Even now the ‘black sound’ is a constantly energetic and evolving creature. With more and more cross-genre records being dropped across Dance and Pop regularly there is little doubt that black music is the mainstream sound and market leader across the Western world.

Christabel Johanson on Black Music in the UK

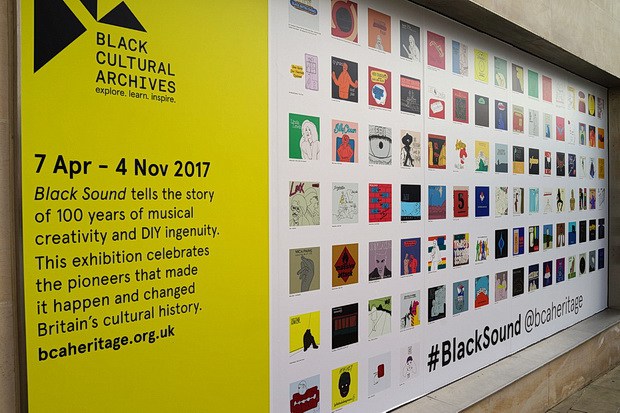

Poster exhibition Black Sound

Black Music in the UK

Black Sound Exhibition London

At the end of November the UK celebrated another year of strong black music. The MOBO (Music of Black Origins) Awards headlined with names such as Stormzy, Steflon Don and Tokio Myers amongst several others. Internationally the genres of Hip-Hop, R&B, Rap dominate the charts. So how did these styles, once looked down upon as just ‘black music’, come to be the mainstream favorites that they are now?

*

Well the Black Cultural Archives are running the Black Sound exhibit which explores this musical journey over the last 100 years. From the sidelines to the forefront of society, black music has overcome and become the status quo. Combining audio, visual and historical sources to bring the story to life Black Sound covers ‘Original Imports, D.I.Y Culture and Re-mastering the Mainstream’. In doing so the exhibit features the pioneers, the generations and the growth of the UK’s multi-cultural musical landscape.

Installation view, photo Mike Urban.

1919 saw the Southern Syncopated Orchestra – whose members hailing from New Orleans, the West Indies, New York, Africa – banded together to produce a Calypso/Jazz sound that toured London’s West End before performing for royalty and 100 guests at Buckingham Palace on 19th August of the same year. The group popularized black music within Britain and across Europe. Band members settled in South London, married English women and their mixed race children were the products of this fusion. By 1921 many of the bands were on their way to Derry, Ireland to continue their tour of the United Kingdom. However the ship was involved in a collision and several members were lost at sea. The tragedy was reported widely in the newspapers but the band never quite garnered recognition in history books. Thankfully this exhibit and others are allowing these stories to be rediscovered and the unsung heroes to be lauded.

Rudolph Dunbar

By the 1940s we had the first black orchestral conductor by the name of Rudolph Dunbar. He was a Guyanese conductor, composer and clarinet player. He was also the first black man to conduct the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in 1942. In his long-spanning career Danbar left behind a clarinet school, wrote for music magazines as well as refined his own system for playing the clarinet which is still the standard today. Dunbar conscious of his accomplishments once said ‘The success I have achieved through sacrifice and struggle is not for myself, but for all the colored people’. Proving himself to be a pioneer in music, Dunbar remains a pivotal figure in breaking down barriers as well as representing the excellence of black musicians to an international audience.

Installation view, photo Mike Urban

Then at the end of the decade another important figure; Lord Kitchener arrived in Britain as part of the first wave of West Indian immigrants. On the Windrush, which sailed to Britain with its workers, were Trinidad’s two top Calypso musicians Lord Kitchener and Lord Beginner who would later record at EMI studios. The artists would sing about life in Britain; ‘Cricket, Lovely Cricket’, ‘London is the Place for Me’ and ‘My Landlady’ were some of the tracks they produced here whilst they fully embraced the changes, quirks and lifestyle in England.

Reggae soon followed in the 1960s as well as Dub and Trojan and musicians like Tipie Irie or Smiley Culture eventually exploded onto the scene with Liverpool, Birmingham and London becoming Britain’s main hubs of black music. Meanwhile Soul was also gaining recognition as the genre to accompany the dramatic political landscape during the UK and USA’s civil rights movements. Sam Cooke’s ‘A Change Is Gonna Come’ was probably the definitive anthem of the time and change did come in the 1960s not only for black rights but for Britain’s music scene. In 1966 the Notting Hill Carnival also moved to the streets adopting the format it is popularly known for now. A celebration of the African and especially the Caribbean roots that Britain’s immigrant population of West London shared, the carnival was a platform to showcase the dance, music, food and vibrancy of black culture. Today it is one of the most exciting events in the capital’s calendar, bringing in hundreds of locals and tourists to share in the festivities.

