Spontaneity is a word that rings in Waswad’s head as he sets out to work on a piece of artwork. He says he doesn’t sketch or plan for the work and therefore works with his initial idea which he continues developing as the work progresses. He says he prefers to work with the raw idea, unhampered by rigorous planning and sketching which ends up destroying its originality.

Matt Kayem about the work of the Ugandan artist Waswad

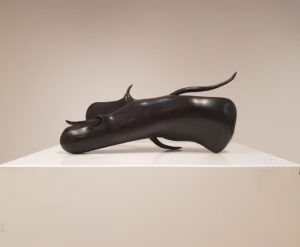

Waswad’s Amasendela, albizia and ebony wood, 87 x 30 x 40cm. Photo by the artist.

Waswad on the future of man

Artificial intelligence, science, technology and environmentalism are some of the themes that spring-up after a thorough engagement with Waswad’s new body of work entitled Degenerative Evolution of the Living. For you to pick up on these themes and much more, you need to be in Johannesburg, at the Absa gallery from 25th March to 20th April 2018. The show is one of the rewards of Waswad being the second runner up at the Barclays L’atelier Award in 2016. The prize is the most prestigious contemporary art award on the African continent aiming at uplifting the careers of young African artists. It is a tremendous opportunity for the Ugandan artist who is showing for the first time in South Africa to a bigger and more international audience. And on the other hand, a wonderful prospect for Absa gallery to show an artist who makes the cream of contemporary art in Uganda.

Tengere, albizia and ebony wood, 66 x 34 x 31cm, 2017. One of the sculptures on display. Photo by the artist.

You’re bound to miss the intended narrative around the art because of the employment of natural organic materials to addressing themes to do with technology. This is an unexpected spin-off as you would relate machines to artificial substances like metals not leather or wood. But as they say, an artist makes us see with a brand new pair of eyes and this is what Waswad does as he juxtaposes concept and media in this spectacle. To this, the artist says he loves the ambiguity that comes with this but also the issue of the show targeting the future man, a being who will walk into a museum to interact with the then extinct and precious artworks of albizia and ebony wood. The wood would most probably be extinct by then. Well-polished wooden sculptures, ink on paper drawings and leather-tailored installations blend well with the laminated floor and white walls of the gallery fetching the much needed plus on presentation and aesthetics. There are over 20 artworks that have been done between 2017 and 2018.

Give us this day our daily bread, on display at the Absa gallery. Photo from the artist.

Waswad has been known to push boundaries in his art and he doesn’t forget that in this collection with his signature appropriation ideas of the found object as witnessed in the sculpture, Give us this day our daily bread. Three different types of corn in jars are paraded to the future beings (his desired audience). They scream, this is what humans ate! He says he bought the three different types of corn at different prices which hints at GMOs. Are GMOs a threat to our existence? he seems to ask. I highly think so and interestingly had someone who thinks otherwise which sparked off a debate amongst us. If a scientist tweaked the DNA of a tomato and added strands from haemoglobin of the blood of say; a cow!! Would you wanna eat that tomato? Don’t you think there would be repercussions to face for such games? Well, he leaves the conversation to you. Wise Enough is another installation comprising of creased paper hang in framed glass where he continues to blur the boundaries. He says the two bizarre installations are partly inspired by Lamb’s lyrics, an English electronic music duo.

Part of the installation, Wise Enough, at the Absa gallery. Photo by the artist.

Remixed by Waswad, the lyrics appear in the catalogue as an entry to the installation.

I had a dream that all of time was running dry

And life was like a comet falling from the sky

I woke so frightened in the dawning, oh so clear

How precious is the time we have here

Are we not wise enough to give all we are?

Surely we’re bright enough to outshine the stars

The human kind gets so lost in finding its way

But we have a chance to make a difference till our dying day

And you might pray to God, or say it’s Destiny

But I think we are just hiding all that we can be

Are we not wise enough to give all we are?

Surely we’re bright enough to outshine the stars

The human kind gets so lost in finding its way

But we have a chance to make a difference till our dying day

All I’m really asking is: what are we doing here?

Are we just killing time? Just living year to year?

In this big world, no one else can play our part

Ain’t it time to just wake up and give it all

Are we not wise enough to give all we are?

Surely we’re bright enough to outshine the stars

The human kind gets so lost, and in finding its way

We have a chance to make a difference till our dying day

We have a chance to make a difference till our dying day

We have a chance to make a difference till our dying day

For a while now, the artist has been interested in how humans are affecting the environment and vice versa in the face of time, as seen in his two previous shows, Zikunta and To Live Is To Become. He has continued in the same line of thought with this body and dived much deeper this time as he continues to encourage conversations about identity and belonging. With Darwin’s theory of natural selection in mind, he imagines a future, possibly 500 years from now where humans have been enslaved and over-powered by new beings which evolved from them. In the gallery, the alien-like sculpture representations grace the top of white pedestals, warning us of the beauty and danger ahead which you and I will never see. He not only imagines but also fashions a whole narrative rooted in science and facts which goes;

At some point on the evolution continuum, as the species kept tweaking their DNA for better progeny, something “went awry” and highly developed life forms were created unexpectedly. They became the predecessors of the first known “humans”. The intellect of the new life forms was so advanced that soon they overrun their “creators”.

