Being in post-colonial society there is a narrative of identity that was placed upon you. It’s as though you’re expected to play a role – you’ve been given a script and you’re doing your best to play into this idea and deliver this character. As a woman you are striving to live up to the standard of Eurocentric women, a standard that’s difficult for even some European women.

Christabel Johanson on Cydne Jasmin Coleby

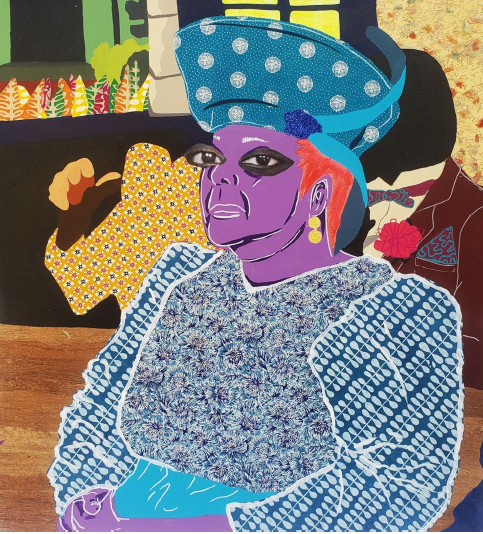

I’ve been made whole, 2020

Cydne Jasmin Coleby:

Queen Mudda

Queen Mudda is Coleby’s first solo exhibition at Unit London. Bringing both the flavour of Baroque and the Bahamas, she delves into ideas of matriarchy whilst celebrating women as the backbone of family lines.

As she prepares for her debut we caught up to discuss womanhood, the male gaze and courtly aesthetics.

Crowning Ceremony, 2021

Tell us how you started your career and evolved as an artist?

I initially started my fine art degree at The College (now University) of the Bahamas but I was unable to finish due to financial constraints. From there I worked odd jobs, volunteering at art spaces, as well as taking on small freelance graphic design projects as a way to build my design and computer skills. Eventually I was able to land full-time design jobs in various creative spaces, while maintaining my freelance practice. I solely did this for about 6 years before I picked up a paintbrush again in 2018. It was that year that, with the encouragement of one of my art idols, Kendra Frorup, I submitted a proposal for the Ninth National Exhibition at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas. This was where I debuted works from my God Called Self series. The works caught the eyes of art advisor/curator Maria Brito, as well as international curator Larry Ossei-Mensah, and with their promotion, my work gained attention from other international gallerists and curators.

As for my style, I’d say it’s an amalgamation of all of the things I’ve learned over the years, in my studio art classes, as well as my years of working as a graphic/digital designer. I’ve always had love and fascination with deconstructing and reconstructing the figure, as well as mixing and layering materials. I experimented a lot of with this in the early days of my practice. Now, having worked a designer for so many year, my process beings in the digital space and this allows me to problem solve in a more thoughtful way, and think that shows in the final product.

Who do you credit as an inspiration?

I have so many because I’ve been fortunate enough to have personally known professional artists for most of my life. So I’ll go through the ones who’ve have a direct impact my practices. My first artist inspirations go back to my childhood days, with Stan and (the late) Jackson Burnside. They were the first examples of working artists – sure they had other jobs to support their crafts, but they were he first persons to show me that there were creative fields out there. My next source of inspiration came from Sonia Isaacs. I attended her after-school art program and it’s with her I really honed in my understanding composition and my sense of colour. From them there went on to the College (now University) of the Bahamas, where I met John Cox and Heino Schmid. I have an admiration for all of my art professors at this time, but these two provided me with the most invaluable art lessons. Heino helped to shape my art process, encouraging the notions of juxtaposition and dispelling the myths of being truly original. He also was the first person to show me how to do anything on Photoshop, which is now an invaluable resource to practice. John Cox challenged my creative thinking and encouraged rigor and exploration in my practice.

Courted Laydees, 2021

The show mentions “the performance of womanhood, of respectability, of being.” I suppose the lens of performance could be seen in relation to males, to society and to other females. Could you elaborate more on this?

Being in post-colonial society there is a narrative of identity that was placed upon you. It’s as though you’re expected to play a role – you’ve been given a script and you’re doing your best to play into this idea and deliver this character. As a woman you are striving to live up to the standard of Eurocentric women, a standard that’s difficult for even some European women. As woman of African descent it’s even more so a performative act to live up to this standard. The ways in which we would naturally present ourselves have been deemed immoral. Black women within these spaces have historically been hyper-sexualized, brutalized and demonized for the simple act of being. So to discredit these stigmas, respectability comes in to play. You find women who’ll diminish themselves to be seen as having propriety, while those bold enough to live in their truths are vilified.

