“Through history male artists have always objectified women. The work tries to subvert that, change that, challenge that. I am not necessarily looking at the men I draw as objects. The work is about taking away the process of objectification. Even though they are anonymous to me I eventually get to know them through the process of drawing, through scrutiny. It is important that the men are unknown to me and that they are anonymous.”

Yvette Greslé interviews Barbara Walker.

Barbara Walker: ‘sometimes work can exclude people’

Barbara Walker is an artist based in Birmingham. Her work explores histories of the human figure, portraiture, and the processes embedded in drawing. These concerns enter into a dialogue with social-political conditions related to masculinity, stereotyping, and the power relations of race and racial violence. Walker’s wall drawings of Black male figures (which she then washes away at the end of each exhibition) imagine visual strategies that counter the claims made by official historical-political narratives, media institutions, and the myths and prejudices that emerge from these. Walker’s work confronts systemic racism in the United Kingdom, overt and opaque (and its relationship to other historical-political-geographical conditions). Her practice, while political, is not didactic: rather her images, their internal lives (with their associated affects, contradictions and ambiguities) draw us into an experience that is not reducible to a singular perspective on the world. There is a political motivation to the work but also of importance is Walker’s imaginative and pragmatic relationship to drawing, and the research and visual interests that underpin the work.

Yvette Greslé: Tell me about your medium; and your particular relationship to drawing. What interests you about drawing?

Barbara Walker: Drawing is an accessible medium that is comfortable to work with. It’s very forgiving. It’s very flexible. It’s a medium that is easy to communicate with (and through).

YG: You appear to be especially interested in portraiture. You explore various visual languages and ways of representing the human figure. For example: your portraits might focus on the backs of heads. You also play close attention to fashion and things like jewellery and tattoos.

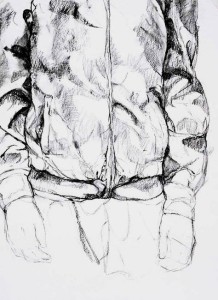

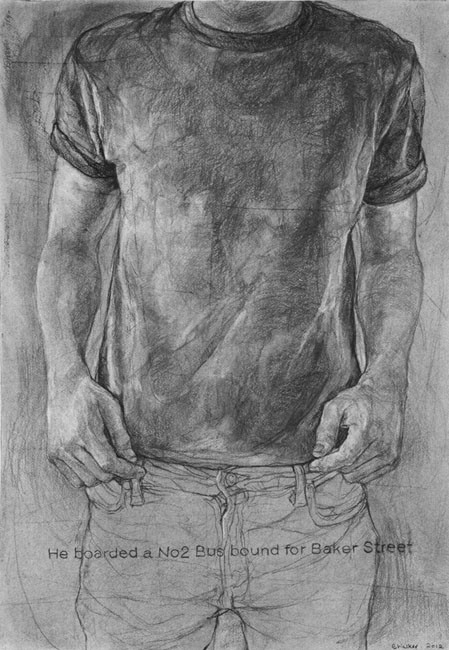

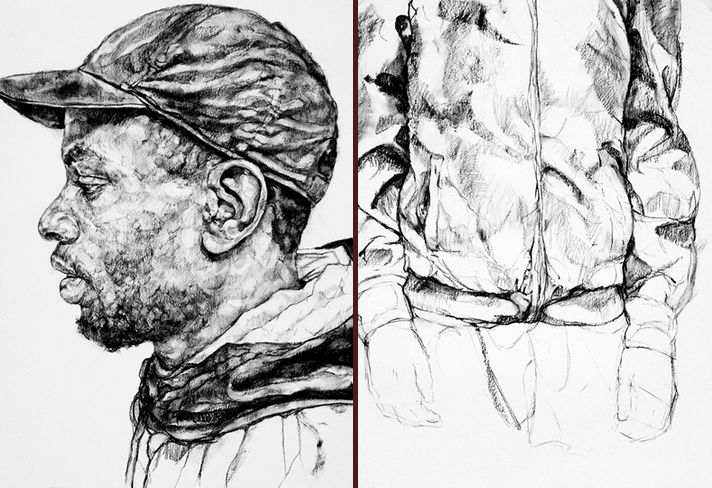

Show and Tell. The dichotomy of Sean, 2012 (photo: Tom Upton).