Installation view, photo Mike Urban

By the mid-80s DJs Trevor Nelson and Norman Jay were regulars on the airwaves and Kiss FM radio station began to play mostly black music. Soul II Soul formed and broke into the charts with ‘Back to Life’ and ‘Keep On Movin’. Jazzie B, Doreen Wadell, Caron Wheeler, Daddae, Rose Windross, Jazzie Q and Aitch B were the official original members and their combined sound would be the beginnings of UK Hip-Hop. The band’s look was Afro-centric and its members did not shy away from this. In fact their fashion was named ‘Funki Dred’ and established a clothing line off the band’s success and popularity. The group won two Grammy Awards and was nominated for five Brit Awards and in 2007 reunited to play at the Lovebox Festival, proving that their appeal hadn’t waned. Today they still perform at grass root levels, like at the Electric Brixton where Caron and Charlotte lead on vocals.

Then in 1988 ‘Voodoo Ray’ by Gerald was released and fused Manchester’s rave scene with London’s Jungle music. The ability of black music to flex its sound became one of the big reasons for its popularity and growth. Blending from one distinct identity into a hybrid ensured that the spirit survived and gained acceptance with a wide section of audiences. For example Garage’s sound derives from the need of punters in Jungle raves for a calmer alternative to its frenetic sounds.

*

In the late 90s Goldie released ‘Truth’ featuring David Bowie and together Drum n’ Bass hit mainstream ears. Garage and Drum n’ Bass dominated the noughties with acts like So Solid Crew, Artful Dodger and Craig David featuring on popular music platforms like Top of the Pops or MTV. By this point ‘black music’ was already an integrated component of British music and British life. Clubs, pubs and bars all over the country would feature black music hits as a standard background playlist. As part of the music that shaped the noughties, songs like ‘Do You Really Like It’ (DJ Pied Piper), ‘Moving Too Fast’, ‘Rewind’ (Artful Dodger), ‘Dy-Na-Mi-Tee’ (Ms. Dynamite) were heard everywhere and are now known as Garage classics.

In 2002 Ms Dynamite won a Mercury Music award. She also received two Brit Awards and three MOBO Awards during the height of her career as well as performing at the closing ceremony of the Commonwealth Games and Live 8 in Hyde Park. In the same year Radio 1 Xtra was established specializing in urban music with dancehall, gospel, soca, reggae and R&B taking the spotlight as part of its remit in representing black sound. Its mission was to champion diverse UK underground music which it continues to do to this day.

*

Even now the ‘black sound’ is a constantly energetic and evolving creature. With more and more cross-genre records being dropped across Dance and Pop regularly there is little doubt that black music is the mainstream sound and market leader across the Western world. Rappers lend verses in most chart songs and London still remains a trailblazing city for fresh, original music. By constantly developing its own unique urban flavor, the capital prides itself on continuing a long standing tradition that started over 100 years ago when Dunbar, Lord Kitchener and the Southern Syncopated Orchestra arrived on British soil, enriching it with their own cultural heritage. Would Britain have been the same without these pioneers? Likewise would black sound have evolved without fusing the old world with the new?

*

The Black Cultural Archives presents no moral conclusions but rather gives the space for viewers to digest the rich heritage for themselves. As with all colonial history, the cultures that are created as a result of Empire-building can be difficult to be at peace with. However this is not the concern of the exhibition. Instead it charts out the landmark moments and milestones of a remarkable century that really changed the face and soul of Britain.

Walking through felt like visiting a living museum with its posters and newspaper cuttings stuck along the walls, the exhibit is reminiscent of a music-lower’s bedroom. Stereo systems with cassettes, record players and head phones are plugged in invitingly for you to hear and enjoy for yourself. Sitting there, eyes shut or reading the lovingly collected scraps bring us back into our own ‘teenage bedroom’. By evoking the same wonder and delight we are perhaps put in the position of those youngsters, pioneers and punters who over the years have marvelled at their heroes shaping the future sound of black music.

*

Maybe in another 100 years there will be an archival exhibition featuring today’s Grime artists revered as big players in tomorrow’s world; after all when Rudolph Dunbar picked up his stick or when Lord Kitchener cut his first record, they probably didn’t think they’d be the first of many black musicians to pack out concert halls with people ready to embrace the black sound.