Black Modernism was a development that was finding a home for itself in contemporary white culture. Not only did it stimulate wonderful movements like the Harlem Renaissance, it exposed society to black experience and the shortcomings in black rights. As an artistic expression Black Modernism continues to develop and by doing so creates contemporary expression for a new generation.

Christabel Johanson on Black Modernism

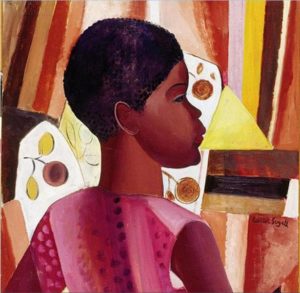

Laser Segall, Perfil de Zulmira, 1928.

Black Modernism

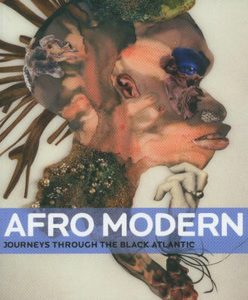

In 2010 the Tate Liverpool hosted Afro Modern: Journeys Through the Black Atlantic. Inspired by Paul Gilroy’s book The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (1993), the exhibition focused on the culture formed between Africa, the Caribbean, Europe and North & South America. The exhibit was the first to explore the extent at which this hybrid culture affected Modernist art, as well as charting how black cultural figures helped shape twentieth century Modernism up until the present day.

Ten years on from the exhibition, the ripples created by this hybridisation are still being felt in the modern world. African and Caribbean art, artists and aesthetic styles are still shaping society from musical genres, fashion, to trends within the art industry. Black Modernism is the expression of intersectional interactions of black people across geographies from the homelands through to cosmopolitan spaces. With history there is a cyclical rejuvenation of interest and to trace the roots of this inspiration we look back to the turn of the twentieth century.

*

Pablo Picasso received inspiration from many non-European influences. His 1909 sculpture Bust of a Woman shows clear influence from African tribal art. The bust was of his mistress at the time; Marie-Thérèse Walter. The piece has Picasso’s signature style alongside the tribal mask-like features of Marie-Thérèse’s face. The figure is composed of plaster with the nose represents Picasso’s penis. This also connects it with the phallo-centric models of African tribal art.

Bust of a Woman (Marie-Thérèse), 1909

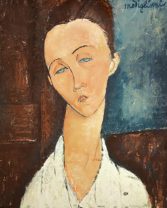

Black aesthetics inspired other white artists such as Amedeo Modigliani whose sculptures and paintings emphasised curves in a sensual way. This echoed the fuller figures depicted in African carvings which denoted sexuality and fertility.

Amedeo Modigliani, Portret van Lunia Czechowska, 1918, private collection

Negrophilia was a craze that swept 1920s Paris with bohemians and avant-garde artists typically collecting African memorabilia, listening to black music and buying black art. It was fashionable and seen as a sign of coolness. This obsession with black culture derived from an interest in “primitivism”, as artists living in a post-war era were now interested in a simpler way life stripped back from contemporary technology and lifestyles.

*

The 1920s was a notable decade for the expansion of black culture into everyday consciousness. Within that period the Harlem Renaissance exploded in popularity. It centred around Harlem in New York and was known as the New Negro Movement focusing around black artistic, intellectual and cultural affairs. There was cross-fertilisation between the Parisien Negrophilia and the Harlem Renaissance as many French speakers in Harlem were influenced by it. It was considered a restart of black artistic interest and invigorated the scene.

*

Within the neighbourhood Aaron Douglas became known as the Father of Black American Art and was an important figure within the Harlem Renaissance. He was a painter and artist and had illustrated The New Negro, a book compiled by Alain Locke on which the New Negro Movement name was based. Douglas landed in Harlem from Kansas in 1925 and immersed himself in the neighborhood. He sent his illustrations to black-centric magazines including Opportunity; the magazine outlet of the National Urban League and The Crisis which came from the National Association for the Advancement Colored People. He was one of the first African Americans to depict racial themes in modern art.