Show and Tell. The dichotomy of Sean, 2012 (photo: Tom Upton).

BW: I always have one foot in history and one foot in contemporary practice. I always go back to history. I do look back and re-enact history to go forward. I am influenced by certain periods of art history (and history and social history). I am fascinated by history. I have always been interested in history as well as in art: I always try to convey this through the work.

YG: How do you think of History as an artist?

BW: I was very focused on Giacometti in making some of the work. I am interested in his marks; his compositions; how he cuts into the drawing with charcoal. I am interested too in how he draws the viewer into the work. I am very fascinated by that and the use of charcoal as a material. Charcoal is so accessible. So fragile. It’s easy to apply and it doesn’t restrict you. It’s quite poetic. You can play with it and have fun with it. It’s not like painting. Painting is a different language. It can be very rigid and stiff and static. With drawing (or working within drawing) there is a looseness. There is freedom. Freedom to play and I love it for these qualities.

YG: When did you first encounter Giacometti’s work and think about its relevance to your practice?

BW: It was while I was studying on a Foundation Course. I looked at sculpture for a bit (Rodin, Giacometti). I looked at the physicality and materials. I looked at drawing and was really fascinated by the sketchbook. Giacometti really understood materials in terms of power and the formal information that was there. He thought about his use of the human figure within a space. There is a lot of movement in Giacometti’s drawing. There is a lot of rhythm and movement flowing through the composition. I love that sense of activity that seems to appear within the work.

YG: What do you think draws you to the human figure? The human figure is so much a part of your work and how you work with drawing.

BW: In visual art the figure is very important to me. Art can sometimes seem abstract, and hard for some people to connect with. I work with the human figure (and representationally) because of my interest in the audience. Working from the figure there is an immediate connection with the audience. Sometimes work can exclude people but the audience can connect with the figure. It’s human nature to want to relate and connect with something. I like that people can engage with the human figure in an immediate way and recognise it. A lot of the time we like to hold on to or connect with something. In working in this way the audience may see something or connect with something within that work and also with something within themselves. The figure is quite important to draw the audience in. It gives me something instantly recognizable with which to connect, especially if it is a human form. I think as humans we are always searching for ourselves in some way – the similarities and the differences – trying to gain insight into ourselves and others.

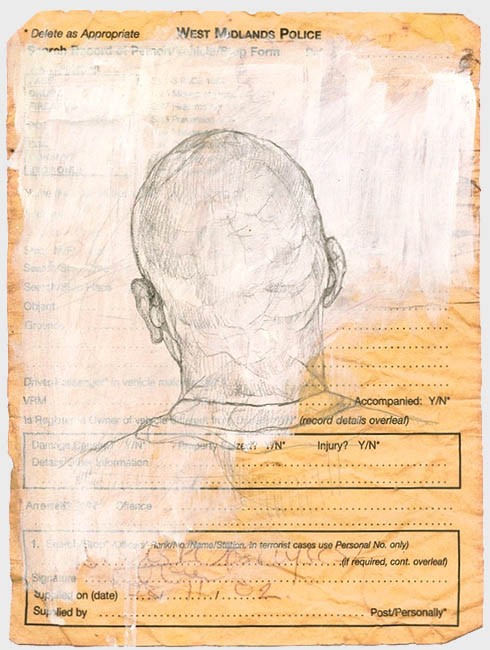

Louder than Words, My Song, 2006 (photo: Gary Girkham).

Louder than Words, My Song, 2006 (photo: Gary Girkham).

YG: You explore stereotypes, assumptions and perceptions (as they are inscribed in visual language). For example, you refer to the visual language of police mug shots.

