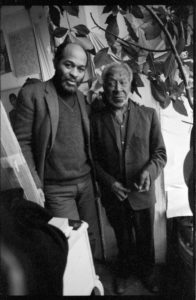

In 1975, photographer Marion Kalter grabs her camera and immortalizes the very moment that would trigger the desire to write this text. The crime scene takes place in Paris in Beauford Delaney’s studio located in rue Vercingétorix, Delaney and Ted Joans standing next to each other. Both of them were painters, and Joans was also a Surrealist as well as a jazz musician and poet. When looking at this picture in the 21st century, it is almost impossible to guess the many threads and double visions related to painting and music, jazz and poetry. Unless you start digging more.

Karima Boudou digs into the relation between the African-American artists Beauford Delaney and Ted Joans

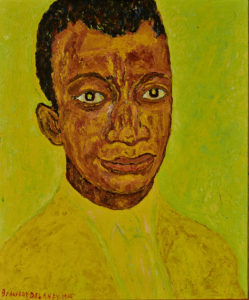

Beauford Delaney, James Baldwin, 1965, courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York

Double Vision: Beauford Delaney and Ted Joans in France.

“I remember standing on a street corner with the black painter Beauford Delaney down in the Village, waiting for the light to change, and he pointed down and said, “Look.” I looked and all I saw was water. And he said, “Look again,” which I did, and I saw oil on the water and the city reflected in the puddle. It was a great revelation to me. I can’t explain it. He taught me how to see, and to trust what I saw. Painters have often taught writers how to see. And once you’ve had that experience, you see differently.” (1)

James Baldwin

“I can’t go home because I never really left …

I sailed to France sixteen years ago, but I’ve never left America.

The body goes somewhere, that’s all …” (2)

Beauford Delaney

“Jazz is my religion and surrealism my point of view. Jazz is the most democratic art form on the face of earth; it’s a surreal music, a surreality. Surrealism like jazz is not a style; it’s not a dogmatic approach to the arts like cubism. Poetically I’m first of all concerned with sound and rhythm. It is not so much the word, but the wording itself because of the way we black people handle words. Duke Ellington said “It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing”. It GOT to swing! I can write a jazz poem about any subject, and most of my jazz poems are written about things I love, and things I hate, and things I associate. But jazz poetry is not lyrics: when you built your poetry on a composition, then you have boxed yourself in, same with rehearsing, ‘cos each time I read a poem it will be different. I do not change the words, it will be the sound and the rhythm and the whole atmosphere.” (3)

Ted Joans

Ted Joans with Beauford Delaney in his studio, Paris, 1975. Photograph courtesy of Marion Kalter.

In 1975, photographer Marion Kalter grabs her camera and immortalizes the very moment that would trigger the desire to write this text. The crime scene takes place in Paris in Beauford Delaney’s studio located in rue Vercingétorix, Delaney and Ted Joans standing next to each other. Both of them were painters, and Joans was also a Surrealist as well as a jazz musician and poet. When looking at this picture in the 21st century, it is almost impossible to guess the many threads and double visions related to painting and music, jazz and poetry. Unless you start digging more.

Beauford Delaney was born in 1901 in Knoxville. In 1923, he leaves rural Tennessee for Boston where he studies in several art schools and discovers in museums in Boston and Cambridge the work of Paul Cézanne, Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. In the late 1920’s the artist moves to New York during the last developments of the Harlem Renaissance. He was a close friend of several artists and writers such as Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, Willem de Kooning, Louis Armstrong, James Baldwin and Henry Miller. From these friendships he painted many portraits of William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, Ella Fitzgerald, James Baldwin, Marian Anderson and Duke Ellington. In 1945, Henry Miller writes the essay The Amazing and Invariable Beauford Delaney. In this text, Miller tells the story of his visit to Beauford Delaney’s Greene Street studio in New York during the evening. Miller’s impressions about Delaney’s paintings rely on an experience of an artistic production saturated with colors and light. The small paintings Miller witnessed depict street scenes in the surroundings of the artist’s studio. The same year, Delaney paints several portraits of James Baldwin and Miller. A queer artist and a major figure of the Harlem Renaissance, his artistic production spans from the 1930’s to the 1970’s. It is characterized by a variety of styles; from figurative urban scenes in Harlem to portraits, as well as abstract paintings. Delaney’s first solo exhibition opens in 1930 at the Harlem Library in New York.

