Ward manages to express his ideas and thoughts in a sheer endless amount of forms. Even as somebody who is familiar with a lot of his works, he always surprises me, he always makes me wonder. Although the content can be heavy and emotional, there is always a lightness in his work. A smile is not forbidden.

Rob Perrée on Nari Ward.

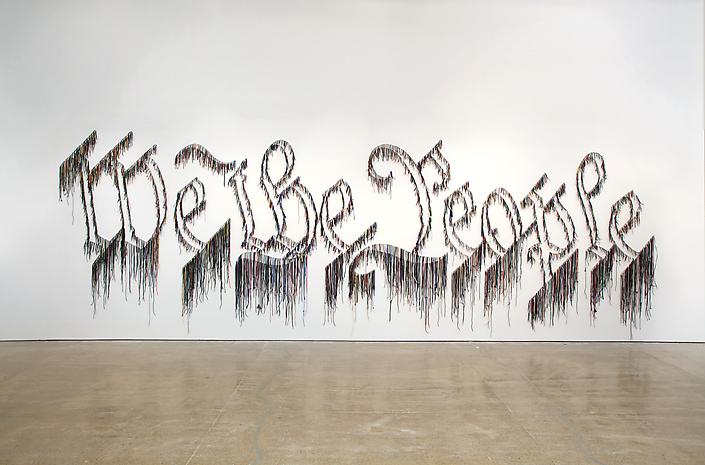

Ward working on ‘We The People’, 2011.

NARI WARD’S REALITY

It is the smallest work of the exhibition, but it has a large impact.

Two little cans are standing next to each other in a showcase. The left one is ‘dressed’ in yellow, the right one in black. The left one has the brand name ‘Jamaican Smiles’ and is made in Jamaica, the right one is called ‘Black Smiles’ and is made in America. Both are supposed to be distributed in Italy.

Canned Smiles, 2013.

Nari Ward (1963) is born in Jamaica, but is living in the US since age 12 . He lives in Harlem now. ‘Canned Smiles’ (2013) is a reference to his double identity. Being an immigrant who still has his memories about Jamaica , but is too much of an American now to have full access to current Jamaican culture. At the same time he is not enough of an American to have the feeling that he is really part of black Harlem where African-American culture had its renaissance a hundred years ago. His kids however are born in the US. They are black Americans. Therefore he canned himself in the ‘Jamaican Smiles’, his kids are canned in the ‘Black Smiles’. At the same time he addresses the cliché of the smiling Jamaican and the smiling minstrel American. He addresses the difference between the way certain groups are represented and the way they really are. Since the work is inspired by Pierre Manzoni’s canned ‘Artist’s Shit’, Ward credits this work of the Italian artist with the text ‘Distributed in Italy’.

*

This work fascinates me because it proves not only that a simple appearance can hide a complex meaning, it also proves that simplicity can be an excellent trigger to open up curiosity. In this kind of work the influence of David Hammons becomes visible. His hood (‘In the Hood’, 1993) and his flag (‘African-American Flag’, 1990) could have inspired Ward.

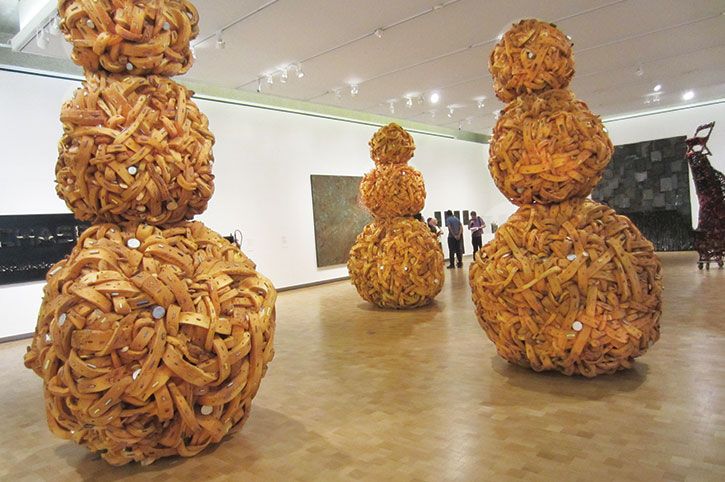

Installation view 2016 (foreground Mango Tourist)

It is hard to say what Ward’s work is about, because it is about many things. It is not only about immigration, it is also about power, about ownership, being black, about tradition, about hypocrisy, about Jamaican-ness and about the difference between expectation and reality. In spite of the differences in themes, there are a few generalities: the work is always committed, rooted in the world he lives in, reacting on what happens around him and in the world at large. It always gives the viewers the ingredients to create their own narrative. “(…)I am trying to give them just enough so they think they know what they are looking at but then they have to construct their own narrative around it”. Or, more poetic, “(…) wanting the work to be almost like a bag for people to put things into (…)”.

Amazing Grace, 1993.

Both general characteristics are exemplary in ‘Amazing Grace’ of 1993. In that installation he brings together 365 strollers in an abandoned firehouse, picked up from the streets of Harlem, discarded by the people living there. Fire hoses are connecting the different elements. Mahalia Jackson sings ‘Amazing Grace’. Most visitors in that neighborhood must have been familiar with what they saw and heard. Because of that their curiosity must have been triggered: Why these objects? What does it all mean? Are the strollers a symbol of a community in crisis or are they referring to a hopeful future? They have carried babies but also the bottles and tins of homeless people. Do the firehoses – cut in pieces, out of work – symbolize the hopelessness of the situation? Is that the reason why Ward chose that abandoned location? Why ‘Amazing Grace’? Why the Mahalia Jackson version? Because it was written by the Christian poet John Newton, who was involved in the Atlantic slave trade? Because Jackson’s version played a role in the Civil Rights Movement? Sufficient building blocks for a personal narrative.