BW: This goes back to my research. I went through police mug shots in archives at the Birmingham Library. I explored the idea of the mug shot and where the original is derived from. I looked at early portraiture in photography, and police photography: this was the impetus for this work. I do 6 months to a year of research before I even start. I need this as a foundation to test my hypotheses, to understand the subject matter that I’m dealing with. I want to make work that is considered. I need this foundation before I begin with the physical making of the product. The research is very important. I do think of myself as a research-based artist. I love research. I like going through archives. I am a scavenger of information. I also tap into popular culture, the internet, Facebook, social media, archives. I collect and gather conversation. There is not just one viewpoint.

YG: Empathy seems very present in your work.

BW: It’s always there. Empathy or looking at the human condition and trying to have some kind of understanding. There is a lot of emotion in the work.

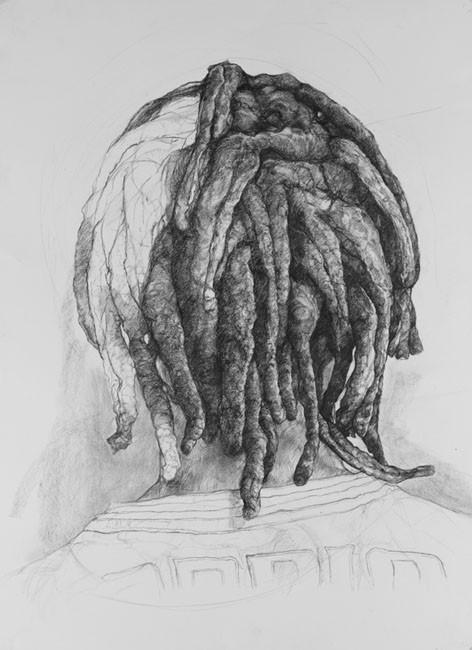

YG: Your work is very physical. I am thinking of the wall drawings in particular. I am struck by the physicality involved in making them (and in washing them away). What is the impetus for the wall drawings? They are interesting visually in a number of ways: the cropped faces, and their monumentality. They are ephemeral (the erasure). There is an element of performance to how you draw these figures onto the wall and then wash them out.

BW: These works came out of a residency at The New Art Gallery, Walsall, purely by accident. They came out of a body of work called ‘Show and Tell’ which is an ongoing project. I was given a studio that was very clean, very clinical, an intimidating white cube. It was a big space with a window. I immediately decided that my studio should be a gallery, a think tank, a space to have conversation. Initially I brought in existing work (as a strategy): work that was produced in 2008. But my natural response was to draw on the wall. I wanted to represent the visitors that would come into the space.

The individuals that appear on the walls are men that came into the space to see work. They were not drawn from my imagination. A lot of these men are men I don’t know. This was an opportunity to have a conversation with young men. For example: What do your clothes say about you? Do your clothes define you? Do you think about fashion? Why do you wear such and such item? From these conversations I began to develop a dialogue, record information while, at the same time, photographing these individuals. I then worked with photographs I took of the men, duplicating them on the wall. There are reasons why they are large: A lot of the work is about power and about belonging. ‘Show and Tell’ is about stereotyping and how people are judged, looked upon, or perceived through their clothing. The drawings look at portraiture and portraiture through different interpretations; through a different gaze, my gaze. I explore nuances, and subtleties, as much as possible. The work examines stereotyping. I am playing with perceptions (focusing on things like clothes).

Through history male artists have always objectified women. The work tries to subvert that, change that, challenge that. I am not necessarily looking at the men I draw as objects. The work is about taking away the process of objectification. Even though they are anonymous to me I eventually get to know them through the process of drawing, through scrutiny. It is important that the men are unknown to me and that they are anonymous.

Show and Tell. Finto, 2012.

Show and Tell. Finto, 2012.

YG: Is some of your work autobiographical? I am thinking about how you work with police ‘stop and search cards’ which belong to your son.