Speaking on Harlem Douglas said, “There are so many things that I had seen for the first time, so many impressions I was getting. One was that of seeing a big city that was entirely black, from beginning to end you were impressed by the fact that black people were in charge of things and here was a black city and here was a situation that was eventually to be the center for the great in American Culture”.

Aaron Douglas by Betsy Graves Reyneau

Harlem and modernism were becoming one and the same which led to other emergences like the Jazz Age. Douglas’ style combined African art and Modernism along with different modern expressions like Art Deco. The results were striking bold pieces which often used silhouettes. Of course the nature of a silhouette is a blacked out shape which complemented the subjects themselves who were mostly black people.

Aaron Douglas, Charleston, gouache and pencil on paper board, ca. 1928

Douglas submitted Charleston with other illustrations for a series of short stories by Paul Morand which dealt with the relationships and situations black people dealt with in the wider world. The story of Charleston is about a white women whose fear of black men ends with the murder of a black saxophone player. The gnarled fingers and the presence of the lynch rope hint at the violence amidst the female figure and the saxophonist. The style evokes Art Deco, whilst the rays of light and circular patterns section off the image thus intensifying the picture.

*

Another key piece by Douglas is Study for Aspects of Negro Life: An Idyll of the Deep South (1934). This was a gouache – a form of watercolour painting – in which Douglas borrowed from European Cubism as well as African art. Within the span of the imagery Douglas covers labour on the fields/plantations, suffering of black people, music and revelry. The figures at the back may be holding hands in prayer or celebration.

Study for Aspects of Negro Life: An Idyll of the Deep South, 1934, Tempera on paper,Collection of David C. and Thelma Driskell

Thematically similar is Lasar Segall’s Banana Grove (1927). Segall was a a Lithuanian Jewish and Brazilian sculptor, painter and engraver who used modernist, impressionist and expressionist styles to portray human suffering in its forms from prostitution to persecution (1891-1957).

Lasar Segall, Banana Grove (1927), Oil on canvas

In Banana Grove (also known as Banana Plantation) Segall places a lone black figure amongst the vertical leaves of a banana plantation in Brazil. The scene is dense but the audience’s attention is drawn to the central figure and focuses its meaning more intensely. Segall is commenting on slavery and the isolation of black people within it.

*

Chris Ofili’s work belongs to a group known as “post-black art”. Born in 1968 in Manchester, Ofili is a Turner Prize winner who is best known for his paintings. His work examines historical as well as modern black narratives. The work has a “punk” feel to it using glitter, manure, paint and pornographic magazine cuttings to visualise his subjects.

The Holy Virgin Mary, 1996, courtesy the artist and David Zwirner Gallery New York

Calling forth the sexualised imagery of the black female form, Ofili subverts the subject-matter here by figuring the Virgin Mary as a black woman. He states “When I go to the National Gallery and see paintings of the Virgin Mary, I see how sexually charged they are.” With a radiant warm backdrop which evokes traditional gold-leaf encrusted paintings the viewer is lured into a false safety. If one looks closer at the cherubs which surround the woman, we see they are made from pornographic magazine cuttings. Ofili says his interpretation of Mary is the “hip-hop version”. This is a handy term which conflates a black-centric perspective onto traditional imagery.

Isaac Julien, Western Union Series No. 1 (Cast No Shadow), 2007, courtesy Victoria Miro and the artist

With all the examples listed, what is important throughout the years is that different elements drew together and shaped the aesthetic and visual language of Black Modernism. From European to transatlantic influences, from trends to historical events, Black Modernism was a development that was finding a home for itself in contemporary white culture. Not only did it stimulate wonderful movements like the Harlem Renaissance, it exposed society to black experience and the shortcomings in black rights. As an artistic expression Black Modernism continues to develop and by doing so creates contemporary expression for a new generation.