As other artists and scholars have targeted ethnographical museums effectively, questioning their colonial heritage, Nazareth adds elements of his personal history to the discourse. While loosely knitting together elements and fragments of histories and his own adventures, Nazareth’s actions evoke a sense of a search for fairness. It seems as if loops and holes exist, little pockets of time and space in between his performances, his writing, in the way he talks his mix of languages, his broken English, that provide room for interpretation and for engagement.

Machteld Leij on Paulo Nazareth.

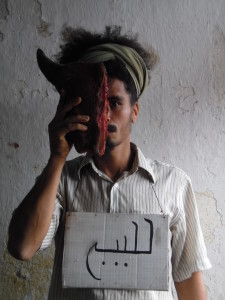

Untitled (from the Para Venda [for sale] series), 2011.

Paulo Nazareth

SENSE OF URGENCY

Slowly the rented black car with tinted windows creeps up the hill of Favela Veneza, near Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Darkness has already set in, not the best of times to visit any favela, but our goal is too important: Paulo Nazareth’s ‘Biennial do Veneza’, his personal biennial on top of the largest hill in Veneza. Nazareth gives directions to the driver. The director of his gallery and two art critics visiting from The Netherlands, accompany him.

Untitled (from Noticias de America [News from the Americas] series), 2011/2012.

As we arrive, we are greeted by a man with a huge gun, idling. He seems to guard the surroundings. Drug traffic related, probably. But he’s friendly enough, though, as he spots Nazareth small boyish figure, bare feet in slippers, big Afro hairdo and his identity card around his neck. The authorities never seem to get enough of asking him to identify himself. The artist, who travelled on foot from Brazil to the United States as a performance, is not at all impressed by the weapon. Nazareth is one of those people that have their own type of energy flow around them, shifting between quirkiness and geniality. Renato Silva, director at the gallery Mendes Woods in Sao Paulo represents all the ‘bad guys’ of the gallery, the political activists, and the artists that march to their own beat. He believes Nazareth to be somewhere between Bob Marley and Mahatma Ghandi.

Nazareth opens the door to the rather derelict favela house. Inside are small works of art by him and by friends. Also a heart of textile and rope, made by Sonia Gomes, a Brazilian artist we met earlier today. Her tactile work, meant to touch and feel, to engage with, was shown in this year’s Biennial of Venice, as well as here. The one in the favela is a gift, to Nazareth’s new-born daughter.

Untitled (from Noticias de America [New from the Americas] series), 2012.

Nazareth (1977, Governador Valadares) participated in the Biennale of Venice in 2013, in the garden of the Arsenale with an installation of foods and goods and two indigenous men who talked about their lives with the audience. In 2015, he has contributed to a sound installation of indigenous languages on the verge of extinction, shown in the Latin American pavilion. He exhibits quite regularly in Europe, recently in the Lyon Biennale, and in Oslo for instance. Still the continent hasn’t had the opportunity to greet him personally, as he plans to walk the earth of Latin America and Africa, before going to Europe. He’ll get there eventually, finding his way via Africa. It is not a matter of dislike of Europe, Silva tells me, it is just a matter of priority, as Nazareth wants to understand his own roots first. In 2011 Nazareth went by foot to attend Art Basel Miami Beach. His trip took him almost a year. He was met with disbelief by border patrol; sometimes they didn’t accept his passport. He was wearing flip-flops, not washing his feet so they gathered the dust of all the America’s, to be washed off in the river Hudson as an apotheosis of his journey. While travelling, he took pictures of himself and the indigenous people he met during his travels, to look for similarities, to look for differences (‘Noticias de Americas’, 2011). It is his own background, being of African, Krenak and Italian descent that fuels his search for identity. Sometimes people think he is black, either indigenous. In Cuba, he was perceived as local. On Facebook he posted a message: “Being mixed-race and travelling through the Americas, my skin changes every day. At home the labels are not so well defined…I cannot open my mouth because then my skin color changes, there are days when I am an Arab, Pakistani, indigenous and other adjectives which may change according to other people’s gazes and the words to come out of my mouth at any rate, sometimes in the United States of America, when I go into white people’s shops, everyone is afraid, including me.”