Alongside several African American artists and writers from his time, he traveled to Paris after World War II in 1953 on the SS Liberté, from New York to Le Havre with painters Herbert Gentry (1912-2003) and Larry Potter (1925-1966). Since 1956, his work has been introduced to the French context with several solo exhibitions in Paris, mostly in commercial galleries such as Galerie Prisme (1956), Galerie Facchetti (1960), Galerie Lambert (1965) and Galerie Darthea Speyer (1973 and 1992). Despite this, he found little commercial success in France and lived mostly from the support of friends and patrons. In addition, historical exhibitions of the artist in France also include the Centre Culturel Américain (1961 and 1969, Paris), the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts; as well as a participation in the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles (1954, 1960 and 1963, Paris). In 1967, Delaney participates in the group exhibition L’Âge du Jazz at Musée Galliera in Paris. In his works from that period in France, Delaney introduces a specific take on the use of light, a distant echo to the work of Impressionists. Impressionism during its developments has been characterized by two dynamics, first the movement was the manifestation of a liberation from artistic movements from the past; and then this phase was followed by a time of reconciliation. Delaney was inspired by the movement but seemed to approach it as a source of inspiration rather than as a tool of assimilation to Western art historical categories. A colorist, Delaney was during the last years of his career an abstract painter, by going back and forth in his work from a figurative expressionism to a colorful abstraction, vice-versa. Delaney lived for a while in Clamart, a suburb of Paris. This precarious lifestyle as well as alcohol led him to be admitted at Hôpital Sainte-Anne in Paris where he died in 1979. James Baldwin and other friends paid for his burial in the Thiais cemetery in the Val-de-Marne department. A year before his death, in 1979, the Studio Museum in Harlem organized an important retrospective of his work.

Ted Joans, whose original name was Theodore Jones was born in 1928 in Cairo, Illinois. He went to Memphis at the age of twelve and received a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Indiana University in the early 1950’s. After graduating Joans moves to New York City where he becomes connected to the art scene in Greenwich Village, the Beat movement as well as to the jazz poetry scene. His first books, Beat Poems and Funky Jazz Poems are published respectively in 1957 and 1959. They are part of a larger corpus of around thirty collections of poetry, which Joans often read with music related to his passion for avant-garde jazz. In his writings he denounced injustice, racism and sexual repression. From the 1960’s, Ted Joans starts travelling the world, later settling in Tangier, Morocco and then Timbuktu, Mali. During those years, he continued writing poetry and painting. Some of his experiences in Africa are reflected in the poems Afrodisia: New Poems (1971). He also contributed to Présence Africaine, Black World, Coda and Jazz. During the last years of his life, Joans lived in Vancouver with his partner Laura Corsiglia, where he continued to write until his death in 2003. An African American Surrealist, painter as well as a jazz musician and poet, he often illustrated his poems with surrealist collages. Joans’ work is a mélange of several avant-garde streams and he can be seen as the precursor to the orality of the spoken word movement. In the 1960’s, Joans meets André Breton in Paris. Alongside the Surrealists, Joans was interested in the exploration of the solitude of dreams, unconsciousness, love, as well as advocating for collective action and social protest. Surrealism appeared after the First World War, as a reaction to the demise of traditional societal and institutional structures after 1919, which the movement wanted to respond to. The movement was founded by André Breton (1896-1966) who explicated the philosophy and goals of the movement in the First Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924, followed by the Second Manifesto of Surrealism in 1929. The original group was composed of French poets Aragon, Desnos, Éluard, Péret, Soupault as well as German poet Max Ernst. Beyond its intellectual and literary beginnings, the movement extended to visual arts by becoming an international movement with the American Man Ray, the Italian Chirico, the Spaniards Miro and Dali, the Belgian Magritte, the Romanian Victor Brauner, and the Chilean Matta, amongst others. In dialogue with the Surrealists, Ted Joans explored in his work a spirit of adventure and free imagination, a dynamic initially initiated by André Breton and his friends. He was deeply influenced by Surrealism as a literary and artistic movement, driven by latent underground forces which were discovered and released between 1919 and 1939. In 1996, Ted Joans writes an autobiography entitled Je Me Vois (I See Myself) (4) and dedicated to another Surrealist, Joseph Cornell.

