Revolutionary Artist and Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party.

About 1:

Emory Douglas was the first and only Revolutionary Artist and Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party. The party was founded in California in October 1966 and led by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale. Although famous for its militant stance, the Black Panther Party also ran a series of community programs including free breakfasts for school children. A counter-intelligence program led by the FBI resulted in the assassination, incarceration, and exile of party leaders, which further exacerbated growing divisions within the party. By 1980, one of the most significant left-wing parties in the USA was all but defunct.

Seize the Time, installation, 2012.

Seize the Time, installation, 2012.

About 2:

EMORY DOUGLAS (1943)

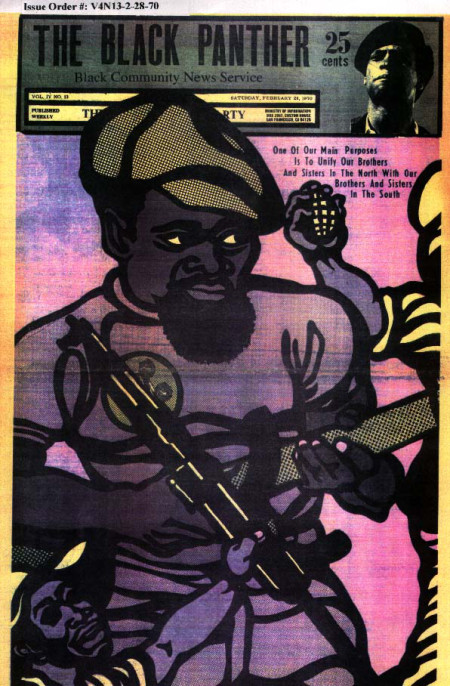

Black Panther’

Back Cover Book, 1971.

Back Cover Book, 1971.

James Baldwin wrote that “artists are here to disturb the peace.” He might have added that the artist’s job is also to create peace in the midst of disturbance. Both sides of the picture apply to the work of Emory Douglas, who from the late 1960s to the late ’70s was minister of culture in the Black Panther Party and its official revolutionary artist.

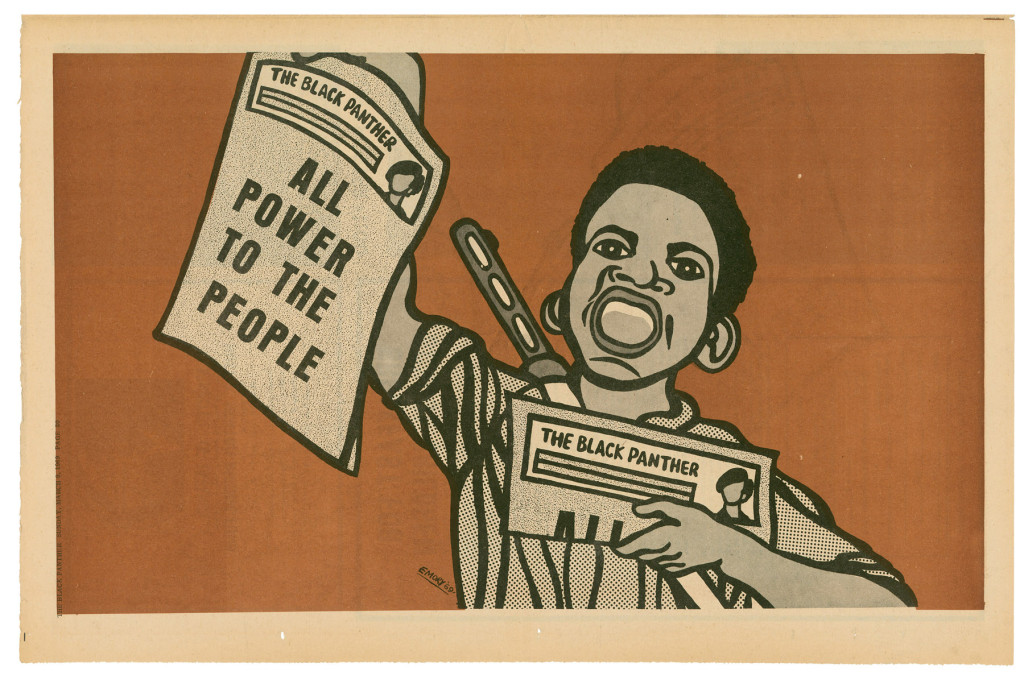

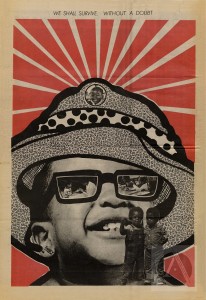

In these roles, he not only designed and illustrated the party’s weekly newspaper but also created a wide range of political posters, broadsides and promotional cards in a vigorously resourceful, eye-zapping graphic style. In 2007 a younger California artist-activist, Sam Durant, organized a survey of Mr. Douglas’s work for theMuseum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, and now that show, reconceived by Laura Hoptman and Amy Mackie, is at the New Museum.