Banana Market/Art Marquet, 2011.

At Art Basel Miami Beach he sold bananas from a Volkswagen microbus, ten dollars apiece. He gave them away, to cleaners for instance. A woman visiting the art fair was on the verge of getting arrested for damaging a work of art as she took offence when she saw the artist donating them while others had to pay. As a reaction, she tried to steal a banana. All eventually was hushed. Nazareth’s ‘Banana Market/Art Market’ (2011) meant to address the strange mechanisms of the art market, and this incident accidentally supported his performance.

Let’s go back to Nazareth’s own ‘Biennial de Veneza’, organised by the artist for the second time. It is of a different order than its European counterpart. In such a faraway place, it is meant for the inhabitants of Veneza, as a means of transposing art that would normally not be part of daily life in the favela. Plans are made with the gallery to visit the favela-biennial with students, to enhance the chances of an encounter between groups of inhabitants that normally wouldn’t meet. In the corner Nazareth laid out little objects, the feather of an Angolan bird is dancing through the air. It is from a bird that made such a noise, it could easily cloak the sounds of runaway slaves in hiding, explains Nazareth. In Africa the bird is extinct, it still lives in Brazil.

L’Arbre d’Oublier [Oblivion Tree], 2013, video still.

Nazareth directs us further up the hill behind the small house. It’s rather steep. Nazareth climbs up and reaches out to pull everyone of our company up the mould. Up a bit, through a field of long plants until we reach the top. The artist’s points out the routes in the valley below, how the winnings by colonialists travelled through the land, to the coast to be shipped to Europe. It is not the first stop we made, for Nazareth wants to show how gold and sugar was transported through the landscape and thus forming the colonial history of the land. As he stands there, he tells us of his plans to plant a Baobab, a gigantic African tree, as a symbol for the connection between Brazil and the African continent. For Nazareth, Africa and Brazil are the same, not only through colonialism, also through the fact that the oldest human fossil was found near his home in Santa Lucia. It was the prehistoric remains of a black woman, who was baptised Lucy. So Africa and Brazil have the same DNA for a long time.

Produtos de genocidio [product of the genocide], 2013.

Earlier that day we visited the house of his family in favela Palmital, in Santa Lucia. His mother, brothers and sisters live there. Its small living room is filled with books. Land maps are produced there, and Nazareth lectures. Not only about where gold was mined, but also on how the war between Brazil and Paraguay in 1870 was fought. He tells of the urban development of Brasilia, and explains how builders were homeless after they’ve worked for Niemeyers enormous project in the jungle, how they were forced to built their own homes in favelas like his. He calls them satellite cities, not wanted in the heart of cities, as they are not considered modern. “It’s not progress”, he explains. All day long he carries two plant roots with him, from the favela plant, sharing its name with the shantytown. “First the root has to sprout, make more roots and then branches will form”, he says. To him this means he wants to visit Africa and the Americas first, as this is where his roots lie. Eventually he will go to Europe, but only via Africa, as his route is the opposite of the routes colonialism took. And why on foot? Well it is the mode of transportation of his people, the indigenous Krenak. He allows himself to always use aides, like a walking stick, or a car, like today. He flexes his feet: “as a child I couldn’t walk proper, so I practiced and practiced; now all is well.”

Untitled, 2011/2012.

