“As a young black female person I feel that my reality and history always call for me to transcend my experiences of being black in an anti-black and anti-woman world. The call for reconciliation in South Africa asks me to transcend my growing up in the township and the violence that comes with that.”

Manon Braat in conversation with the South-African artist Khanyisile Mbongwa.

A conversation with Khanyisile Mbongwa

We’ve agreed to meet at Haas, a hip spot at Buitenkant Street in Cape Town that functions both as coffee shop and art gallery. I have a hard time recognizing her because the long black tresses Khanyisile Mbongwa (1984, Cape Town) had the last time I saw her, made way for super short white curly hair. The elegantly shaped vintage glasses on her nose are also new.

She needs coffee and something to eat first – she just rushed down here from her studio around the corner where she had another interview, about a puppetry project called Slyza Tsotsi that will be part of the Cape Town Carnival 2016.

Apart from curating exhibitions, Khanyisile works as a performative installation artist, mostly using the body, photography and video. She never went to art school but she grew up dancing ekasi (township slang) and performing poetry for as long as she can remember, just never called it art. Already at an early age she gave workshops for writing and poetry in her home. Her professional practice evolved naturally from that. And it’s always been about finding creative ways of communicating with people, engaging with her surroundings and telling her story.

In her work ‘Iindonga’ (2014) she uses poetry and performance to address the struggle of young black South Africans to shape their identity in a post-apartheid South Africa. In the piece three young people, Khanyisile being one of them, are surrounded by historical walls of oppression, concrete monuments that serve as reminders of the past but at the same time symbols of the socio-economic and cultural walls that most black people still experience in South Africa today.

Before she did an Honor in Curatorship program at the University of Cape Town she studied Sociology at the University of Stellenbosch. She’s interested in how society develops through creative actions. Art, she says, has a part to play in redressing the present issues of poverty, racism and inequality that South Africans as a society have failed to deal with. Both her art works and her exhibitions mainly deal with the socio-economic and political conditions of race, gender, sexuality and geographical location. In her case that means being black, female and coming from a township. She moved to the city not too long ago, but grew up in Gugulethu, in Xhosa meaning ‘our pride’. ‘Gugs’ as she calls it, is a township on the Cape Flats situated 15 kilometers south-east of Cape Town.

The township and the commodification of township blackness in the tourist industry was the subject of Demonstrations: Performing Being Black, a two-part exhibition Khanyisile curated in 2013. A photographic exhibition in Gallery Brundyn showed works of photographers who had all been tasked to produce one ‘authentic image of the township blackness’. The second part of the exhibition mimicked ‘township tours’ as a critique of them and consisted of a series of performances in selected alleyways in Gugulethu where the audience could view and experience ‘authentic township blackness’.

In her early thirties now, she decided to go back to university and do her Masters in Interdisciplinary, Live and Public Art and Public Spheres at the Gordon Institute for Performing and Creative Arts, also part of the University of Cape Town.

