Engaging with the historical economies of racist imagery through citation and repetition, his art shows how “visual referents circulating in different geographic and exhibitionary context generate their own image worlds,” countering the commodification or invisibility of black bodies.

Jean-Christophe Maur on Thebe Phetogo

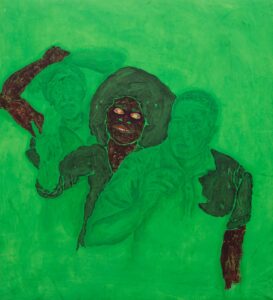

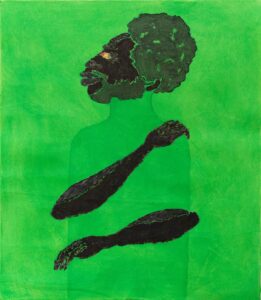

Blackbody Composite siren, 2020, courtesy Kó and the artist

(first published: November 5, 2021

Thebe Phetogo – Green is Black

Thebe Phetogo’s haunting paintings stun the viewer with their vivid green. Not one of the soft greens found in nature but mineral, chemical pigments redolent of the color of absinth and cobalt bromide. A bright artificial green, a poisonous, magic substance. A green that suffuses the paintings, challenges the eye and is a door to the invisible, the unacknowledged.

Phetogo will have his first solo show in the United States with Van Ammon Co in Washington, DC, in November, his third solo in a little more than a year, following Ka Go Lowe at Guns and Rain in Johannesburg in March and Black Body Composites at Kó in Lagos in November 2020. The artist, born in 1993 in Serowe, Botswana and currently based in Cape Town, South Africa, engages with the complex and deep tradition of Black representation in both novel and provocative ways.

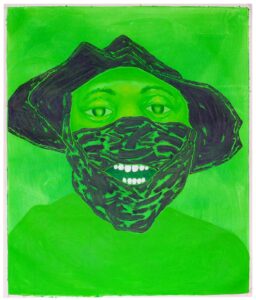

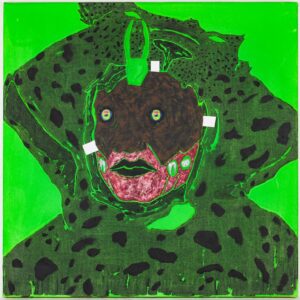

Self Portrait as a Rogue, or, the Night’s Entertainment, 2021, Courtesy Von Ammon Co and the artist

Representation

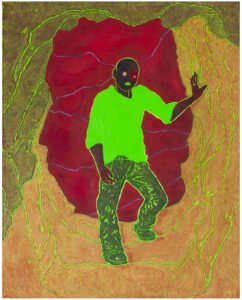

Phetogo invokes chroma keying, the visual-effects technique that employs a uniformly colored screen as background to a subject on camera, whereby allowing for a different background to be added in post-production. In theory, chroma keying can work with any background color, but green and blue are commonly used because they are most distinct from human skin tones. The green screen is preferred for live television, since people often opt for blue clothing, and it has therefore become the metonym for the technique.

Phetogo shares the green screen metaphor with another rising star, Sandra Mujinga, a Norwegian artist born in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Like Phetogo, Mujinga interrogates the fraught tradition of the representation of the black body and the invisibility of black skin. In Mujinga’s worlds, “Green is ultimately Black.”

In an interview with the poet Olamiju Fajemisin, who remarked that “people describe black as an ‘absence’ of color, an ‘absence’ of light,” Mujinga interjected that “it’s the opposite.” (1) Starting from the premise that black is the combination of all colors, the artist zeroed in on the duality that interests her and that also informs Phetogo’s practice: black is everything (all colors), but black is also emptiness depending on the (mis)perception of others. Or, in the words of the narrator of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man: “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.” (2)

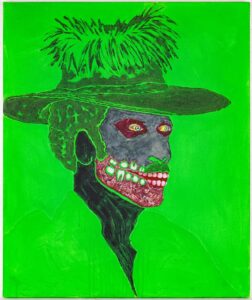

Tshetlha, with a bit of pomp, 2021, Courtesy Von Ammon Co and the artist

The green screen is a perfect vehicle for this duality crucial to black representation since it can potentially represent everything, “all colors,” but is also empty, signifying absence. The fertile metaphor of the green screen explains how two artists working in distinctly different media—Phetogo’s paintings versus Mujinga’s sculpture, video, and installations—nevertheless converge on the use of green to interrogate the (in)visibility of the black body.

While the green screen is a key metaphor, Phetogo’s paintings also draw their power from the unsettling emotions bright green pigments can convey. Especially when associated with skin tone, green is a signal of illness of the mind or body, often linked to the absorption of noxious substances. From the Impressionists’ absinth drinkers to the Blaue Reiter and Die Brücke painters to Edvard Munch, green has been associated with a break from classical painting and exploration of the margins. The disturbance created by the bright green pigment continues to be critical and generative today, as in the work of Salman Toor, for whom green is “glamorous,” “poisonous,” “intoxicating,” and “nocturnal,” creating a third space that allows new subject positions and identities to emerge. (3)

Beyond the green screen, Phetogo has also been inspired by the concept of “black body” in physics, where it refers to an ideal object that absorbs all the light that falls on it, thus becoming invisible to measuring instruments.(4) However, physics’ black bodies are theoretical constructs, not a reality: the invisibility of anybody in the universe comes down to a limitation of perception. Phetogo explores this blindness in the series of works he presented in Blackbody Composites.