Was there a particular person or incident that was the catalyst for creating this show?

It was a photo of my mother and her cousin Annette, as they were getting ready for Annette’s wedding. My mother and her cousin have a sisterly relationship. Throughout their lives I’ve seen them support each other through some of their most critical moments, in some cases in replace of the men that once claimed to support them. It’s this relationship that encouraged me to shift my gaze to my family as a whole.

Even while producing the show I was reminded of the solidarity of the women in my family. Seeing first-hand how they/we do the thankless work required to maintain, and support our families, made the need of this exhibition more apparent for me.

I love the theme of celebrating Matriarchy. It is an important message. How do you think Patriarchy has wounded females over time?

I think the biggest wound the Patriarchy had on the female populous was through its objectification of women. It reduced women to being objects of servitude towards their male counterpart. It sought to remove our agency and autonomy, while also putting unscrupulous expectations on who/what we were. When a person is reduced to a tool their value is directly connected to how well they perform the intended function. Once a woman is incapable of doing “women’s work” such as childbearing, home maintenance, upholding societal standards of beauty her value decreases. And as we see the world changing, some of the things that were expected only of men are now expected of women, without reducing the original unrealistic expectations originally placed on women. Regardless of the strides women make within their respected fields, the narrative always circles back to archaic standards of their value – their beauty, their mothering capabilities, their romantic linkage to other men (sometimes regardless of their sexual orientation).

However times are changing, and we’re seeing an increasing amount of women and men advocating for end to these patriarchal standards.

Church Mudda, 2021

The exhibition can be read as a politicized piece. How do you understand balancing the dichotomy between the Matriarchy and Patriarchy? Is there an “end goal” where both are united?

There isn’t anything inherently wrong, with any gender being in a ruling/governing class of a society. Issues present themselves when a particular sex is seen as the standard and therefore creates restrictions that prevent the opposite sex from upholding positions of power. This goes for both the Patriarchy and Matriarchy. There are more examples of this in world history within patriarchal cultures, but that doesn’t have to be the case. It truly boils down to what societies of those times allowed and ultimately normalized. In 2021 we’re starting to normalize equality. The pace at which cultures have these conversations vary but with global access provided by the internet, these conversations no longer have to happen in vacuums. We’re also getting to a place of (re)normalizing multiple gender identities and as we move away from binary constructs, the concepts of a matriarchal and patriarchal governance will be obsolete or are at least blurred.

Takes a Village, 2020/F Hands, 2020

I see the exhibit as an opportunity for males to celebrate women. How do you think men in your audience will feel about your work?

From my personal experience, men love my work. In my communities there is a lot of love and respect for female elders and mothers. In the Bahamas though the governance and laws, tend to favour the male citizens there is the social understanding of women being the building block and foundation of society. Sadly you do find staggering number of absentee fathers in the Bahamas and the reasons for this vary from voluntary abandonment, to involuntary separation (death, imprisonment, etc.). And in these cases women admirably lead the homes. You even find examples of this in homes with father-figures present. So there is this societal respect and love for mothering figures.

With that being said, I find the personal connection I have to these women in the exhibition allows for persons to more easily engage with the work. There is a global love and respect for mothers but not necessarily women.

The title Queen Mudda expresses the Caribbean vernacular. Can you tell us how conscious you were of adding African and Caribbean signifiers into your work to create the “language” of the show?

Caribbean signifies are always present in my work. Identity is huge theme for me and environment/culture greatly inform that. I always want a sense of place to be present in my work, even if I’m not illustrating a physical location.

The pieces nod to Rococo and Baroque aesthetics. Talk us through your choice for connecting the work to these style periods?

These style of works are associated with the gentry and the royals of society. I felt it was fitting to draw for these elaborate and opulent compositions when creating these elevating portraits of the women in my life.

It feels like art has been taken from people during lockdown. Do you feel like the Art world has suffered or adapted in the last 12 months? Where do you see things going as the world moves in and out of lockdown?

I feel like the Art world adapted as best as it could. The greatest struggle was seen in displaying the work. No matter how hard you try digital exhibition will not take the place of a physical one. However there were some great innovations, such as virtual studio visits, live artist talks and panel discussions. I was fortunate enough to be a part of a few during the pandemic and it was truly fantastic to be able to share and engage with persons on and international level from my studio.

Nonetheless I imagine that all of the technological structures that were introduced during the pandemic will remain, along with traditional offerings, as a way to increase the reach of these art spaces.