*

Because of the elevated intelligence of the new life forms, they started ruling over the now “lower” life forms that created them. They subjugated them and gave them new nouns—dogs, cows, horses, etc., while they called themselves “humans”. The superior intelligence of the humans enabled them to make many discoveries and advance rapidly. But biological evolution never kept pace with these changes and the humans, unable to observe any significant evolutionary change in their physiological and biological makeup, decided to take matters in their own hands. They started to tweak their DNA and improve on themselves and cloning was born. In secret labs firmly hidden from view and guarded by layer upon layer of impenetrable security, the ethical boundaries of cloning were pushed to their very limits. Unable to keep pace with the vast and often ominous possibilities of cloning, humans became obsessed with amplifying their intelligence with artificial intelligence.

*

The quest for artificial intelligence became so advanced and so obsessive that before long, self-propagating super-intelligent humanoids became a common site. They possessed emotion and could choose to be benevolent or malevolent to humans. They eventually overrun and took control of the humans who “created” them. Humans inadvertently became “manimals”. They were subjugated by the humanoids they created to “improve” on themselves so as to maintain the evolution curve. To exercise full control, the humanoids started tweaking the manimals’ DNA to create variations of them, some walking on twos, some on fours, some on one, some with tails, some looking like plants, and some covered with feathers. The humanoids gave the manimals new nouns like Myaayu, Ndopyo, Ntonzi, Amasendela and the like. They caged them and used them for work, leisure, food and as laboratory specimens. Once on top of the food chain, the humans had now devolved to become subjects of the humanoids they created, becoming “transhumans”

*

Waswad’s narratives are not complete without invented words and language borrowed from both English and Luganda, a widely spoken language in Uganda. Words like Tengerere, the title of one of his works which is linked to balancing. Ntonzi, a word close to the Luganda equivalent; to create. Eyebitanga which is Luganda, loosely meaning ‘the one with spots’. It’s a word usually applied to animals. Manimals, from animals, in his story standing for the degenerated species of humans after they have been subjugated by the super-intelligent humanoids they created.

Eyebitanga, leather off-cuts and goss thread, 2018. Photo from the artist.

The oxymoron, Degenerative Evolution which is part of the title, paints a picture of rising and falling or decline and development. So the questions can fly in; is technological advancement a good or bad thing? Are we destroying our environment? Who are our successors? Are machines going to take over us? Unfortunately yes. AI poses an existential threat to humans! Evolution, by its nature only begets better species and if we have degraded our environment, cannot bear food from it, how do we expect to survive? If we have made our selves dependent on technology and our lives fast, how can we compete with the machines we have created who are on all levels much more efficient? So simply put, we are designing a world we can’t cope with, we are preparing for our successors.

*

The current fascination and advent of sex dolls makes this nightmare a reality. If we are going to make beings to replace human intimacy, what does that say about natural procreation? Where does this leave the family unit? All this leaves the future of humanity in jeopardy. Manufacturers of these toys will compete to producing the closest thing to humans ending up crafting intelligent and emotional beings that are self-reliant, aware of their environment and rights. And these beings standing up for themselves in face of abuse and violation as it has been portrayed in the T.V series Humans and the 2014 science fiction thriller film, Ex-Machina. The thesis that AI poses an existential risk, and that this risk is in need of much more attention than it currently commands, has been endorsed by many figures; perhaps the most famous are Elon Musk, Bill Gates, and Stephen Hawking. This calls for a little sigh of relief to the artist and others, knowing that they are not alone in the nightmare.

Ndopyo, a sculpture in the series on display carved out of ebony wood. Photo by the artist.

Afrofuturism, a hot topic and movement comes into thought after engaging with Waswad’s work. How? Why? The fact that the artist is African and his work being futuristic should just be enough to connect the two. The aesthetic quality in his work and his confrontation of technology, a subject with an obscure linkage to Africans conjures up ideas of alienation, all which is associated to the movement. There is no doubt that Waswad’s extra-terrestrial beings would marry well in a group show with names like Osbourne Macharia, Cyrus Kabiru, Eddy Kamuanga and Wangechi Mutu because of the shared school of thought.

Day 5 at the MNA station, ink on paper, a drawing on display at the gallery. Photo by the artist.

Spontaneity is a word that rings in Waswad’s head as he sets out to work on a piece of artwork. He says he doesn’t sketch or plan for the work and therefore works with his initial idea which he continues developing as the work progresses. He says he prefers to work with the raw idea, unhampered by rigorous planning and sketching which ends up destroying its originality. Think of the abstract expressive canvases of Jackson Pollock and the automatism ideas of the surrealists. While the latter took it to the extreme, making creative expression not to be governed by even the artist, Waswad tries to reach for an equilibrium, letting his craftsmanship guide his ideas. Indeed, it can’t get more dexterous than this when you have a multitude of processes like sewing, carving, sanding and draughtmanship all expressed in one body of work. For the drawings in ink, they could look child-like from a far but on a closer eye, they look so meticulously done, almost as if printed from printer.