Mr. Douglas joined the Black Panthers in 1967 after studying commercial art at City College of San Francisco. He began designing the newspaper with its second issue, and his illustrations for it were a direct response to the party’s early experiences of harassment and civic conflict. He invented the visual symbol of the porcine police officer that became a Black Panther signature. His 1960s drawings were done fast and loose, and they still carry the heat of the perilous events, the political ardors and the pressure-cooker deadlines that produced them.

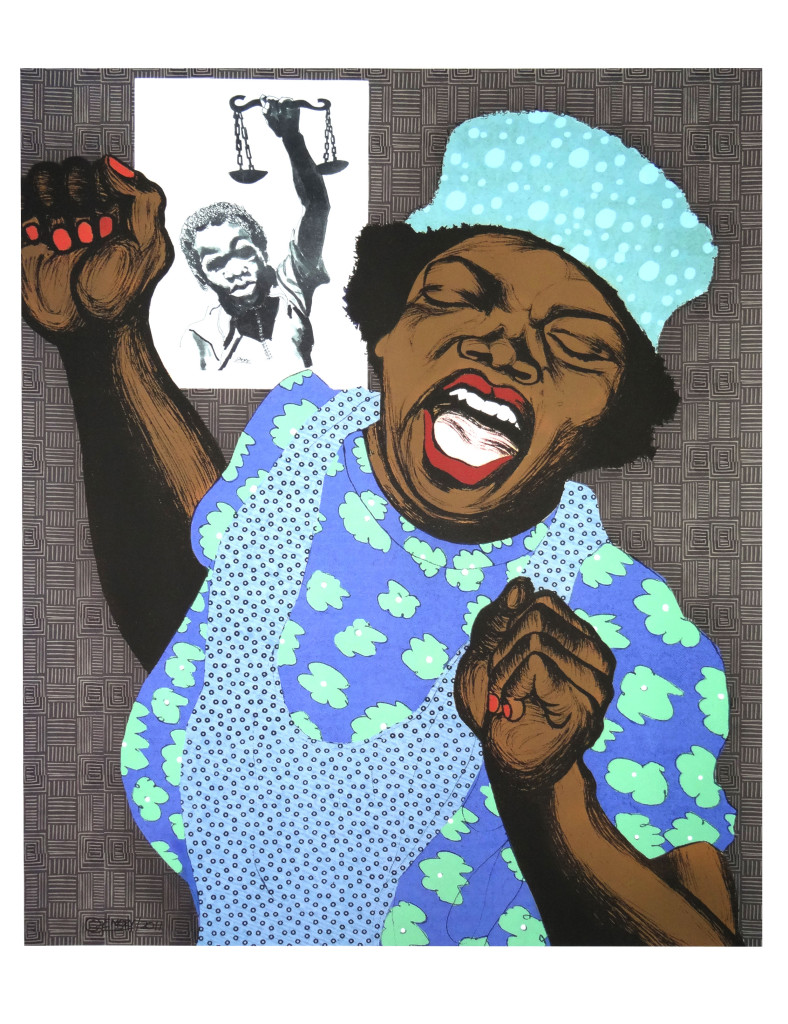

Later, as he turned to promoting the party’s social programs — providing free food and free clothing in black neighborhoods — his work become more deliberate and polished, with single, powerful figures drawn in thick black outline against a patterned ground, with terse captions placed above or below. Drawing on American art of the 1930s, contemporary cartooning and Socialist Realism from Cuba, Vietnam and elsewhere, his work was geared toward delivering unequivocal messages in forms that either jumped off the newspaper page or could be easily read from afar, taped in a window or pasted on a wall.

For Bobby Seale.

For Bobby Seale.

It’s hard to convey that kind of immediacy in a museum setting, where art almost automatically turns into artifact. And the New Museum compounds the difficulty by presenting Mr. Douglas’s work in reverential, precious-object terms, with newspapers and posters neatly arranged in a few vitrines sparsely distributed over a big space. The approach is classic white-box pure and a good example of how operating by the modernist letter can tamp down the art spirit.

But spirit comes through anyway. Mr. Douglas’s works were meant to be in your face and in your gut, and they are, irrepressibly. His early images are shockers and utterly appropriate, on-the-spot responses to a shocking time, when a group of disenfranchised citizens under assault was trying to carve out a pacific and protected place for itself.

(Holland Cotter on Emory Douglas, NYT, September 24, 2009)