I think Mali has everything to offer. In this culturally rich country, artists are very open, knowing how to share without condition. This makes us exemplary.

Joyce Pennekamp on the art collectives in Mali

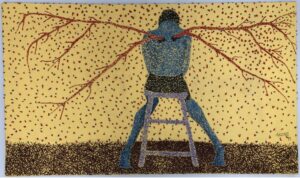

Abdoulaye Konaté, rouge vert au kente, 2020

On est ensemble

Challenges and strengths of Malian art collectives

These turbulent times accelerate the re-imagination and reshaping of many, if not all, societies. Chinua Achebe’s key observations in Things Fall Apart are now even more relevant for societies like, for example, Mali. Once an endless, culturally rich empire, but since the coup d’état and jihadist invasion in the northern region in 2012, Mali is caught in an endless struggle. When things fall apart, people unite. On est ensemble (we are together) is a frequently used expression by young people (and ironically, politicians) as a way of expressing unity, after an agreement or a talk about something that matters. Does this spirit of collectiveness explain the collaborative way of working of the younger generation of Malian artists?

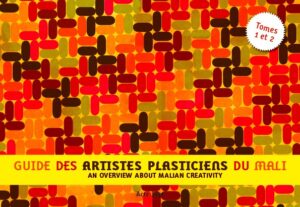

During frequent visits, I gradually discovered the contemporary art scene in capital Bamako. At first glance it is as complex as a map of a medina. You can easily get lost in the many names and initiatives that compose a lively art ecosystem. It requires quite some conversations and time before you come to see the main structure and connections. This complexity also consists of the present importance of past traditions and ancestors that built Malian culture. You need more than a lifetime to truly unravel the complexities and mysteries that lay beneath. A contemporary extended edition of the Guide des Artistes Plasticiens du Mali (2010) would be convenient, to start with.

Within the scene, a distinction is made between the younger (les jeunes, as they are called, are in their late twenties, early thirties) and the older generation. With all due respect for the “older ones”, I highlight the development that is said to be typical of this younger generation: creating art in collectives. I invited Hama Goro, founder of visual art center Centre Soleil d’Afrique (CSA) to share his experienced insights. I invited the founding members of some of these collectives to join a conversation: Seydou Camara of Yamarou Photo, Fatoumata Tioye Coulibaly of KILE/KINO Bamako and Mariam Ibrahim Maïga, Ibrahim Ballo and Ange Dakouo of Tim’Arts.

Why did this generation decide to work collectively? How do they manage the challenging circumstances of instability and insecurity? How do they see their role in Malian society and envision their future?

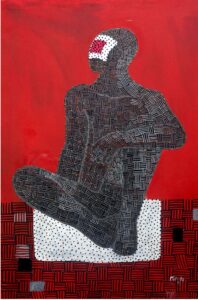

Ibrahim Ballo, Apparence Rouge, 2018

Soil for a collective way of thinking

There are many imaginable contextualities related to the development of collectiveness. You might also wonder: hasn’t it always been like this? To understand the current structuring of the art scene through collectives, a small retrospect is insightful.

Socially, groups have always marked Malian society. Each individual belongs to a group, a tribe, family, a geographical community and a grin; a group of neighbours that daily gather on the street for tea ceremonies and discussions. Living in communities does not necessarily need to be transmitted in collaborative artistic practice, but it enables individuals to think from a communal point of view.

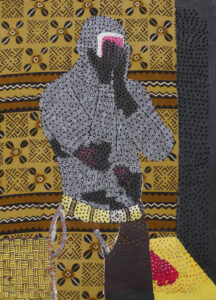

Ange Dakouo Bouquet, Mystere, 2020

Cultural activity augmented in the 90s and early 2000s, creating soil for an art scene in which (international) collaborations and crossovers were common. Possibilities in education and exhibiting increased. Boosting “laboratory”centres were installed, like for theatre Acte Sept by Adama Traoré, and CSA by Hama Goro. The concept of collaboration was key for their foundation. Hama explains: “after I finished my education at Rijksacademie in Amsterdam (1997), I wanted to create a space in Bamako for young artists to be able to collaborate, to meet, discuss and create together and with international artists, like I’ve experienced this at Rijksacademie. In those days, most artists worked individually. I wanted to share these experienced benefits of collaboration and create dialogues.“

International events were established, like the Biennial for African Photography, Rencontres de Bamako in 1994 and Festival sur le Niger in Ségou in 2005 by Mamou Daffé, both important, collaborative structures on the African continent. Musée National du Mali opened in 2003; a new art academy, Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers Multimedia (CAMM) was founded by Abdoulaye Konaté in 2004. Souleyman Ouologuem started stimulating artistic collaboration in his association Anw-Ko Art in 2007. In 2011 Lassana Igo Diarra installed Galérie Médina, now an internationally renowned art space with innovative exhibitions and meeting opportunities for art professionals.