Iron Heavens, 1995.

Nari Ward uses varied media. Photo, sculpture, installation (sometimes interactive), video, assemblage. Most of the time he uses existing materials or objects. Not only because they have a history but perhaps even more because they inspire him, they talk to him, they tell him a story. By combining them – he likes the word ‘weaving’ better – he creates an answer, a new meaning, a new story, a new reality. They give him the possibility to bring the past to the present, the hidden to the public. ‘Iron Heavens’ (1995) is a view built out of used oven pans of different design and age suggesting a heaven with stars. A big amount of roughly grouped baseball bats suggest the land below the horizon. A night sky materialized? The bats are applied with cotton and partly burned. The association with race related violence could be made. On the other hand, in the new reality of Ward, they play a positive role. The oven pans are normally hidden in an oven. Burned, dirty, only functional. The artists beautifies them, makes them heavenly. Through his hands the bats become very decorative. Apart from these metaphorical interpretations, the work can also be seen as just an abstract sculpture with a strong presence.

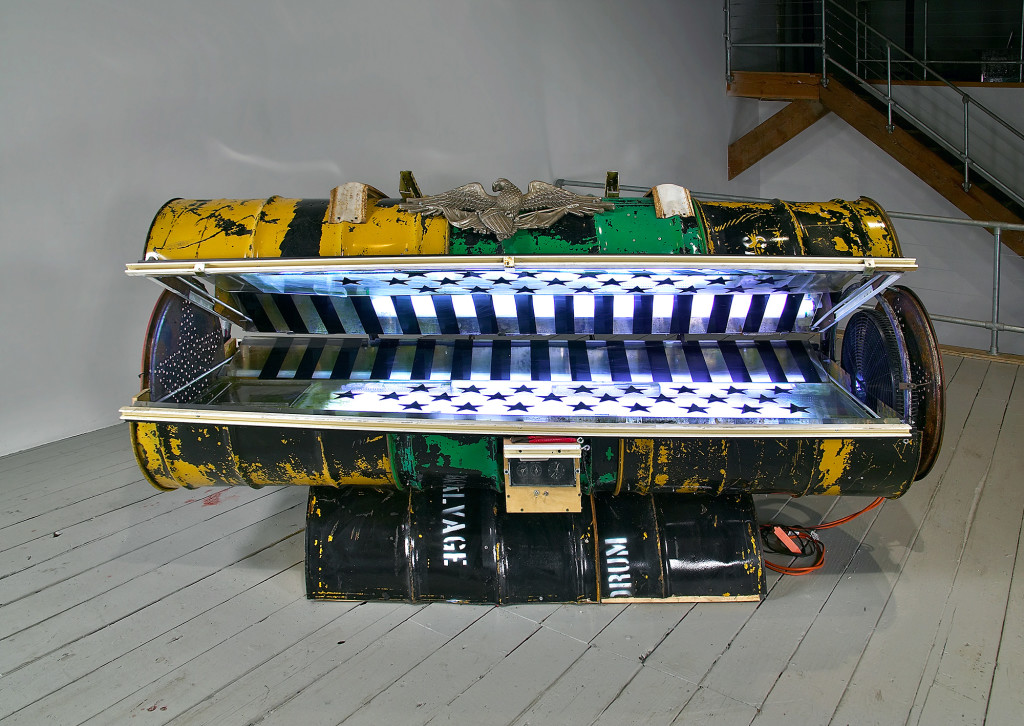

Glory, 2004.

‘Glory’ (2004) is a more complex work. It looks like a tanning bed dressed up with contradictory elements. The outside is covered with used oil barrels – split in half, eagle on top – ; on the inside stars and stripes are printed on the lightboxes with fluorescent lights. The sound is from a language training CD for parrots. Is this a parody of recent American history? The American army invading Iraq for dubious reasons, supported by allies who did not (want to) check the facts? Followed by extreme nationalism after September 11th ? Is this adding a new meaning to an existing story inspired by found objects?

Breating Panels, 2015, installation view.

Breathing Panel (detail).

Last year Nari Ward presented ‘Breathing Panels’ (2015) in his gallery in New York. An abstract, almost minimalistic installation. More cryptic than most of his earlier works, because the recognizable found objects were missing. Copper panels were put on the floor and on the walls. Carl Andre 2.0? A closer look gave more information. The panels had a blotchy surface. The artist had walked over the copper panels with a dark patina under his shoes. The ‘dirty’ spots were traces of a performative act. He also had punctured geometric patterns and holes in each panel. A reference to traditional Congolese cosmograms, spiritual symbols which represent the cycle birth-death-rebirth and a reference to the holes in the wooden floor panels in churches in the south, made to allow escaped slaves, hiding under the floor, to breathe. Does the walking act stand for escaping? Hiking instead of hiding? Or for walking on memory lane? What does it mean for non-black people to walk on or over it? Are the panels a mixing or mingling of two different cultures? Symbolizing the experiences of an immigrant trying to gain a foothold in a new world?

We The People, 2011.

The stories of Nari Ward have an open ending. They start from personal experiences, but they are “woven” into works with a possible universal meaning. Familiar objects get a new context and create, because of that, different realities. I use the plural because the works just hand tools to the visitor, giving him the means to create his own story, his own reality. Ward manages to express his ideas and thoughts in a sheer endless amount of forms. Even as somebody who is familiar with a lot of his works , he always surprises me, he always makes me wonder. Although the content can be heavy and emotional, there is always a lightness in his work. A smile is not forbidden.