‘POEME’ is an example of a language-game Ted Joans was familiar to. Composed by André Breton in 1924, it is made of pasted fragments of articles and newspaper headlines Breton would assemble in the rue Fontaine. Breton’s archive contains several school exercise books belonging to Jacques Baron, Max Morise and Simone Kahn which are similar collage-poems made of ready-made phrases. In that perspective, Joans and the Surrealists’ interest in words (often in their pre-formed aspects) derives from Jean Paulhan’s work on proverbs and clichés. Paulhan was interested in proverbs as fixed linguistic units, and in the possibility of reactivating the signifier by revitalizing meanings via strategies of defamiliarization.

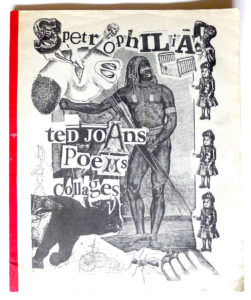

(left)André Breton, ‘POEME’ (c. 1924). Pasted typographical elements, 21 x 17. Private collection, Paris. André Breton, Je vois, j’imagine, Paris: Gallimard, 1991, p. 145. (right) Cover of the publication Spetrophilia. Ted Joans, Poems, Collages. Publication produced by Laurens Vancrevel, Amsterdam: Amsterdamsch Litterair Café ‘De Engelbewaarder’, 1973.

In 1973, the Amsterdamsch Litterair Café ‘De Engelbewaarder’ publishes Spetrophilia. Ted Joans, Poems, Collages. Joans’ collage on the cover page displays the literal cutting and pasting process which determined its composition: fragments are made up of images from different sources as well as words in different typefaces which were pasted onto a page. Joans’ layout is informed by techniques characteristic of newspaper headlines and advertisements, such as different typefaces, a more or less centered text. The typographical and visual strategies used by Joans are less rudimentary than Breton’s. Joans interest in wording goes beyond the limited use of roman and italic types, boldface and capitalization. He attempts to display the mode of fabrication of his surrealist imaginary through the appearance of each fragment presented primarily as a visual sign. The cover page of Spetrophilia. Ted Joans, Poems, Collages presents different typefaces and visual fragments, and the isolation of each of them – underscoring the discrete quality of each fragment and spatializing the text – makes the reader apprehend the work firstly as a material reality, a spatial, rather than linguistic, unit. The poetic is awakened through the transformation of the banal in a metaphorical and metonymical sense. The program of Surrealism, therefore, demanded a new literary and visual language commensurate with the demands of external and fragmentary manifestations of a more significant whole.

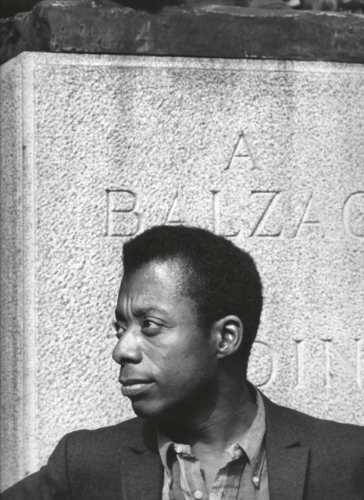

In seeking to understand “this greater world” and to find a means for visually expressing it, Beauford Delaney explored a whole host of new ideas and art forms, from color to light, all of which undermined and challenged the authority of Western positivism and traditional values in the arts. During his training in Boston, Delaney was aware around him of art produced according to academic standards. Some of the paintings most indicative of Delaney’s work in France demonstrate a thematic and stylistic consistency, they include L’église de Saint-Germain-des-Prés which he painted in 1971. A year later he paints La statue de Balzac par Rodin as well as Yellow Cypress, a painting he made when visiting James Baldwin in Saint-Paul-de-Vence in the South of France.