Descent to Zone, 2020, Courtesy Guns and Rain and the artist

Rewriting the narrative of blackness as absence of light also connects Phetogo to an important tradition of Black representation and recalls Glenn Ligon’s account of his conception of Warm Broad Glow (2005), his first neon work. When visiting the workshop of a neighbor who was fabricating neon signs, Ligon asked whether it would be possible to produce neon letters in black. It wasn’t, he was told, because black is the absence of light. (5) Ligon proceeded to come up with a process that enabled him to create black neon letters for his work. In the words of the narrator of Ellison’s Invisible Man, explaining how he tapped a power line to light his underground living: “I’ve illuminated the blackness of my invisibility.” (6)

Invisibility

Ellison’s novel has been a key literary point of reference for many artists, beginning with Gordon Parks’ photographs for Life magazine of Ellison himself, to Faith Ringgold, David Hammons, Kerry James Marshall, and more recently Jeff Wall, Glenn Ligon, and Hank Willis Thomas to name a few major figures. It is not surprising to see their fingerprints in Phetogo’s work alongside the strong overtones of Ellison’s novel.

Blackbody as a Bodyprint (after David Hammons), 2020, Courtesy Guns and Rain and the artist

Phetogo references Marshall in one of the works for his MA thesis. Phetogo’s Portrait of a blackbody as his Material Self pays homage to Marshall’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self. Marshall questioned the invisibility of black skin through his black-on-black technique, demonstrating that the richness of the palette of blacks allows him to paint with the same freedom as any other colors.(7) Marshall himself was preceded knowingly or unknowingly by Faith Ringgold’s “Black Light Series” from 1967. Two portraits from Ringgold’s series in particular, Man and Woman, use the chromatic strategy of the black background from which the color of the skin and the face emerge through a call to attention and close looking. At the end of Invisible Man the narrator refuses to “strive toward colorlessness” and affirms that his “world has become one of infinite possibilities.” Phetogo’s answer to the black-on-black technique is to place the black body against the green screen: a negation of blackness as an absence of light, relocating it against the background of infinite possibility, and affirming painting “as a stand-in for history and the world at-large.”(8)

Minstrelsy

The black body has endured not only violence and erasure, but also attempts at abasement through gross caricature, another aspect of Black representation that Phetogo explores with vigor. This thread, too, can be traced back to Ellison: “My eyes fell upon a pair of crudely carved and polished bones, ‘knocking bones’ used to accompany music at country dances, used in black face minstrels; the flat ribs of a cow, a steer or a sheep, flat bones that gave off a sound, when struck, like heavy castanets (had he been a minstrel?).” (9)

Phetogo’s signature use of black shoe polish to paint his figures against the green screen, as well as the googly eyes and exaggerated white teeth of their disturbing smiles, signal another troubling tradition of black representation, blackface. A work like Portrait of a blackbody as his Material Self engages directly with blackface—yet disrupts its meaning given that the Motswana artist is interrogating the tradition from the space of the African continent. As Phetogo notes, minstrelsy as practiced in some countries in Africa did not carry a derogatory meaning. Black American minstrel artists came to Ghana and Nigeria in the 1920s, inspiring the Concert Parties form of theater. (10) The rich web of references in Phetogo’s paintings thus both place him in dialogue with the tradition of questioning and reinventing the canon of Black representation, while affirming the multiplicity of black artists’ geographical, cultural, and subject positions and confronting viewers with their racist prejudices and histories.

Roy, 2021, Courtesy Von Ammon Co and the artist

The green and the minstrel-like characters (bright green, googly eyes, carnivalesque attire) are strongly reminiscent of the paintings of James Ensor (The Intrigue, The Strange Masks). In the crowd of Ensor’s Christ Entry Into Brussels in 1889 one sees two characters in blackface in the background. There are also references to Congo masks in the painting.(11) Ensor draws on the grotesque aspect of masks to offer a satire of social convention, also drawing from the traditions of carnival of the Low Countries, where blackface characters (Zwarte Piet) had been part of Saint Nicholas celebrations since the middle of the nineteenth century. (12)

If the uncanny is a return of the repressed, then Phetogo invites us to refamiliarize ourselves with the tired and violent stereotypes of Black representation, as if to exorcize them. Engaging with the historical economies of racist imagery through citation and repetition, his art shows how “visual referents circulating in different geographic and exhibitionary context generate their own image worlds,” (13) countering the commodification or invisibility of black bodies.

Phetogo plays with multiple registers that lend his works their strong evocative power. His richly layered practice invites inquiry and reflection, while his keen awareness of historical context opens up cultural and historiographical depths of meaning.