This is the last article in a series of articles on the friendship between ‘two’ African American artists, a “friendship beyond understanding”. In every article The Harlem Renaissance is the context of the story. This article is about the friendship between the poet and novelist Claude McKay and the activist poet Charles Ashleigh.

Rob Perrée tries to answer the questions the friendship evokes.

Portrait of a friendship 6

CLAUDE McKAY AND CHARLES ASHLEIGH

Langston Hughes, the most important poet of the Harlem Renaissance, writes in 1925: “You are still the best of the colored poets and probably will be for the next century and for me you are the one and only.” Colleague James Weldon Johnson calls his collection of poetry Harlem Shadows “… .one of the great forces in bringing about …… the Negro literary Renaissance.” An artist does not need much more compliments to conquer a place in history. You would think.

It did not happen.

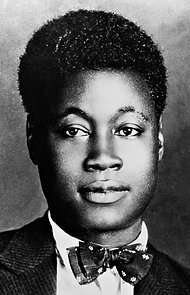

(Unknown photographer)

Claude McKay receives little or no attention in most publications about the Harlem Renaissance. In the Signifying Monkey. A Theory of African American Literary Criticism, the standard work of Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates, he does not appear at all.

It is possible that – out of sight – he disappeared from attention because immediately after the publication of his first American collection of poetry – in 1922 – he left Harlem to travel. He does not return until 1934. I do not think that absence was a decisive factor. A comment from Alain Locke implicitly indicates two other more important factors. The New Negro theorist calls him “The shameless playboy of the Harlem Renaissance“. An unflattering comment that touches on McKay’s way of life and political views.

Courtesy: Penguin-Random House, edition 2020

Claude McKay was born in Jamaica in 1889, in the Clarendon Parish. He mostly grew up with his brother. He is a teacher and introduces Claude to both British and classical literature. The story goes that little Claude was already writing poems at the age of 10. In 1907 he meets Walter Jekyll, an ex-clergyman, originally British but moved to Jamaica to become a planter, who is mainly concerned with collecting traditional local stories and songs. He recognizes McKay’s talent and mediates in the publication of Songs of Jamaica (1912). This expresses his sympathy for the black working class. McKay will receive a literary prize for this and his next collection.

With the money associated with that prize, he leaves for the US to continue his education. He first enrolls at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. He is shocked by the racism in the South. That would influence his literary work. Because he finds the training too militaristic, he completes his education at Kansas State University. In 1914 he moves to New York and marries a childhood friend.

Courtesy: Northeastern University Press, edition 1987

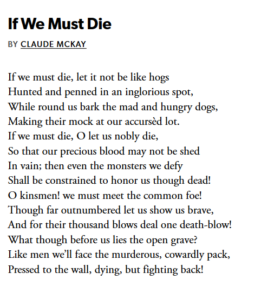

Since he cared already about the fate of the black worker when he was living in Jamaica, his stay in the South of the US served to catalyze his involvement with the cause. He develops sympathy for communism, becomes editor of the Marxist magazine Liberator and interviews Trotsky. During this period he wrote the poem that would become his best known: If We Must Die. Race riots in Harlem are the reason. The sonnet is widely regarded as the first Harlem Renaissance poem. McKay himself says: “…… The Negro people unanimously hailed me as a poet.” But his left-wing radicalization does not appeal to everyone. The Harlem Renaissance is not a worker movement, rather an intellectual, middle-class movement. Moreover, from a national perspective, there is no greater enemy for Americans than the communist. The fear of the red danger is still very much alive. That the FBI – the institutionalization of that fear – is going to interfere with the poet should therefore hardly come as a surprise. McKay decides to leave the country.

During these years, the second major barrier to his fame and acceptance arises: he starts dating men. Often, often briefly, and often from his own literary circles: the critic Waldo Frank and the poet Edwin Arlington Robinson, for example. His travels to Russia will not have satisfied that need, but in Paris and Morocco he will have every opportunity to put his homosexuality into practice. In Tangier he is part of the decadent international community of writers and artists who celebrate freedom inspired by the exotic environment. Paul Bowles is one of them. In a letter he claims that he had to resist McKay’s advances. However, it is because of his political views that McKay clashes with the authorities there and is forced to leave the country. Regrettable. He says about Tangier in his biography: “For the first time in my life I felt my-self singularly free of color-consciousness”.

The Harlem Renaissance may have allowed for a lot of free behavior, but openly speaking out for a “different” orientation is not standard for everyone. The nickname Shameless Playboy used by Locke (homosexual himself) says enough in this context.

Courtesy: Charles Kerr edition, 2004

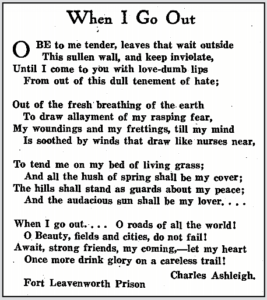

Charles Ashleigh, Class War Prisoners Poem, 1920/Leavenworth Prison, 1918 (unknown photographer)

In his traveling years he has an on-again-off-again relationship with the Briton Charles Ashleigh (1888 or 1889-1974), a writer and translator who shares McKay’s political views. McKay gradually started to think like a communist. Ashleigh was ‘born communist’, as it were: he is a full-blooded, campaigning communist. He comes from a working class environment and (thus) cares about the fate of the worker. This was demonstrated by not being averse to worker jobs, by organizing strikes, but also by writing for newspapers and writing poems. There is no doubt about his sexuality: he openly professes his homosexuality. On his journey through the Americas, he meets Claude McKay. They remain friends until McKay returns to New York. In 1944 he left his radical political ideas behind and converted to Catholicism. He dies four years later.

Courtesy: Penguin-Random House, edition 2020

A few months ago a previously unpublished McKay novel came out: Romance in Marseille. The text on the back probably proves why the book has not been published before: “Romance in Marseille traces the adventures of a rowdy troupe of dockworkers, prostitutes, and political organizers – collectively straight and queer, disabled and able-bodied, African, European, Caribbean and American. “

Courtesy: Harper & Brothers, edition 1933

During his years in Paris McKay writes 3 novels. Home to Harlem (1928) becomes a bestseller. Banjo: A Story without a Plot (1929) is less successful. Banana Bottom (1933) also failed to reach the high circulation of his first novel. All three are very readable books that, partly due to their gender theme, are still topical. The covers of the first editions were designed by the artist Aaron Douglas.

In 1937 he writes his biography: A Long Way From Home. It describes, among other things, his more complicated relationship with the Harlem Renaissance: belonging in terms of content but also fleeing from it. The reader gets a good idea of the problems that a black man with clear views and a different lifestyle experiences. Especially the part about his stay in Tangier makes it clear why he needed freedom in order to develop fully, as a person and as an artist.