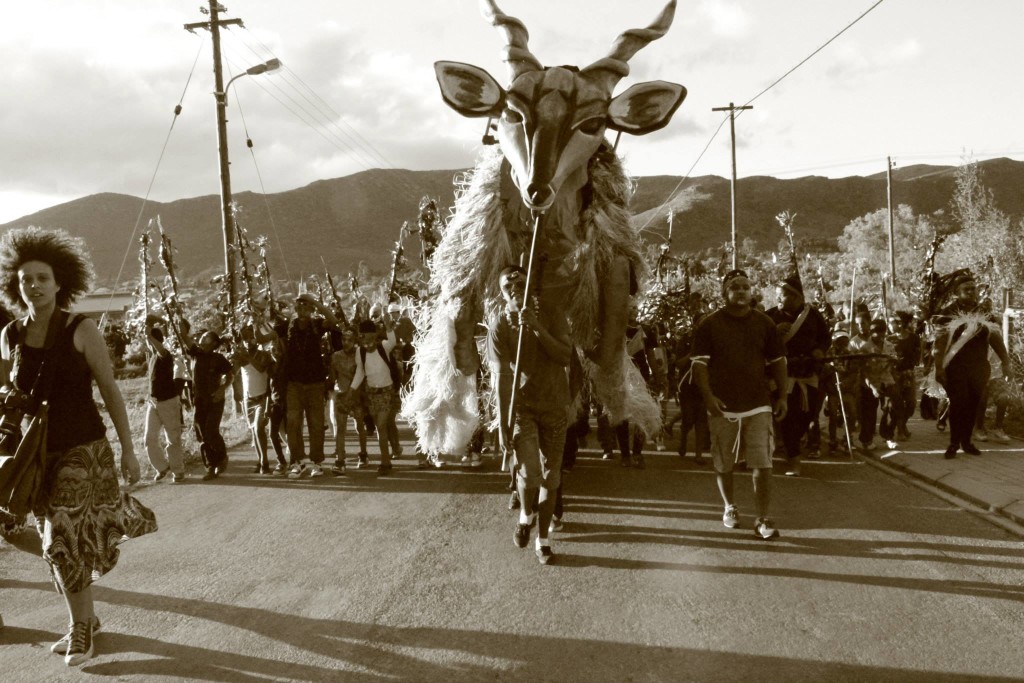

But these days she’s mostly busy working for the Handspring Trust for Puppetry Arts, of which she’s been appointed executive director little over a year ago. Only two weeks to go until its 12 March, the day of the Cape Town Carnival, and Khanyisile’s building a giant puppet that will be part of the procession through the city center streets.

