Perhaps this is the most relevant discourse for black audiences today who may feel distrustful towards white media for under and misrepresenting them, but also overwhelmed by the pressures and stereotypes of what it means to be black. Just as Cheryl found a role model in Fae, perhaps people of color can also find a role model in Cheryl. There is a lesson to be taken in her fun, cheeky, open-heartedness and the way in which she learns that ownership and identity is not just a matter of birth but also a case of discovering oneself and enjoying the process.

Christabel Samuel on the relevance of the 20 year old black movie The Watermelon Woman for black audiences today.

The Watermelon Woman: A Retrospective Look at Black Issues

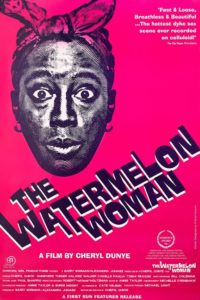

This year marks the 20th anniversary of Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman. Heralded as the first feature directed by a black lesbian, Dunye also wrote and starred in this debut. If that wasn’t already a tall order, The Watermelon Woman invites attention onto black issues that are still as relevant today as they were 20 years ago.

Cheryl Dunye (photo: Andrew Corpuz)

Shot on just $300,000 the low budget indie vibe is actually a big asset to the film. Dunye is charmingly plucky and this gutsy spirit reflects the guerrilla style of filmmaking and investigating characterised in the plot. The set-up is smart and self-conscious. Dunye plays a fictionalised version of herself; a video store clerk who moonlights as a videographer for weddings (‘urban realism’) with her friend Tamara. At work she notices that black actresses in typical 1930s ‘mammy’ roles are never credited for their work. In one film she is struck by an actress who plays The Watermelon Woman and from this moment on she decides to shoot a documentary about the mysterious woman’s life, in an attempt to commemorate the actress and in doing so document a small piece of black film history.

(Warning: The article may contain spoilers.)

Art as Activism

In a world where media and film wield such influence on our culture, battles with representation and access are still being fought. Today criticism over ‘white washing’ movies is an ongoing subject. The Watermelon Woman invites us to think about this in a more historical context and thus pulls out the heritage of this power struggle. Black people, more specifically black women, even more specifically queer black women have been kept anonymous in the archives, unaccredited and held back from accessing a culture which carries pain but also power.

Still from the mobie (copyright Dancing Girl Production).

In the films Cheryl watches, the black women are ‘mammy’ archetypes wherein they play nannies, housekeepers or domestic servants who look after the home and children. Its history, rooted in slavery, has been mythologized and sanitised to fit the white sensibilities of a faithful, desexualised matronly black woman, loyal to her white family. Usually portrayed as older and/or overweight, the mammy was not a threatening black icon like the ‘jezebel’ archetype; in fact it could be argued she was more a white concept moulded into the image of blackness.

This tradition is explained to Cheryl and Tamara by Lee Edwards, whose knowledge of Philadelphia’s black culture is a powerful reminder that knowledge is power and in seeking knowledge of the Watermelon Woman, Cheryl is seeking the power to tell a black story.

Along the way Cheryl discovers the Watermelon Woman’s real name was Fae Richards and that she too was a lesbian. This extra layer of ‘otherness’ not only resonates with Cheryl’s character but also for the real Cheryl Dunye, who originally researched black film history for queer narratives but found nothing but ‘homophobia and omission’. So we have a queer black woman, making a film about a queer black woman who is making a film about a queer black woman. Through this layering the plot echoes the struggles of seeking hidden narratives, art imitates life – life imitates arts. The journey becomes not just a black discourse for Cheryl but one of self-discovery and self-discovery is just as important today for black audiences as it was in 1997. Recently Get Out (a horror-commentary on the threats facing black men) is just as topical for the Black Lives Matter audiences as The Watermelon Woman was for politically astute audiences of the time.

Released within a period known as New Queer Cinema, Dunye’s film reflected the movement within gay and lesbian filmmakers seeking to build a culture and generate activism through film. Dunye’s character was in part an ‘everyman’ figure for contemporary black lesbians who were switched on to the causes and protests of the time. She represents the intelligent, proactive person of color embodying the spirit of the age. In the same spirit movies today like Get Out or Moonlight – which cleaned up at the Golden Globes and Oscars – are championing black narratives at a time when black lives and black rights are under threat. This is art as activism when we need it the most.