James Baldwin below Auguste Rodin’s Statue of Honoré de Balzac, at the crossing of the boulevards Montparnasse and Raspail, Paris, 1960. Photography by Sam Shaw (c) Sam Shaw Inc. courtesy Shaw Family Archives, Ltd.

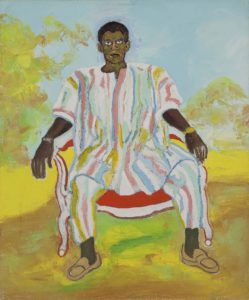

The decades he spent in Europe are characterized by a saturated and limited palette. He executed numerous pastels, portraits with bright colors in which psychology and atmosphere are formally perceived via colors and light. He shunned trompe l’oeil or other illusionistic devices in an effort to produce images that are technically more honest, capable of greater expressive force, charged with spiritual significance, and offering a much-expanded view of life. Retrospectively, it is clear that those intellectually intense and productive years in France marked an important period of formal experimentation and philosophical investigation that eventually resulted in a synthesis between form and content. An art which introduced him to a new way of understanding and examining the world about himself. The viewer notices an increasingly more radical obfuscation of a clear, linear, prosaic or mimetic representation of the world. In that perspective Delaney’s artworks represent a break from the material representation and interpretation of the world – whether the represented world be material or spiritual – to a more spiritual interpretation and understanding of the world, by depicting what lay behind empirical observations. Delaney is not only in love with visible nature; he is also a dreamer, an imaginative painter. A Delaney painting is a poem rather than a picture. It portrays an emotion called up by a scene, and not the scene itself in all its elaborate complexity. It undertakes to give only so much of it as is vital to that particular feeling, and intentionally omits all irrelevant details, such as in the painting Man in African Dress (1972).

Beauford Delaney (1901-1979), Man in African Dress, c.1972, oil on canvas, 21 3/4″ x 17 3/4″ / 55.2 x 45.1 cm, signed; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

It is the expression caught from a glimpse of the soul of nature by the soul of the artist. To understand his paintings, it is from this standpoint they should be regarded; not as soulless photographs of scenery, but as poetic presentations of the spirit of the scenes. This perception of reality as a state of constant fluctuation informs much of Delaney’s oeuvre. The more one looks at Delaney’s artworks, the more things begin to happen. If you spend time in front of a Delaney painting and watch, figures and objects come in and out of focus, just as if everything in the world is elusive. The reason for this ambiguity in Delaney’s work is that a Delaney painting is not simply a depiction of a new way of seeing; it is, rather, the visual articulation of a metaphysical state. His art embodies another conception of reality as opposed to a Western, rationalized conception of reality. In general, Western philosophy originates and perpetuates itself in a world of duality, in the subjectivity of an individual’s mind judging the empirical world and reason. Western thought always refers to human reason. In Delaney’s oeuvre, being and non-being mutually coalesce and seem to perpetually contradict themselves, and through this mutual and perpetual contradiction they can attain an absolute actuality, understood as a continuum, that exists within this perpetual play. In his late paintings, Delaney knows how to make a virtue of emptiness, how to keep a great expense of the picture surface intensely meaningful without any resort to picture-filling incident, by gradually recognizing the power of abstraction. In a great deal of the paintings Delaney produced while he was living in France, he regularly organized space in a sequence of vertically oriented, rectangular divisions, which he then flattened out across the surface and unified with color. This formal feature, a leitmotif of Delaney’s style, can be seen as an invisible skeleton, an imaginary structure of loose and connected sequences which function as an abstract basis of all of Delaney’s compositions. To this he marries his unique way of manipulating the viewer’s perception of objects and spaces through color relationships, varied brushwork and patterning. This resulted in his quest to articulate the Absolute, a state of flux between presence and absence, being and non-being. It is the recurrent theme, an idée fixe, informing much of his work and one that he constantly sought to find inventive means of communicating. That is maybe the secret both Ted Joans and Beauford Delaney whisper in Marion Kalter’s photograph in Beauford Delaney’s French studio.