In London the Black Cultural Archives hosted a pop-up exhibition covering the stories of Britain’s mixed race babies from American GIs. The photographic exhibit is based on the children born to white women and black Americans. This dichotomy of a bi-racial identity has long existed in social, racial and political affairs. Historically however it has not been given the space to be explored neither by the white status quo nor the black community. Herein lies the difficult conversation of navigating between both worlds and whilst feeling no belonging to either.

Christabel Johanson on Mixed Race in Art

Genevieve Gaignard, Miss/ed America, courtesy Vielmetter, Los Angeles

Being Mixed Race in Art

In London the Black Cultural Archives hosted a pop-up exhibition covering the stories of Britain’s mixed race babies from American GIs. The photographic exhibit is based on the children born to white women and black Americans. This dichotomy of a bi-racial identity has long existed in social, racial and political affairs. Historically however it has not been given the space to be explored neither by the white status quo nor the black community. Herein lies the difficult conversation of navigating between both worlds and whilst feeling no belonging to either.

*

In Britain particularly with the influx of immigrants from the West Indies and Africa, mixed raced communities across the country have created their own unique culture. Nevertheless for those individuals who share black and white parentage, charting their heritage can be a challenging and confusing task – especially when they are geographically distant from one side of their family. However the arena of art has taken on this challenge to explore what it means to be bi-racial in the world.

*

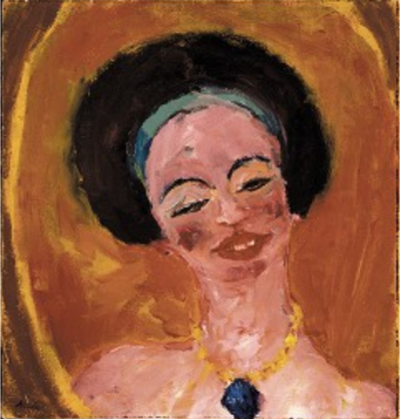

Earlier works give us The Mulatto by Emil Nolde. Nolde is said to have spent winter in Berlin where he spotted this woman in what was fast becoming a diverse capital city. Her jewellery and make-up would suggest she is an actress, singer or performer. The title reveals his interest in the woman is based on her racial identity.

The Mulatto, Emil Nolde, German (Nolde, Germany 1867 – 1956 Seebüll, Germany)

A Mulatto Woman by Eugene Delacroix presents an exotic and sensual vision. The woman nearly has her breasts exposed for the portrait. Perhaps this was because at the time bi-racial people were of lower social status than whites, especially females, so this sort of exposure might have been less scandalous for a person of color. However her face looks bashful and in this pose we feel like she is somewhat vulnerable. Unlike Nolde’s painting, this woman is less confident, she is dressed down, more sombre and her hair is down in the style of white women. Between the two examples she looks more disempowered and fitting more into the contemporary notions of inferiority.

A Mulatto Woman, Eugene Delacroix (c.1821 – c.1824)

Fast forward over a hundred years and today’s artists are taking a more complex look through the bi-racial lens. From studies of mixed race children like the ones shown in the Black Cultural Archives, through to the grassroots projects today’s mixed race artists offer, these artists are owning the images of their community and not just being the voiceless subjects of a white lens.

When photographer Tenee Attoh began taking a series of pictures amidst a South London backdrop, little did she know where it would lead. The Bussey Building in the Peckham neighbourhood hosted Attoh’s friends and family to the photoshoot where she captured their faces and the stories they had to tell. Attoh is of Dutch and Ghanian descent and says “there’s still a lot of ignorance in society. People perceive you as either black or white, and you’re not – you’re mixed.” The issue with fitting into one camp or another has been a problem that most mixed raced people will encounter in their lives. What Attoh works at is raising the platform for mixed race people to be viewed as an identity in their own right and not just a sum of two races. As an homage to her late Dutch mother, Attoh’s art work connects two worlds in order to further diversity and what it means to have a mixed heritage. She says it has given the subjects a sense of belonging and ability to belong to both cultures.

Paksie Vernon. Photograph: Attoh Tenee

Mixed Race Faces, installation view 2019

Attoh has taken of 90 images and counting, and in Summer 2019 exhibited the images in the Copeland Gallery in London. However this is just chapter one in a continuous series of art work that will provoke its audiences in revaluating their understanding of race.

*

Genevieve Gaignard is a Los Angeles-based artist and photographer. She uses sculpture, photography and installations to examine race and themes such as “passing” for white, invisibility and mixing racial realities. Having a black father and white mother, Genevieve has interrogated what it means to be both black and white and neither. In her work she uses props such as clothing and wigs to heighten the visual signifiers of a particular demographic. “I describe my art practice as an extension of what it’s like to be in the mind of a biracial person. I’m playing a lot with stereotypes. Playing up aspects of generalisations made on people, but specifically on myself. I pass as white so I play with that.”

The Powder Room is one of Gaignard’s installation offerings, which intersects her explorations of race between white and black through an ensemble cast of female characters – all played by herself. She portrays white characters juxtaposed with black signifiers. The label of “powder room” is supposed to provide a safe confessional backdrop for Gaignard to play with the identities, dress up, use make-up and explore race. For Gaignard she is both the artist and art work in this exhibition.

Genevieve Gaignard, Supreme, 2015, courtesy Vielmetter Los Angeles

In the piece above, Gaignard is dressed in the hairstyle and fashion associated with black culture. On the surface, with Gaignard passing for a white person, the audience may consider her appropriating black fashion. However in the context of understanding her as a bi-racial woman, we can empathise with the idea that this person may live in a state of conflict between her dual heritage and the way the world perceives her – and the judgements they make on her appearance. We may see her as a white person exploiting black styles, but the reality is she is expressing an authentic part of her identity. This difficulty is something that Gaignard and many other mixed race people wrestle with, “I’m constantly thinking I am not enough of either/or to navigate through the world.”

Genevieve Gaignard, Basic Cable & Chill, 2016, Courtesy the artist and Shulamit Nazarian, Los Angeles

“When I watch a TV show, and a character walks in, I’m scanning the background to see which objects they use to inform who they are. I do this when I go to people’s homes too. I make these observations, gather that information and play with how things are juxtaposed.” This is Gaignard’s approach when creating a mise-en-scène like the one above. She portrays a woman with an afro which strongly positions a black identity. However the figure is light-skinned so this places her perhaps in a bi-racial space. The home she stands in front harks to the poorer neighbourhoods in Los Angeles. Gaignard stirs a stereotype here of the “ghetto” woman through her clothing and backdrop.

Yet in her portrait below she fluidly adopts the identity of a blonde white girl. So powerful are her transformations that the audience make snap judgements on her character and personality based on the garb she dons. It is only when one watches interviews with the artist that a more accurate idea of her is constructed, rather than the one she has produced. However this snap judgement makes the viewer reflect on our own prejudices and conditioning towards not only race but shade of skin.

Genevieve Gaignard, Grace, 2015, Courtesy Vielmetter, Los Angeles

Whilst Gaignard’s and Attoh’s work seeks to amalgamate identity in their own ways, both artists bring important discourse on race to the surface. Whilst white-led art is present in institutions and black-led art has had its movements and space for curation, it seems that the mixed race art scene is only just gaining momentum. As with communities that have experienced marginalisation or resistance into being absorbed into a larger collective, the biggest milestones are for bi-racial portrayals (in media, art, society etc) to be brought back into their own hands. Both Attoh and Gaignard are two artists that are leading this reclamation of the image of the old-fashioned “mulatto”.