A writer clears his path through incessant questioning—seeking more than anything else an honest evaluation of his position and place in the subject’s affairs. Devoid of any irrelevancy and unpretentiousness, a piece of writing will consequently function as honest, and as intimate. Hence there is a sense in which “intimacy” means “clarity.”

The Nigerian writer Emmanuel Iduma on the art of writing.

Photo by Jacqueline Iannacone.

Children Begging on the Street

In Ngor, the wealthy part of Dakar where we lived for close to two weeks, the street was often filled with children of varying ages begging.

In speaking about the lack the children are imagined to possess we speak from a position of abundance. Abundance, in my Dakar experience, is the feeling that my empathy was irreverently confronted by the requests of the children. They tugged at my sleeves, whispered words of appeal, following sometimes for a quarter of a minute. I responded once or twice with spare change, half-filled bottled water, or on one occasion I paid for sandwiches for three of the children. In a bizarre way I thought my response was a measure of my guilty materiality, like it is when people are said to make money by diabolical means.

*

The emptiness I feel in revisiting this experience is equidistant to the emptiness that is at the heart of begging. Put clearly, begging is conceived as neediness; to talk about it we distinguish between what is owned and what isn’t. In parallel, the emptiness I felt was my attempt to think of begging outside the idea of neediness. These emptinesses converse and interact but also antagonize each other. They converse and interact since one possible fate of a person of privilege is to readily notice an underclass. And they are readily antagonistic because the emptiness of not-having is not the same as the emptiness of unable-to-speak.

*

These emptinesses will converge when emptiness becomes a kind of abundance. Clarice Lispector in The Hour of the Star expressed in clear terms the nature of this emptiness: “But emptiness, too, has its value and somehow resembles abundance. One way of obtaining is not to search, one way of possessing is not to ask…” The first task would be to under-indulge the idea of neediness—to think of begging as an act of being present in the world, as a way these children navigate the alleyways of survival. We must begin with this opaque metaphor of “being present” because it might open us to an unfamiliar perspective on possession. In this case, possession will not work as a function of commodity, but as community—that is, the “possession” of ourselves. I shared a presence with the children when they walked beside me, bowl in hand.

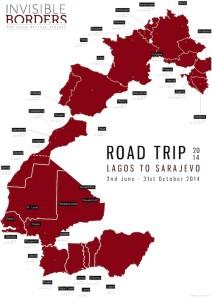

“Photo of the Invisible Borders van, 2014. Courtesy Emmanuel Iduma/Invisible Borders.”

It is by turning to the possibilities of our coexistence that I can begin to navigate my emptiness.

But our coexistence remains unimaginable since I scarcely spoke to any of the children. It is a coexistence that begins with an inner silence, an inner unable-to-speak and unable-to-approach; not for want of want to say, or for want of smiles to put up, or for want of courtesies to distribute, but it is the lack of ways to become less of an outsider to an experience. It is feeling pity and yet being nagged by the lack of permission to feel pity.

*

Once an experience is told it is contextualized. I know this because I am muted by the various—politically correct—ways in which begging is talked about in and outside Senegal. It became strategic to think of begging outside of the usual talking points—although context is useful it can be broken apart. One possible talking point would be hope. These children, we might say, have a bright future ahead yet they end up on the street manipulated by their families and Marabous. Instead I turn to the small victory usually won when a child is given a coin after almost a minute of pestering. And I equally turn to the child who seconds before begging played football with a friend—on the street where the benefactor is walking—alternating between work and play. Hope in these instances arrives in the next instant; it is not deferred. It seems to me the child will think about hope this way.

*

The unsteady narrator in Lispector’s final book tells the story of Macabéa, who has nothing and is nothing. It reads like a story about emptiness, about the nature and value of zero. The kind of empathy we arrive at when the story is brought to a close is empathy without pity. Instead, it is an excruciating empathy that comes from the rigor of coming to know Macabéa. We do not pity her; we know her.

To reiterate: it is the rigor of coming to know that makes empathy possible. Once we apply this logic to Dakar’s begging children, we recognize that the knowledge that will make us fully empathetic is hard to obtain; for we are blinded and made ignorant by the commodities at our disposal.

Subtext: By deciding to work on an idea while on the road, I disturb the basic intimacies of a place.

What I make of this disturbance is of course left to me. I am saying to people: Your everyday ordinariness and mundaneness means a lot to me, and I’m talking about it in ways you might not. The people of the places I visit are invested in this ordinariness in intimate ways I might not understand. My task is to delve into this intimacy despite my ignorance. Writing is a way to disturb the materiality of an environment: the things I see and think are familiar, the position I take and think are justifiable, and the stories I tell to explain my lack of intimacy. It is in this regard that I remember Iain Chambers: “the disturbing materiality of writing—the hand, the body that produces a space in which the lives, events, and the past are interred—is not so much written over as written up and inscribed in the account.”

*

The danger is that I might be mired in a broth of my own making. This broth is the skin of my identity that I carry about (and if one digs into this identify, which is sometimes simplified as “Nigerian,” there’re other turns and twists). How do I assert that I am mired in my broth while delving in the intimacies of the environment I visit? Perhaps the answer to this lies in the physical act of writing itself. Writing is an intimate gesture; by being in a place and writing about it one automatically begins a process of reconciliation—being reconciled to the breaking, shaking, irritability, and nausea that is the destiny of an intimate stranger. “Writing itself,” notes Iain Chambers, “becomes the site of such folds, creases, and detours, where sense runs in multilateral movement, always falling short of the conclusion.”

*

Since writing “becomes” a “site” we know it is driven by the need to be specific, to stay rooted. This specificity might be in the active writing about place(s), as is my imperative on the road trip. Yet I believe to be specific means to affirm a certain context by wearing one’s conviction on the sleeve. It means to respond to the particularity of a moment; because to be intimate is to show how the specific cannot be glossed over by the general.

*

The process by which one comes to know is similar to how paths are cleared. A writer clears his path through incessant questioning—seeking more than anything else an honest evaluation of his position and place in the subject’s affairs. Devoid of any irrelevancy and unpretentiousness, a piece of writing will consequently function as honest, and as intimate. Hence there is a sense in which “intimacy” means “clarity.” While on this trip I understand that to seek an intimate involvement in these cities is to articulate in clear terms what I feel frustrated or excited by, and what ideals I am tormented by.

•