2012 Caused an abrupt decline in cultural activities and somewhat later, the younger generation of artists started to group in collectives. Most of them were about to finish their education at CAMM, where they studied together. A clear need raised to not face these new circumstances individually. Economically it was more attractive to rent a space together. The ongoing activities in CSA also played a stimulating and emancipatory role in the collaborative need of these artists.

Tim’Arts: raising awareness through education

Groupe Silence Coupable, 2019/Mariam-Niaré

In 2014 Mariam Ibrahim Maïga decided to start a collaboration with fellow art students at CAMM. Soon other collectives appeared, like the well-known Badialan by Amadou Sanogo as well in 2014, or Sanou’Art (2018) and most recent Atelier M in 2020. Starting with five, Tim’Arts now consists of ten members. Their collective space is a private house where they create, exhibit and store their work. Chairs, materials and a small stove for the tea ceremonies are gathered in the porch. The large tree not only provides shadow, but also an intimacy for in-depth conversations and discussions.

Ibrahim Ballo, Chaleur au font, 2021

Ibrahim Ballo, member since 2015, is gradually gaining more visibility in Africa and Europe. “It is one of our goals to promote art in and outside Malian society. Visual art is not seen as an important expression of culture, like music. Collectively we can do much more and besides developing ourselves, we can also help others to develop. That is why we developed an educational program for children -Art’Enfant- in which we teach them to express creatively and get to know art techniques. In general, we need more education. Art and science at CAMM, a faculty of Art History at the university and the possibility to study art education are all necessary to develop more knowledge and research. The enlarging influence of Islam also means that culture is neglected.”

Ange Dakouo,Envol, 2020.

Ange Dakouo, member since day one, is now a well-known artist. He explains the need for collectively promoting art within Malian society: “there is no art education in public schools, how can we expect Malians to know what is created in their own country? With Art ‘Enfant we want to contribute to the development of art education. Raising awareness and increasing visibility is much needed.” For their own development, they attend and organize workshops or residencies. Ange: “Quartier Libre is a residency for all collectives. Each year we experiment during a month, free from thematic pressure that is usually imposed on workshops. This free flow of exchange benefits for all.”

Abdoul Karim Diallo

Collaborating in relatively small spaces can also have its disadvantages. Inspiration and influence can become copying. Success for one can both be motivating and demotivating for the ones who are not yet. It cannot be unnoticed: observing Malian contemporary art, you can see influences from the work of successful artists like Abdoulaye Konaté or Amadou Sanogo. Influences within the collectives, thematically and formally, are also visible. Ibrahim: “sure, we are influenced. As well there is a tendency to follow what is successful. But we give our personal interpretations and try to develop our own signature. We feel it is important to preserve knowledge and techniques, to pay respect to our ancestors, express our solidarity, show our relations with and contribute to our traditions. That is what distinguishes Malian art.” To this idea Hama Goro adds an insightful thought: “I see Malian, or African, art parallel to Western art. We have our own history, techniques and vision on what art should be. Western art theory is not necessarily fitted to analyse our way of creating art.”

KILE/KINO Bamako: film education as a tool for social cohesion

I first met photographer-videast Fatoumata Tioye Coulibaly when she just finished CAMM in 2016. She had clear ideas about what went wrong in her country and expressed her opinions openly. This is exceptional in a society where opinions and thoughts are not publicly exposed, in particular by women. In 2018 Tioye converted her passion for film and education for uneducated young adults by establishing the Bamako edition of KINO, an international movement for making short-film with a low budget. KINO is one of the activities of the in 2009 founded KILE collective, of which she is now president.

Tioye’s key activities are educational programs and screenings throughout Mali and surrounding countries. Learning how to create short films has already given several uneducated youngsters the opportunity to find a job in the audio-visual domain. Others created short films and even gained prizes. As there is no cinematographic education in Mali – only CAMM provides some workshops- Tioye aims to develop a generation of filmmakers that is skilled in digital media. “Film for me is the most important tool for communication, education and raising awareness for the realities of our country. In a contemporary digital way, we can display our traditions and values, transmit our oral tradition into a visible one. As we also work in the abandoned areas in Mali, like in Timbuktu or in refugee camps, we hope to contribute to the emancipatory development of our country. The humanitarian and political crisis created an urgent need to mobilize members of our collective to develop initiatives that contribute to social cohesion and facilitate peaceful coexistence.”

Yamarou Photo: education for talent development

Seydou Camara, Série Sufi.