He shows us the press he uses to make offset prints of food packaging, referring to Indian people, who died as a result of colonisation, flu or were murdered by the hands of the state or by land owners. That still happens today. It is genocide, explains Nazareth. He stalls out a bottle of cleaning alcohol. The label wears the name of an Indigenous people: Tupi. Nazareth hunts for the remains of slavery, for all to see, in a nutshell, in such mundane objects. Also Indigenous tribes, out of sight and marginalized, nowadays provide names for football clubs and foods. Nazareth appropriates them in his prints for the series ‘Genocide in Americas’. He also prints leaflets, giveaways as he calls them, full of facts on colonial history or anything related. He sells them down the hill, on the central square where he exploits a booth from time to time, for a real. We can buy prints too, if we want to. For us, visitors that are part of the art world, the price is not that low. Yes, you should buy something, encourages Silva, his gallerist, us. All the money he earns selling these prints goes into a local football club for children, anyway.

Mocioios, (from Cara de Indio series), 2015.

Historical, recent and personal events are entwined in Nazareth’s art. And it’s this personal aspect that makes the biggest impression. His grandmother Nazareth Cassiano do Jesus was confined to a mental hospital in the forties. Little was necessary for indigenous people to be locked up, states the artist. The fact that his grandmother practiced the religion of Candomblé, linked to the Yoruba in Africa, was enough. Many people died in Psychiatric Hospital Barbacena City. After 1963 nothing ever was heard from his grandmother again. The bodies of the patients were shipped out, sold to universities for educational purpose. He unearthed the history of human remains in the collection of the Crime Museum of Salvador City, where the heads of indigenous people are stored. ln his booklet ‘The Right to Funeral’, which he presented in his exhibition ‘Genocide in Americas’ at Gallery Meyer-Riegger in Berlin, last summer, he describes not only his findings, but also his performance in which he lays next to skulls, trying thus to comfort their spirits and claiming the right for a proper, respectful burial.

Grave and problematic inheritances shape both the man, and his work. The entanglement between the personal and the historical delivers a powerful body of art. As other artists and scholars have targeted ethnographical museums effectively, questioning their colonial heritage, Nazareth adds elements of his personal history to the discourse. While loosely knitting together elements and fragments of histories and his own adventures, Nazareth’s actions evoke a sense of a search for fairness. It seems as if loops and holes exist, little pockets of time and space in between his performances, his writing, in the way he talks his mix of languages, his broken English that provide room for interpretation and for engagement.

Black Power (from Afro Comb series), 2015.

A younger generation Brazilian artists tries to measure the past, and seeks for a way to try and understand the world of today, perhaps even change it. For instance, artist Jonathas de Andrade gets his inspiration, from the life and hardships of the Man of the North East. He made his own version of the somewhat outdated museum in Recife with the same name. The artist studies and extrapolates findings on typologies of the hard working, dark skinned man, always the outsider. It is a way of showing how stereotypes function as a means to pinpoint The Other. De Andrade also produced a manual on how to make sugar candy, a series of prints called ‘40 nego bom é um real’, (40 black candies for one real, as the popular sweets are advertised in Brazil). ‘Nego bom’ translates as ‘Good Black’. It looks plain educational, but something else is going on as it sensualises labour and the black man. In such a way that it undermines the shallow layer of innocence of the work. Subtle and suggestive at the same time, De Andrade probes the impact of centuries of slavery on the society of today. Both De Andrade and Nazareth tackle issues of racism, considering history and, in the case of Nazareth, the personal too.

So personal hardship and historical hardship are counterparts, in the way Nazareth perceives the world. The knowledge he collects form vast stories, mythologies embedded in a painful history of Diaspora, exclusion and exploitation. The performances and actions of Nazareth have a sense of urgency. At the same time, there is something ever so exiting and adventurous about his walks over the continents for instance. Nazareth’s work stings and confronts, while being elusive from time to time. It proves to be a powerful combination.

1. Paulo Nazareth, Arte Contemporânea LTDA, Janaina Melo et.al. Rio de Janeiro, Cobogó, 2012.

Machteld Leij is an art historian from Leiden. She works as an independent writer and critic. She publishes in several magazines in and outside of The Netherlands.