Black and White Issues

There is a scene where Cheryl is harassed by the cops who mistake her for a male ‘crack head’. It is tense, short, sharp and one might wonder if The Watermelon Woman were written today would the scene have taken a sinister twist. Police profiling, racism and brutality is nothing new and has been explored in canon of Black Cinema. The brevity of the scene here is not a protest against the injustices black people face but more a snapshot into the everyday micro aggressions they live with.

This discourse lives on today and is another theme that The Watermelon Woman carries on from its exploration of slave traditions. After all, Cheryl’s muse Fae Richards acts in a film called Plantation Memories and as we learn, the dynamic between black and white people is a huge focus in Fae and Cheryl’s stories. As Cheryl learns more about Fae she discovers that not only was she a lesbian but that she may have been involved with Martha Page, the movie’s white director. Meanwhile Cheryl develops a love interest of her own in the form of Diane, a white lady whom she meets at the video store. This annoys Tamara who out of the two is more grounded and radical in her black identity. Thus Cheryl’s project grows another later of meaning. On the surface it seeks to discover a historical black identity but as her obsession over Fae’s personal life grows, it becomes a catalyst towards understanding her own contemporary black identity.

By mirroring Fae’s alleged affair, the movie parallels the challenges between black and white relations. Historically sex between the two groups has been stigmatized as abusive or fetishizing from either party. For example male slave owners raping or coercing their female slaves into having sex was a commonly known ‘secret’ in the community. Likewise Fae’s suspected relationship with Martha would have been hidden not only because it was same-sex but also because the 1930s did not take kindly to black and white romance. Meanwhile in 1997, Cheryl’s own romance with Diane is met with resistance by Tamara who perhaps sees it as a rejection of black-black relationships. The power dynamic between Diane and Cheryl also demonstrates dominance and submission. Diane discovers that Cheryl has been renting tapes under her name and takes them from her, inviting Cheryl home to retrieve them. They end up watching the movies together in a night that ends with sex. The scene is the climax of their flirtations and is consensual but Diane’s seductive lure takes advantage of Cheryl’s lower social status as a clerk; a role that exists to serve Diane.

Tamara’s disapproval of their relationship leads her to accusing Diane of having a fetish for black people and for Cheryl wanting to be white. Tamara espouses a more rebellious black stance against the ‘mainstream’ (white) society which sees Cheryl’s bond with Diane as a betrayal of not only her social standing but her race. Herein lies the complexity of black-white relationships as presented in cinematic traditions.

The Missing Link

As Cheryl’s investigation grows towards a denouement she finds a new lead in the form of a photograph given by Fae to a woman called June Walker. Cheryl discovers that the relationship with Martha Page was a red herring; she was never Fae’s lover and after a phone call with June, it is revealed that June was Fae’s partner for 20 years. Hidden in the shadows of shame for so long June is angry at Martha and encourages Cheryl to finish her project and tell their story. Cheryl does finish her project but along the way severs her relationships with Diane and Tamara.

Still from the movie.

What conclusion can we draw from this ending? If Tamara and Diane embody two different, polarised models then Cheryl’s independence can be seen as not merely a rejection of those linear beliefs but more so the actions of an individual finding their own way through muddled narratives. Discovering Fae’s story transformed her from a ‘mammy’ and a ‘watermelon woman’ to a real person with a name, identity and fascinating hidden life. Cheryl reclaimed a black story from the forgotten archives of history but in doing so first had to surmount the obstacles from black and white communities and their limiting beliefs of who and what Cheryl must be in order to succeed.

.

Perhaps this is the most relevant discourse for black audiences today who may feel distrustful towards white media for under and misrepresenting them, but also overwhelmed by the pressures and stereotypes of what it means to be black. Just as Cheryl found a role model in Fae, perhaps people of color can also find a role model in Cheryl. There is a lesson to be taken in her fun, cheeky, open-heartedness and the way in which she learns that ownership and identity is not just a matter of birth but also a case of discovering oneself and enjoying the process.