BW: These works are from ‘Louder than Words’. These works express an experience. My son has been stopped on many occasions. I started to gather the ‘stop and search’ cards and respond to these events as a parent and as an artist. And as an individual who wants to address issues that are happening today. A lot of my work looks at things that are happening in today’s society. There are historical references in my work but I am looking at what is happening today. These works are about race, stereotyping, identity, racial profiling. It is about home. It links to things that happen globally. It is looking at drawing.

YG: I was struck by how you draw over the bureaucratic language of the ‘stop and search ‘card. You draw over cards with graphite and so get smudgy marks. You have quite literally white-washed over one (the enlarged reproduction, at least) with white paint.

BW: I started to experiment and push my ideas in the series ‘Louder than Words’. There was a point in my practice where I started recognising that yes ‘I can paint and draw’ but what can I do with it? I was experimenting and not being too precious. It was more about the process. Not necessarily about the conclusion. This is why you get the mixture of materials. I always start with drawing. The ‘stop and search cards’ go through a process that begins when they are handed to my son. I collect them from him. I work with a designer, scan the card, print it out so that you get a first generation; maybe get a second generation. I will draw on to actual cards, scan them again. Or I will scan, enlarge and paint. I go large so that you can have access to them. You can get close to them and take in all the information they communicate.

Installation view, Djanogly Art Gallery, Nottingham (UK), 2013 (photo: Alan Fletscher).

Installation view, Djanogly Art Gallery, Nottingham (UK), 2013 (photo: Alan Fletscher).

YG: The ‘stop and search’ cards could just be thrown into the bin. But you confront them. They are to do with the bureaucratic language of the state and its profiling and categorisation of human bodies. It is traumatic for you as a mother; for any mother.

BW: It’s quite provocative because you get all these categories – this racial profiling – which is alienating. The work also looks at policing today; and it is quite traumatic and personal. It’s the most personal work I have produced to date. The gaze is not on me but there is that nurturing of that drawing on the wall because it’s my hands. I draw these figures and then I let them go. The scale is about power. It’s also about me and my relationship to visibility and inclusion. The work plays with ambiguity and layers. I usually start quite literally with drawing, charcoal drawing.

YG: How do you feel as you are erasing these figures? You invest so much in them; they are incredibly detailed. There is so much attention to proportion, the body, the clothing and then you wash them away.

BW: It does take a lot of strength. From the first mark on the wall I know the drawing is not permanent. I have already let go. But still in creating it I won’t cut corners, and the detail is very important. I also leave it for the audience to interpret it. I am interested in people looking at my work and bringing different perspectives to it. I love working large. The works are meant to be monumental. They are meant to stir and to have an impact.

YG: You are re-enacting loss over and over again through this work: the drawing and the erasure (the washing away) of these male figures.

BW: You are there but you are invisible, the invisible man. There is a reason why the drawings are removed. It’s a metaphor for how I see a lot of black men that have been removed from society. They are here for a bit but then they are removed. You see the traces and marks on the wall; those are the traces that are left behind. The removal is done by me or sometimes with the aid of others. It is a performance and it is documented. It’s a very emotional thing when you put so much feeling and time into it. I am using my whole body. I am just using charcoal. Nothing sophisticated, something accessible. I use a bucket of clean water to wash away each figure: sometimes there is more than one.

Louder than Words. Screen 1 & Untitled, 2006.

Louder than Words. Screen 1 & Untitled, 2006.

YG: The process reminds me of mourning rituals. The washing of the body of the dead. It also makes me think of what women go through in conditions of social and political violence. I am thinking of rituals of mourning and women’s weeping.

BW: A lot of emotion goes into this work. It comes back to ‘Louder than Words’ with my son. Although it was happening to him it was also happening to me. When I begin to make the work I have already said goodbye to it. Although there is a contradiction in my process, and a ritual that I go through. When I get to the point of erasing the work I will have to look at it for a while, spiritually take it in, take it in with my eyes, say goodbye, and once I’ve done that I let it go.

For more about Barbara Walker see her website www.barabarawalker.co.uk

Courtesy: the artist.