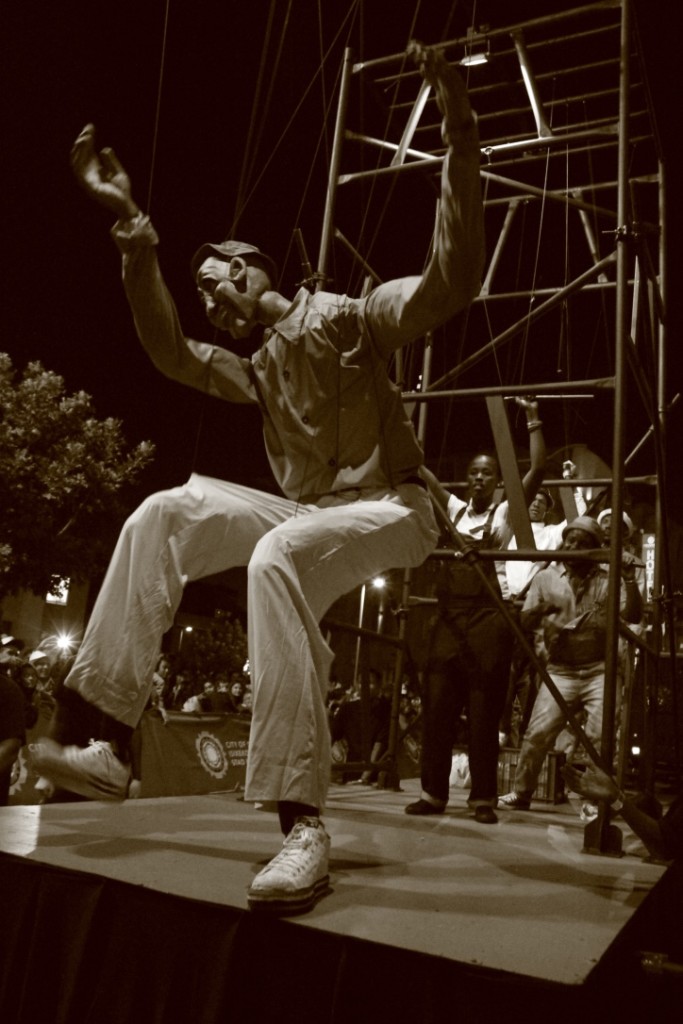

“This year’s overall theme of the carnival is Street Life. It is a concept that is relevant to the city and to the history of South Africa, highlighting how every member of our society should have a street that they can call home within our eclectic city. The puppet that we built (together with UKWANDA Puppet and Design Collective) for it is called “Slyza Tsotsi”, which is very rooted in township culture and deals with the way in which townships are built and its inhabitants negotiate the space. The term Slyza Tsotsi was made incredibly popular last year by hip hop duo Major League. Slyza means to escape, to find a different route. The township is built with all these small passageways where you can easily get trapped. Tsotsi, a slang word common to most Southern African languages, mostly refers to ‘gangster’ but it can also mean ‘street wise’. So the Slyza Tsotsi character knows his environment and how to navigate through it, he knows the in and out and is constantly aware of his environment and himself. The puppet dances the Patsula, loosely translated waddling like a duck in the isiZulu language, a dance style that quickly evolved into a lifestyle and that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s as a response to the forced removals of non-white people from their land and homes. In the post-94 context Slyza Tsotsi tells the narrative of black township life, the violence that comes with it and the ways in which we find an escape by constantly negotiating our environment. Slyza Tsotsi brings into question the historical legacy of public space in Cape Town and how the black body is seen in such spaces.

I am one of those people who left. Because I was raised by my grandmother and she worked as a nurse in Sea Point in the city of Cape Town, I was brought to school there. From a very young age I was exposed to the architectural and spatial differences between the city where white people lived and the township where we lived. And I had to manoeuver through these different worlds for a long time, experiencing this duality of being that exists.

Apartheid, by creating townships through Group Areas Act, ensured a system of structural oppression that persists as a historical legacy – that continues to serve the “center” from the margins. In many ways I didn’t get stuck in that spatial reality but I am inherently connected to it. But I can’t say I strategically planned to get out of the township that I got out because of something smart that I did. I got out because I knew something was not right even though then I could not articulate it. Sometimes you just see a crack and slip through. The Slyza Tsotsi puppet for me symbolizes the reconfiguration, the transition of the black body; finding the small narrow openings of the township and squeezing yourself a way out.”

To Khanyisile the puppets are extensions of who we are. They are life size or even bigger, giant, human looking puppets. The idea is to create a puppet that embodies a person and then manipulate it so it can transcend human’s physical, psychological and emotional limitations.

“As a young black female person I feel that my reality and history always call for me to transcend my experiences of being black in an anti-black and anti-woman world. The call for reconciliation in South Africa asks me to transcend my growing up in the township and the violence that comes with that. It’s a daily strain to transcend all that and just function, communicate and be, when our pain is not acknowledged and legitimized at home and in the world – I am always told to get over it. Some days I fail the transcending, and feel angry and depressed because I’m black and what that means in the world. I wasn’t born black, but my experiences in the world have made me black and continue to remind me what that is.”

Puppetry creates the opportunity for the manipulator of the puppet, and the audience, to go somewhere where they normally can’t, to an imagined future, a place beyond the current reality.

“I’ve been working on a puppetry project around the Reconciliation project, the project was is in its 6th year last year, in which we try to reach that imagined, better place. Many things weren’t dealt with by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. (1) That’s something a lot of people are still struggling with. After all the atrocities and blood shedding, it was too quick to talk about reconciliation, when no healing had taken place. The choice for a peaceful reconciliation came from fear of civil war; hence TRC was essentially about pardoning. But this is not justice, injustice continued to be violently exercised on black bodies. Whites were forgiven and whiteness remained privileged to a large extent, whereas no system was put into place to deal with blacks afterwards, and help them with post-traumatic stress. They had and still have to figure things out on their own. In the project we try to do exactly that, and visualize better options for the future. But it’s difficult for artists to create a work like that in the situation we are in now.”

Khanyisile states that she lives in two South Africa’s. The official one that you can see in the catalogues, with the beautiful scenery, the wild life, the great food. And then there’s the real South Africa. People have been existing in these two places for a very long time. The divide, according to Khanyisile, is only becoming more visible now because the real South Africa is running out of patience. The level of tolerance is breaking because democracy has failed the country. After 22 years things have not shifted and black anger is growing. But of course, black people demanding equal chances and fighting white privilege is nothing new, she stresses.

“I’ve been brought up in the township and I was active in the ANC youth movement and these discussions have always taken place, amongst all groups of black people. The fact that domestic workers and miners are protesting against low wages and bad working conditions and that students are fighting for the right to be properly educated didn’t come out of nowhere all of a sudden. The radical changes that were needed and promised after the abolition of apartheid to a large extend didn’t happen. But what we see now is white privileged people telling us ‘to get over it’’, that apartheid is over and that we should make a future for ourselves. Yet the reality is that the majority of the black people still lives under extremely poor conditions and don’t have the opportunity for social mobility. There’s too much backlog. So most people cannot ‘get over it’ because they are still living the aftermath of apartheid.

