolved around the transmission of knowledge from an older generation to a younger one. This meant that the younger artists would get introduced to new and valuable ways of working and thinking. In Abdoulaye Konate’s studio where I was an apprentice, saw us go through weaving which is an old practice traceable in various civilizations around the world. I have been painting on denim, Dutch-wax print and bark cloth. So this method of working was relatively new to me. So many of my counterparts were made to forget their usual ways and dive into the new waters.

The tapestry of the writer at Konate’s studio

Ocom Adonias who I’ve known to be a traditional and figurative painter was introduced to animation in Radenko Milak’s studio. In a collaborative project between the two, they combined stop motion with frame by frame which was new to the young painter. Arim Andrew, also figurative painter was assigned to Myriam Mihindou’s studio where he got knowledge about the elusive world of performance art. In this studio, they explored freedom and control versus the body, mind and soul in two video performances and the live performance at the opening. And to this, we should be able to see a league of new practitioners working in line with international standards of the art.

Myriam Mihindou with her apprentice performing at the opening.

Also worth noting is that such an event always fosters creative and unconventional thinking which is central to the contemporary art conversation. At this biennale, locals artists were thrown out of their usual canvas, paint and white walls as the exhibition was housed in an unorthodox venue, a run-down warehouse. This allowed for works such as Gilbert Musinguzi’s ‘Invasion’ and Sandra Suubi’s ‘Ebirooto’ to be erected and comfortably interact with the space as it could readily hold them. Such works couldn’t probably have been created in the usual white cube.

Gilbert Musinguzi, Invasion.

The overall public nature of the biennale also allows art to be challenged and confronted by various groups of people. The Kampala edition had a program that invited several schools to the event. With this, the biennale builds and reaches out to a larger community which feeds into the art scene, growing it and structuring a local lot of art enthusiasts. A workshop that provided in-depth advice in investing in art was much needed and was one of the biennale programs. Local business people and others were invited to exchange ideas on the prospects of slicing part of the hot cake (African art).

Generally, the biennale tried to touch on key areas that make up the system of thriving art scene. Another workshop, this time about critical art writing was chaired by Frieze editor En Liang Khong which I also attended. Documentation of what happens is another problem slowing down the art industry in Kampala and what better way to solve it than have an experienced person like En to take the local writers into class. We went into basics of professional art writing and critiquing where we had to end with reviewing the biennale.

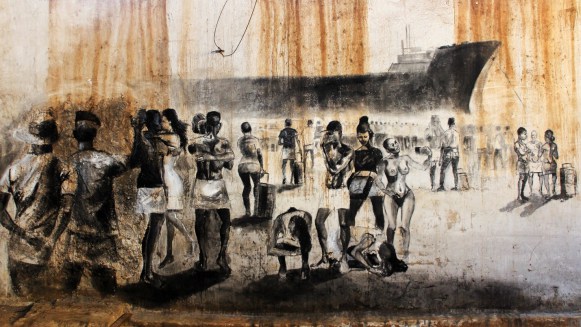

Part of Ocom Adonias’ wall drawing Doors of No Return

This event also attracted art enthusiasts from around the world. I remember meeting a lady from Ethiopia who was in the city purposely to attend the event. We could run the old cliché of them bringing in foreign exchange to the country but since the event is still young, we can’t count so much on the 300 plus who flew in for the show. What we can comfortably affirm though is that during studio visits which is another program on the biennale list, local artists and mostly those not involved in the major event got connected to the right people. This particular one, having a line-up of the big wigs of the industry surely attracted a number of ‘right’ people to the capital. This in the end has opened doors and flipped Simon Njami’s earlier controversial statement. There is contemporary art in Kampala now.

Video installation from Myriam Mihindou’s studio.

This biennale with its rather odd model should be seen as a springboard for emerging artists. This is meant to be a platform where the young voice is shaped and horned. The Director, Daudi Karungi says the event is going to run on this model for a while. If this happens, then the Kampala art scene of 2026 will have a proliferate of young creatives ready for Venice or Kassel.