Lack of education also motivated photographer Seydou Camara to install Yamarou Photo in 2017. Some courses are offered by art academies INA and CAMM. CFP (Centre de Formation en Photographie) only execute courses occasionally. The younger generation is mostly auto-didactic and lack proper guidance to build their portfolio. Many photographers report the abundant social events like marriages and baptisms, but are not capable of extending their skills. Seydou developed an extensive curriculum in technique and content. He also initiates cross overs with other art initiatives and international exchanges in online meetings. Some of the now eight Yamarou-members give courses in other countries like Guinée or Burkina Fasso.

By lecturing the courses in Bambara and not in the official French, he stresses the importance of Malian identity. The fact that Malian photographers are rarely selected for Rencontres de Bamako, inspired Seydou to initiate the L’Interbiennale. “With L’Interbiënnale we promote our photographers by exhibiting in communities. We also enable them to gain experience, to meet the required qualification level of Rencontres.” He regrets the little attention given to art: “hardly any Malian visits exhibitions, it is always a selected group you encounter. An art market is almost absent, art collectors are rare. So, governments are even less interested to install an educational system. We also discuss the “quick fix” learning opportunities through short term workshops, organized by foreign NGO’s. “We are of course happy to engage, but we aim for durability.”

Acts of resistance

The welcoming and hospitable attitude of the majority of Malians is in contrast to the violence and armed militaries. The attitude of artists towards politics is seldom aggressive. In their works, Malian metaphorical and symbolic approach to reality is visible. Musicians, especially the “rappeurs” and “slameurs” are much more outspoken in their critical lyrics. Artist Abdou Ouologuem takes a unique position, by publishing critical video-monologues on Facebook in which he questions the many challenging issues.

Alassane Koné, Le miroir royal, 2021

Tim’Arts organizes exhibitions that reflect on current situations. With Silence coupable in 2019 they raised awareness against Malians inclination to mute their circumstances. Often their “activism” is much more humanitarian, by executing assignments for NGO’s, like founding member Mariam, on her way to Guinée for a report when we communicate via whatsapp. She writes: “artists have a more mediating and preaching role in our society, but they are not understood enough nor listened to. Art is very marginalized. We are in a battle for self-esteem, but according to society we are only jokers. With our courage we aim for an artistic awareness to make art known to the population. It’s very complicated, but the only solution is work. Work with love and without politics.”

The lack of support and isolated position of Malian art also causes lack of confidence and even fear. Ibrahim: “look at the symbolism in our works, the fact that we are organized in collectives to reinforce ourselves. These are acts of resistance, a combat for solidarity.” Ange: “observing the problems and injustices that reign in our society, we intervene by proposing works, in order to criticize, raise awareness or even propose solutions.”

Tioye considers art as a way to better situations for the younger generation. “contributing to change is a generational duty, as a loyalty to former generations to take care of the next”. Seydou acknowledges this duty: ”photography should denounce and make reality visible. To see for those who cannot see and speak for those who cannot talk. We represent our generation and want to use our own eyes, tell our stories, display our references and propositions. We persevere, but we are not there yet.“

Future proof

In a society where the past and traditions value more than the future, I wonder how this generation of artists positions itself in the contradictory dynamics of societal values and global influences? I ask them as well what the world could learn from them.

Mariam: “I envision myself in my country, in an ambiance that is created by myself and my society. I believe very strongly in my ability to create a reality that incorporates art as a tool for cohesion. I am not that impressed by what is “international” but let’s discover and engage a more complete culture. I think Mali has everything to offer. In this culturally rich country, artists are very open, knowing how to share without condition. This makes us exemplary.”

Tioye affirms this ability to share, exchange and show solidarity. Seydou adds independence and the capability to live in a culturally diverse society: “we might need the world, but the world also needs us.” Ange proposes a bilateral exchange, but Ibrahim is slightly more critical, as he sees selfishness and ego as pitfalls that block progress and collaboration. But he is convinced that the Malian concept of collectiveness is exemplary for others to benefit.

Hama Goro is very confident in this generation, in which female artists slowly gain more visibility and independency. These collectives grow into a more internationally engaging group of creative entrepreneurs, combining art with many side jobs to survive. He advises them “to stay true to their own ideas and development, in exchange with their own culture and realities, but also deal with the realities outside Mali.”

On est ensemble: strategy for survival or sustainable attitude?

So, yes. The expression clearly fits these collectives, in urgent situations. But can collectiveness sustain their needs, when globalization inevitably marks its traces? How will these self-made learning systems affect future art production? How to research this concept of collectiveness, if art production is not considered a “member” of society? How to research art productions that represent thoughts and imagination that outside this society cannot be as easily understood? It requires interaction with different ways of experiencing art. It requires a critical reflection on methodology and process. It requires listening to the many stories and engaging being “ensemble.”