As we blacks are dealing with the disadvantages and are trying to work through it, white people also need to deal with their advantages, so we can create a level playing field. People talk a lot about displacement and dispossession, but no one is talking about the other side. It didn’t just happen that people were displaced and dispossessed of their land. Why is this conversation taking place only on one side and are people on the other side not engaging and talking about the privileges that are still maintained by the system? White people admitting that they’re privileged is not enough. It’s the responsibility of the government and the white people together, to bring about the necessary changes.”

Because she’s a student herself again, she engages with the student protests, the #FeesMustFall and #RhodesMustFall campaigns that are going on all through the country for the past months and demand equal chances to study at universities and ending institutional racism. Black South Africans have a history of Bantu education (2), most parents are not educated. The students want the opportunity for all the young people in the country to be educated. Khanyisile refers to the Freedom Charter in this respect that says that all shall get education. (3) The government and the institutions of education should make sure that they have the necessary means to insure that everybody will be educated. Reality is that there are only few scholarships available and that going to university is much too expensive for most black South Africans.

Khanyisile is convinced that it’s possible for the government and the universities to find a solution and that students should continue to protest until their demands are met. Her own activism in the protests is of a specific nature, and happens within the group. Khanyisile strongly advocates self-love and the conviction that revolution needs to happen without any more black bodies dying.

“So far the protests have been relatively peaceful; violence has been exerted only against structures that remind black people of the oppression from the colonial and apartheid regimes, such as paintings and statues of white colonial rulers. But every time they protest, the police uses fierce violence against the black students. It seems only a matter of time before blood will be spilt.

The only form of revolution, at least from my perspective, is self-love. Politics have failed us, the economy has failed us. We need to love the thing we were taught how to hate. Only if we start loving ourselves enough, can we start negotiating shifts. That’s the first radical step. I believe that is what’s really happening now. Black people in the world are activating that aspect, loving themselves. The Black Lives Matter movement in the Unites States is an example. Black men and woman are being innocently killed by white police officers, in that first world country that we look up to, the country that’s a symbol for democracy, opportunity, chances and freedom, the land of the abolition of slavery – it seems Jim Crow is back. When the US is exerting that amount of violence against black bodies in various ways, then we are reminded again that this world is anti-black. It makes us South Africans even think deeper about the myth of democracy in our country. Awareness of the unequal situation has been there, what’s happening now is the activism of that awareness. When you feel that the existing situation is fundamentally wrong then you want things to change and you will start acting on it.”

When she was young Khanyisile’s idea of revolution was to get everyone out of the townships as soon as possible. Now she feels this is something that people should want for themselves. It can only happen if they believe that they’re not stuck there, just because the system is built to make them think that this geographical location is who they are and where they belong. Self-love, Khanyisile is convinced, compels you to try to image beyond this reality. Even if you don’t get to see the future that you’re imaging, those that come after you can.

The township will continue to play a very important role in Khanyisile’s life and practice. Her mother, sister and son still live in Gugulethu. She still feels strongly connected to this place of her youth that was beautiful and extremely violent at the same time. She’s trying to understand the space of the township as someone who lived in it and doesn’t live in it anymore but still has strong ties. Her masters research is looking at township alleyways, the irhanga, as ways to engage with the black psyche and identity – finding other ways to engage with who we are as black people who emerge from such spaces that were designed to keep us static, docile and locked in structural oppression.

“When I was writing my Honors I was really struggling because I wanted to write a paper that my friends who I grew up with could understand. If I walked away from my studies with one thing it is the knowledge that there is no universal blackness. That was quite hard to take in. But where all black people in the world meet is that we are displaced and dispossessed of land – there is nowhere to go. I want to write about that, to understand myself better. But I am still figuring out what my study will mean in the world. And what it will mean for the people who grew up with me. Because essentially I am writing about us.”

khanyisilembongwa.com